In Evelyn Rebollar’s classroom, a student is listening to music on his phone while typing away on a laptop. Behind him, a classmate is fiddling with a deck of cards. One student is playing the computer game Age of Empires in the back corner. A couple tables away, one of his peers is chatting with another teacher in French.

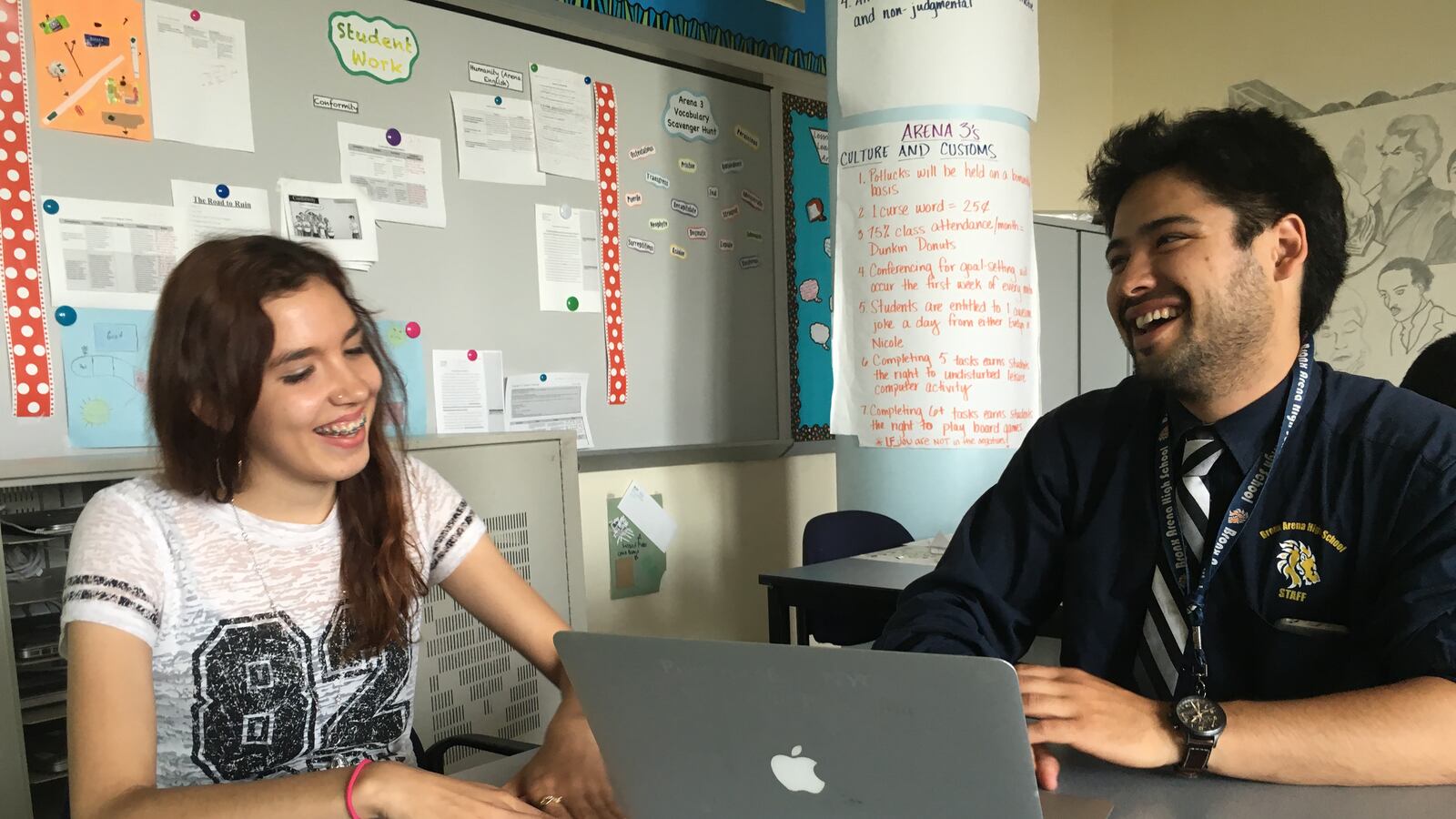

Rebollar is sitting at the front of the room, though the tables are arranged so most students aren’t facing her. The setup might seem strange: All of these students are in the same class, but at this moment, none of them are on the same task. Rebollar occasionally paces through the room to check in on her students, but she isn’t bothered if a phone is out, or if one of them is momentarily distracted.

“We try to make the model as close to what they’ll experience in the work or college environment,” Rebollar explained. “Your boss isn’t going to say, ‘Why are you on your phone?’ They’re going to say, ‘If you don’t complete this project, you’re fired.’”

Opened in 2011, Bronx Arena is one of about 52 “transfer” schools across the city that often innovate to serve students who have dropped out or fallen behind their peers. For Bronx Arena, that means turning traditional teaching on its head.

