After a turbulent year at Boys and Girls High School that was marked by a high-profile leadership change and intense official scrutiny, Mayor Bill de Blasio told this year’s graduates on Thursday that their accomplishment represented a “rebirth” for one of the city’s most troubled schools.

Ninety-three Boys and Girls students graduated on Thursday, double the number expected to earn diplomas at the start of the year, de Blasio said. But even as he celebrated their accomplishments and commended the school’s new principal, Michael Wiltshire, urgent questions hung over the school, including whether it could reverse its steadily declining enrollment and how it will continue to raise its strikingly low graduation rate.

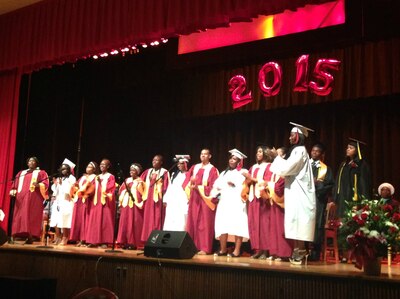

“I want you to know the eyes of the city are on you,” de Blasio said at the school’s graduation ceremony Thursday, where the girls wore white caps and gowns and the boys wore red. As if to prove his point, two opposing education advocacy groups sent out dueling statements Thursday after de Blasio’s speech to either praise or condemn the city’s efforts to rehabilitate Boys and Girls.

After the school’s outspoken principal left the school in October after publicly clashing with the city over its improvement plan for the school, Wiltshire agreed to take over. The city wooed him there with a bonus and a new title that let him keep oversight of the high-performing Brooklyn high school he’s run for many years, Medgar Evers College Preparatory School.

He faced a formidable challenge at Boys and Girls. The school had a 42 percent graduation rate last year — 26 points below the city average and 10 points under the average of schools in de Blasio’s “Renewal” improvement program, which includes Boys and Girls. It had gone so long without making gains or enacting a turnaround plan that it was one of just two schools last year to earn the state’s “out of time” label, forcing the city to make drastic changes that included requiring all staffers to reapply for their jobs.

Wiltshire moved quickly. He added an extra period to the school day so students could take more classes, and hired Kaplan to offer test preparation courses. Since Boys and Girls offered few advanced classes, he let top students take classes at Medgar Evers (“I was not with you for most of my senior year — I was at Medgar,” salutatorian Oliver Gaussaint said in his speech Thursday). He also raised expectations for both the students and staff, telling athletes they had to “pass to play” and ordering struggling students to attend tutoring, several students said Thursday after graduation.

“He made us strive harder,” said graduate Gail Romain, adding Wiltshire’s higher expectations also rubbed off on teachers. “The approach everyone had toward us was different — everyone strived harder for us to be the best we can be more than they normally did.”

Considering the state’s closure warning, Wiltshire entered the school with a mandate to make rapid gains.

One of his first actions was to encourage about 30 students who were significantly behind academically to transfer to schools designed to catch them up. (Overall, the school shed nearly 100 students this year, with its enrollment falling from an adjusted 580 students in October to 487 today, officials said.) Some students and staffers said Thursday that those students could not have graduated without the help of an alternative high school program, but others said that struggling students were urged to leave even if they could have caught up at Boys and Girls with extra help.

Sherried Velez said a staffer called her after Wiltshire’s arrival and urged her to sign off on a transfer for her son, David Lewis, who was 20 years old and needed to pass several Regents exams this year to graduate. She declined and he remained at Boys and Girls, where he got tutoring and was able to earn a less rigorous “local” diploma, she said. (The state has eliminated the local diploma option for students who entered high school more recently.)

“If you fought back,” she said after Thursday’s ceremony, “they couldn’t push your child out.”

Wiltshire and an education department spokesperson did not immediately respond to requests to comment on the incident. However, Assistant Principal Andrea Toussaint said that, in general, students who were encouraged to transfer were sent to programs where “they got exactly what they needed.” She pointed to one student who transferred to an alternative program, where he was able to graduate this month and secure a full scholarship to a community college.

The administration also apparently went to great lengths to help get students to graduation. Two staff members said they were told students had until June 24 — one day before graduation, and after teachers had entered final grades — to make up work in order to pass classes they were in danger of failing.

Other questions loom over the school’s coming year.

One is whether it will be able to attract enough new students to stay afloat, a major challenge for a school whose enrollment plummeted from 2,300 in 2010 to under 500 today. Officials said applications are up, with 154 students applying this year compared to 97 last. But a teacher said only 65 freshmen have enrolled so far.

Another question is who will work at the school. Under state pressure, the city and teachers union agreed to a rehiring plan that required all Boys and Girls employees to reapply for their positions if they wanted to work at the school next year. Those who are not rehired by the committee, which includes city and union representatives, will be sent to other Brooklyn high schools with job openings. Some staffers said Thursday they had not yet been notified about the committee’s decision, but expected to by Friday, the last day of the school year.

After the mayor spoke at Boys and Girls’ graduation ceremony, valedictorian Salomon Djakpa gave his speech. After arriving in the U.S. from Senegal his freshman year, Salomon went on to earn a 94.29 grade-point average, to play varsity soccer and volleyball, and finally to win a full scholarship to Cornell University.

“My family and I migrated to the United States approximately four years ago in search of a dream,” he told the audience. “I took with me the shirt on my back, the fire in my belly.”