In a move designed to establish a clear chain of command and create consistency across the vast city school system, Chancellor Carmen Fariña formally shifted power back to district superintendents Thursday and promised to disband the school-support networks that had eclipsed them.

The shake-up dismantles part of the Bloomberg administration’s system for managing schools, which freed them from some supervision but closely tracked their performance. But it also keeps parts of the system in place — most importantly, principal control of hiring and budgets — while creating new regional support centers like ones that were built and later scrapped under Bloomberg.

Under the new system, Fariña’s handpicked superintendents will continue to hire and evaluate principals. But now, it is also their job to get principals the help they need while ensuring they run their schools according to the city’s guidelines. The offices of the 45 superintendents will also answer to parents — offering them an outlet for concerns that many said was missing under the current structure.

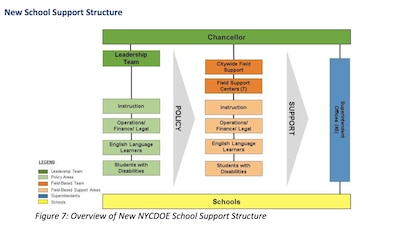

Under Bloomberg, schools chose to join one of roughly 55 support networks — multi-borough teams that helped schools manage everything from budgets and hiring to teacher training and curriculum. Now, Fariña will dissolve those networks and turn superintendents into schools’ main contact for both supervision and support. When schools need help with particular instructional or operational issues, superintendents will direct them to one of seven borough-based support centers.

Crucial details have yet to be worked out, such as who will staff the superintendents’ offices and support centers and how they will be funded. And it remains to be seen how principals who embraced the networks will adjust to the new system: While they retain authority over budgets and hiring, they will now face a level of oversight by empowered superintendents that they have avoided for years.

[More on what we don’t know yet about Fariña’s shake-up here.]

When she announced the restructuring Thursday, Fariña said she wants to create a more uniform and equitable support system, and also one that is streamlined and responsive to her demands.

“We are drawing clear lines of authority and holding everyone in the system accountable for student performance,” she said at a civic forum in Manhattan. “All of our offices – from central to the field – will be aligned under one vision.”

In the new system, the lines of communication all converge at the superintendents: They are the point people for principals and parents below them, and the education department leadership and chancellor above them. Their offices have been expanded from two or so staffers to six, whose roles will include helping respond to parents, evaluate principals, and manage struggling schools.

Fariña started laying the groundwork last year for this transfer of power back to superintendents. She made them reapply for their jobs and undergo training, and met with each one for an hour-long conversation. Now, as they take a much more active role guiding and instructing principals, Fariña will have a direct link to schools.

“They will be my eyes and ears,” she said Thursday.

When schools need assistance, superintendents will connect them with the new “borough field support centers,” which launch this summer. Brooklyn and Queens will get both get two centers, while the other boroughs will each have one. They will play the role that networks have, aiding schools with academic and operational matters, student services like healthcare and counseling, and support for students with special needs.

The education department is still working out the details of the centers, but officials said that some of their staffs will come from the networks, which have employed about 15 people each. In fact, some network staffers and leaders have already started taking new jobs within the department or in superintendents’ offices.

It is still unclear how big the seven new centers will be as they take on the role of nearly 60 networks. Schools currently pay for their networks’ service, but officials said they have not yet decided how the centers will be funded.

While most of the support networks will be abolished, a few run by nonprofits and universities will remain — though in a modified form. Groups like New Visions for Public Schools and Urban Assembly, which have founded and managed schools for years, will continue to support them. But superintendents will now monitor the performance of the groups, which will mainly offers schools instructional support, officials said.

“I view this superintendent as being a true partner,” said Richard Kahan, founder and CEO of the Urban Assembly, which includes 23 schools. “We’re going to be aiming for the exact same results using the exact same data.”

The school-governance shake-up is meant to address several drawbacks of the network system, Fariña said Thursday.

First, the multi-borough networks were often stretched thin and disconnected from their school’s communities and parents, Fariña said. Second, some served many more schools and students than others, yet they all had roughly the same amount of resources. Third, some paid too little attention to struggling schools. And finally, networks could offer principals advice, but they couldn’t force them to take it.

Now, parents and principals will both turn to superintendents, who are expected to know the their schools and communities intimately, Fariña said. By consolidating the network resources in the borough centers, they will be able to more robust and specialized support, she added. And superintendents, now in charge of supervision and support, will pay close attention to troubled schools.

Noah Gotbaum, an Upper West Side parent and member of the local community education council, said that many parents did not know the networks even existed, much less how to contact them.

“You needed a place to go,” he said. “And now we have that.”

After former Mayor Michael Bloomberg gained control of the school system, he tried to do away with the district superintendents completely, but was stopped by state law. So, instead, he kept them in charge of rating principals, but otherwise removed their authority. Besides those annual ratings and the support they sought from networks, principals were largely free from the regular oversight of a supervisor able to force changes.

“The new chancellor believes, correctly, that principals need some supervision,” said Clara Hemphill, the founding editor of Insideschools at the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs, who has written about Bloomberg-era school governance. “The question is whether the superintendents will be good supervisors.”

It remains to be seen how principals who favored the network system will respond to the changes. After Mayor Bill de Blasio was elected, about 120 principals lobbied him to let them keep their networks.

They said the networks’ non-geographic nature helped counter the city’s racial and economic segregation by letting educators from different neighborhoods meet up for trainings. And the fact that networks did not rate principals made them comfortable asking the networks for whatever help they needed, the school leaders said.

“We are deeply committed to our networks,” the principals wrote in late 2013, “and do not want ours to be dismantled because some are not working well for others.”