Michelle Varuzza, an 11th and 12th-grade math teacher at Queens Metropolitan High School, sat on the edge of a student desk after school last week and prepared her colleagues for what they were about to see.

“It’s one of the first lessons of trigonometry, and they’re pretty scared of trigonometry to begin with,” she said in the no-nonsense tone familiar to her students. “So it’s kind of like pulling teeth a little bit.”

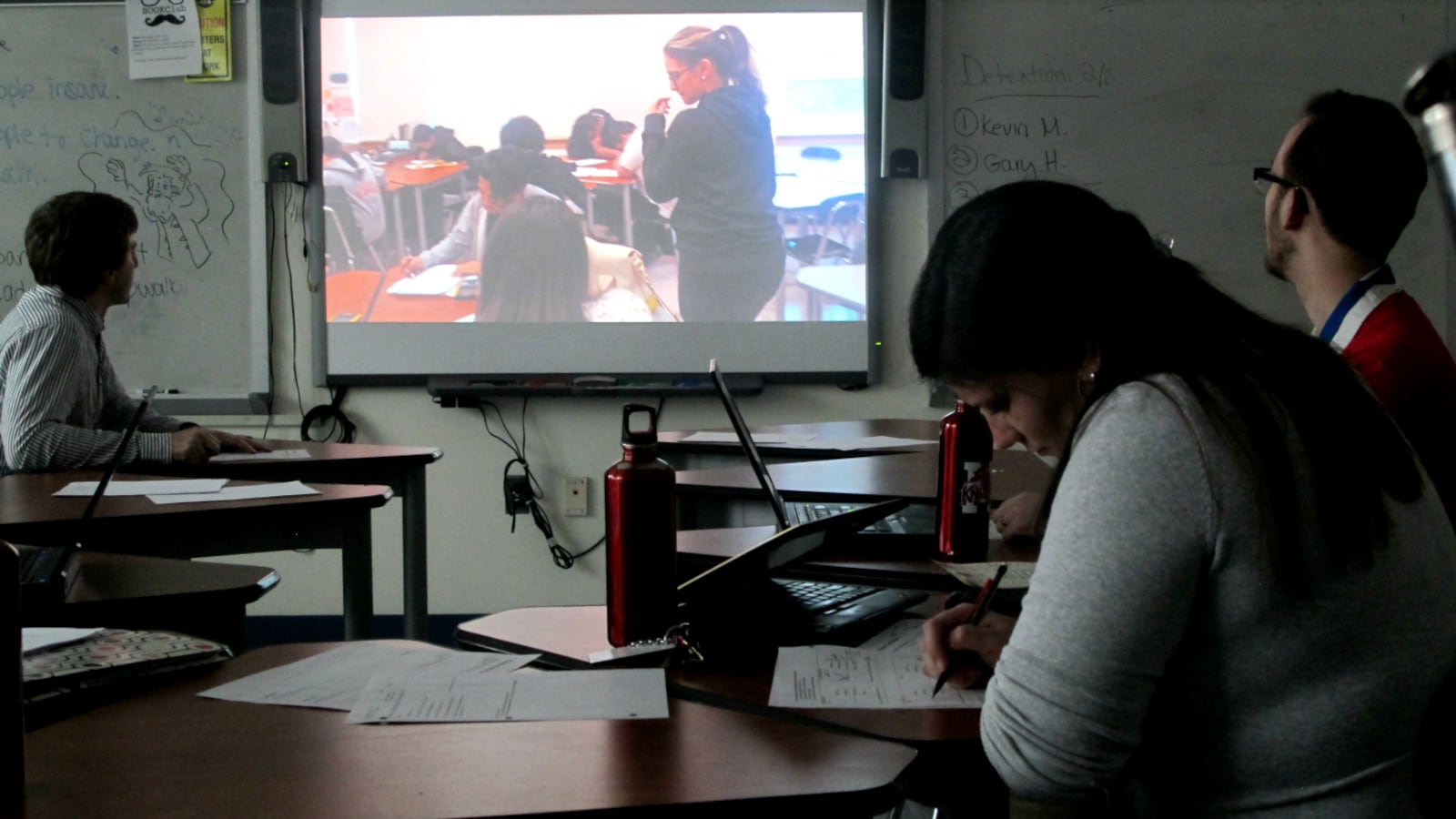

Varuzza and five other teachers (three math and two English) were there for a weekly “video club,” where teachers watch a recording of a colleague’s lesson and give feedback. They meet every Monday afternoon during mandatory “professional work” sessions at their school.

