Jason Rosenbaum knew his high school had a problem: Students often arrived years behind in reading and the school struggled to get them to graduation. He tried tweaking the curriculum, but not much changed.

So when New York City’s education department required Juan Morel Campos Secondary School to adopt a new curriculum last year as part of its high-profile “Renewal” turnaround program, Rosenbaum jumped at the chance to quickly change things up.

“Looking back, I was standing at the edge of this cliff and I’m glad someone pushed me,” he said. “Maybe I was moving too gently for what our kids needed.”

Like the other 93 low-performing schools in the city’s program, Campos Secondary School is getting access to health care services, after-school activities, and other help as the city tries to turn it into a hub of social services. But at many schools, equally significant — but less visible — changes are happening behind classroom doors, as educators try new techniques for reaching struggling students.

At Campos, a key part of that change is the new high school English curriculum. It asks students to dig into more complicated texts, performing “close readings” that sometimes take weeks. And it has the whole high school English department starting with the same game plan, even though most teachers have been used to a lot of autonomy.

“English teachers, traditionally — we haven’t had curriculum,” said Peter Seidman, a consultant the school hired to help teachers adapt to the new EngageNY coursework. “They taught the texts that they were familiar with and in the style that they had been taught growing up. And so it becomes very difficult to ensure rigor and ensure consistent high expectations.”