Since a state teacher-evaluation law went into effect in the city last year, the teachers have gotten used to being observed and rated more often by administrators. But to the educators at Queens Metropolitan, who started the video club last spring, classroom feedback is most helpful when it’s from teacher to teacher with no ratings attached.

“If you’re there for evaluative purposes, people kind of shut down for feedback,” said ninth-grade English teacher Chris Fazio, who had recorded Varuzza’s lesson earlier that day on his iPhone. “This is an alternative to that, where there are zero stakes.”

The club isn’t centered on any one strategy or subject area, which is why teachers from across grades and departments are invited — a rarity in many high schools. That’s also why 10th-grade English teacher Ramsey Ess said to Varuzza before the video started, “I have an embarrassing question: Trig covers what?”

After Varuzza explained that the lesson was an introduction to reference angles, which are used in trigonometry to calculate the function values of other angles, she left the room and the video started. (The club asks observed teachers to leave while the others watch the video so they aren’t tempted to explain their actions.)

In the video, Varuzza briskly demonstrated how to find the angles, then led the class through practice problems. The camera followed her as if she were the star of a reality-TV show, panning from her at the board to students quietly taking notes and trailing her when she zigzagged between their desks.

The teachers in the club jotted down notes as they watched the video on the classroom’s electronic whiteboard. After 10 minutes, Fazio stopped the video and asked the teachers to translate their observations into “warm” and “cool” feedback.

“Warm feedback being the things that Michelle’s doing well that if she did more of she’d get a lot more out of the class,” Fazio explained to the teachers, “and the cool feedback being opportunities for her to improve.”

Before the club existed, educators at the school got reviews of their teaching in a couple ways: Through the new evaluation system, and when teachers occasionally observe colleagues in their departments. The club, however, was meant to address shortcomings with both of those systems.

The video recordings can be stopped and replayed in a way that live observations cannot and, unlike the peer visits, no administrators are present when teachers share their feedback. (Principal Gregory Dutton said in an interview, “I know nothing about what’s going on in the teacher video club.”) In contrast to the evaluations, feedback in the club does not include scores and it comes from fellow teachers, who know firsthand how hard it can be to pull off a great lesson.

“There’s no gotcha mentality here,” said 10th and 11th-grade math teacher Katie Anskat.

After the teachers wrote down their thoughts that afternoon, they shared them aloud while Fazio transcribed their comments in a document for Varuzza to see when she returned.

For the warm reviews, they agreed that Varuzza clearly explained complicated topics and that she moved her class seamlessly from demonstration to practice problems — though the English teachers suggested that she give different parts of her lessons labels, like “stop and jot” or “turn and talk,” the way they do.

“You English people come up with such fancy names,” said Nicole Coqueran, a 9th-grade math teacher.

For their cold feedback, they suggested that Varuzza ask more open-ended questions so that students grapple with the theories behind the procedures, and that she get students to help explain the concepts to one another. For each recommendation, they cited the relevant part of a rubric that teachers are rated on in the evaluation system, and they gave a timeframe — either two weeks or two months — for her to try to make the changes.

When Varuzza came back in the room, they shared their advice with her and she thanked them. After the club, she said her colleagues’ observations are often more helpful than administrators’, who sometimes seem to fixate on matters outside of her control.

“We’re here to focus on the teacher as an instructor,” she said, “not whether four students walked in late.”

The club is looking to recruit more members, said English teacher Heather DeFlorio Asciolla, who created it last year with history teacher Frank Swetten at the suggestion of their school-support network, CFN 403. Some teachers are deterred, however, because the evaluation system has convinced them that “whenever someone observes you, there’s a rating attached,” she said.

But the club can be a powerful tool for those who participate, she added. Last year, 95 percent of her students passed her class, compared to 81 percent the year before the club started.

“I truly believe,” she said, “it’s because my colleagues looked at my instruction, gave me ideas, and I took it back to the classroom.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story said teacher Heather DeFlorio Asciolla referred to an increase in students passing a Regents exam, not her English class.