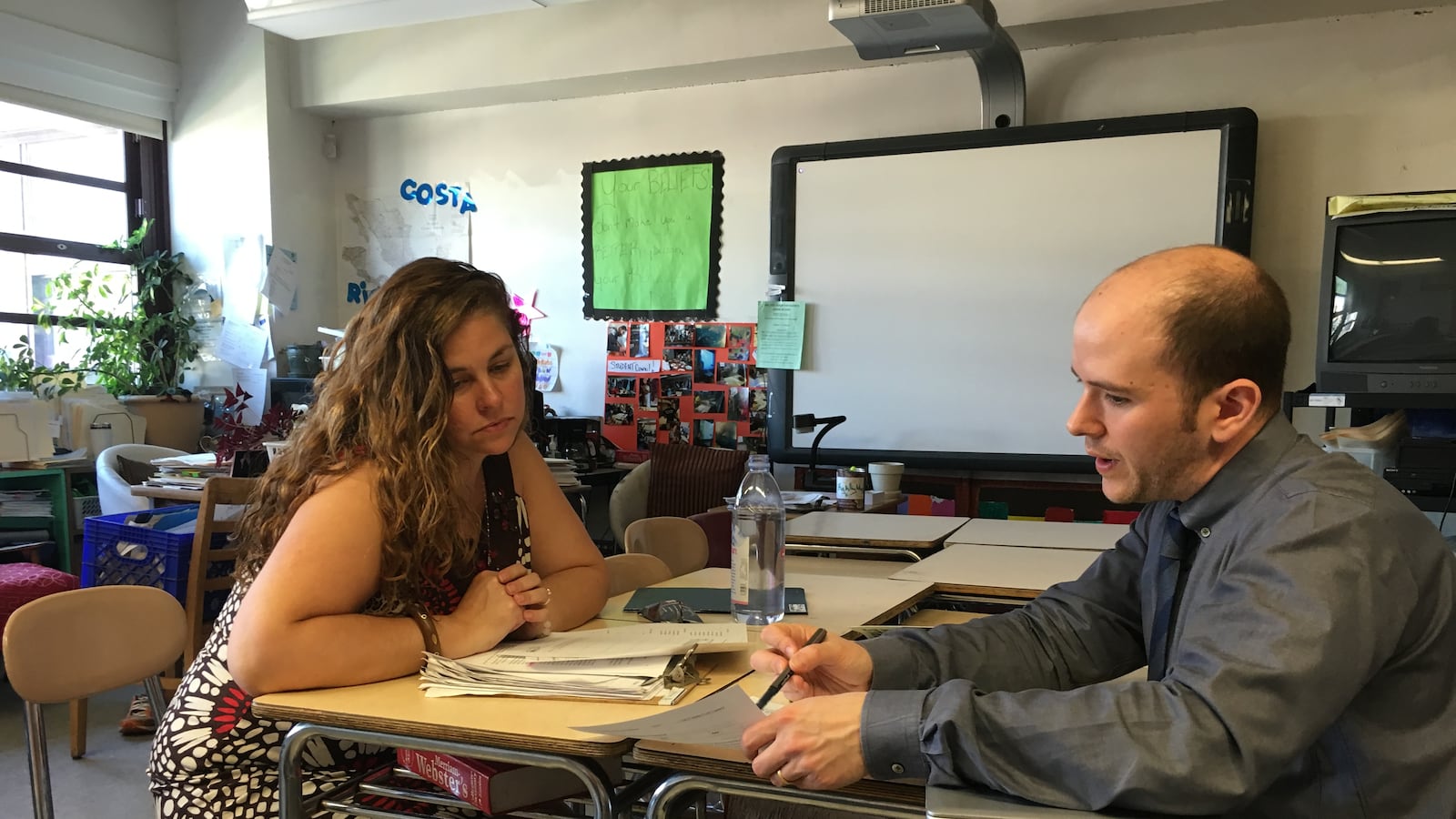

Over the past school year, Seidman has dropped into classrooms to offer feedback, help develop lesson plans, and troubleshoot problems. He says he wants to be a sounding board for teachers, not a critic.

“The teacher needs to understand that you’re on their side and that you’re not an evaluator,” explained Seidman, who works for Public Consulting Group, the education firm that designed the new curriculum.

Education department officials noted that many schools in the turnaround program are using their extra resources to hire coaches to improve instruction, and help teachers adapt to Common Core standards.

The stakes are high for the Williamsburg, Brooklyn school, which is spending $30,000 on the extra support. Just 48 percent of students graduated on time in 2015.

And though teachers and school leaders say the new curriculum is starting to take hold, the process has required winning over some skeptics.

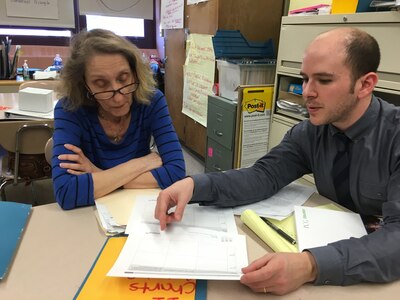

Pat Sirulnick, a 12-year veteran of the school, had her doubts. Many of the school’s students are two to four years behind in reading, one-third have disabilities, and a quarter are English language learners – and she worried they would disengage.

“Our students don’t have the best retention and interest level,” Sirulnick said. “These were challenging texts – I was concerned that they would get bored and really antsy.”

On a recent Monday, though, Sirulnick sat down with Seidman to review two writing samples from a student who is both an English language learner and has a disability. They noticed that the student’s comparison of the Atlanta Compromise and W.E.B. Du Bois’ “Souls of Black Folk” was more sophisticated than a writing exercise from eight months earlier.

Sirulnick said it’s hard to know how much to attribute those gains to the new curriculum, but after using it for just a few months, she has been surprised that students haven’t given up on the more painstaking approach.

“I don’t know why they weren’t bored, but they weren’t,” she said of the close reading.

Seidman has worked with teachers to adapt the work for the school’s highest-needs students. Students may read a graphic novel version of a text like “Romeo and Juliet,” for example, and look at smaller sections of the original where appropriate. Another student, who is in danger of dropping out, was recently allowed to explore a research topic that didn’t relate to the text that his class was reading in an effort to keep him engaged.

That flexibility, and the school’s slow adoption of the changes over the course of the school year, has made it easier to get faculty members on board, Rosenbaum said.

“Any change is hard because it means letting something go, and teachers understandably become wed to things that they believe truly help our students,” he said. “I was surprised at how quickly they recognized the value.”