Instead of shuttling between hour-long classes, students spend roughly four hours a day in their “arenas” — groups of 25 students who work their way through a self-guided online curriculum that is individually tailored to make sure each student develops the core “competencies” needed to graduate.

By discarding the convention that teachers should spend most of their days delivering content from the front of the classroom, teachers at Bronx Arena are freed up to teach small mini-lessons and work with individual students on developing — and reaching — their own learning goals.

That freedom is the key to re-engaging students who are all at least 16 years old and behind in credits when they enter Bronx Arena, explained Ty Cesene, one of the school’s co-principals. The idea is to give students ownership over what they’re learning by letting them participate in choosing their coursework and managing their time during the school day.

“The students have so much choice and power over what they’re doing on a day-to-day basis,” Cesene said. “We wanted to provide a full new experience so you had to adjust your idea of school.”

But the model can also be an adjustment for teachers, who must closely monitor student progress on each of their courses to determine whether they are meeting the monthly academic goals they’ve agreed to, and if they’re completing at least five daily assignments – all of which is measured with elaborate tracking software.

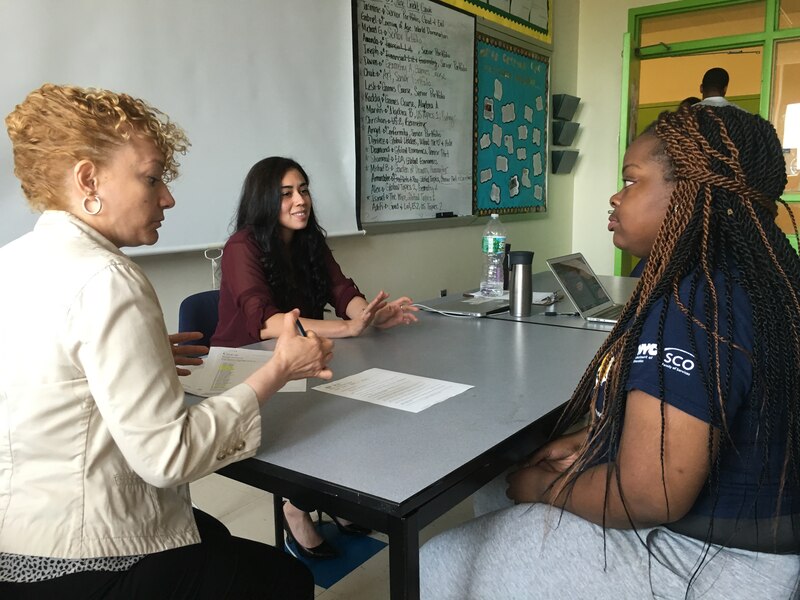

And even though specialists in subject areas like French and Earth science drop by the classroom to help individual students, teachers who supervise an arena must also be prepared to oversee students who are working on subjects in which the teacher hasn’t been formally trained.

“I had to learn humility and sort of be okay with showing my weaknesses,” said Rebollar, whose expertise is in English instruction. “If you are a generalist teacher, inevitably there will be answers you don’t know. It’s a mindset of problem-solving.”

Rebollar — who recently won a national TNTP Fishman Prize for quality teaching in high-need schools — paced around her arena one afternoon last month checking in on each student’s progress.

The student who was playing with a deck of cards, for instance, is working on a class that explores the theme “coming of age” and requires designing a board game to illustrate the concept. Rebollar helped her get started by pushing her to experiment with altering the rules of a card game and playing it with two other students to better understand how games are structured.

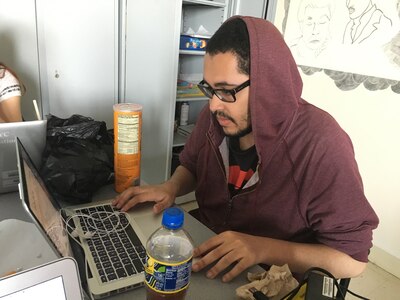

Another student, Amanda Lopez, asked about how to organize a presentation of her senior project, which focuses on the presidential candidates’ views on abortion. And the student who was playing Age of Empires? That’s Michael Gastambides, a 20-year-old whose senior project uses the game to compare monarchies to democratic republics.

Like many of the roughly 200 students at Bronx Arena, Gastambides felt disengaged and unhappy at his last high school, which was about seven times larger. “I kind of developed anxiety, I was claustrophobic, and I just stopped going,” he said of his last school. “I wanted an education, I wanted a diploma, I wanted to go to college, so I came here.”

Gastambides graduated this year, but he acknowledges that the self-paced aspect of his high school experience wasn’t always easy. “I would be lying if I didn’t say sometimes it is hard to get motivated,” he said. “The teachers, they motivate you — they come in and they say, ‘You can do this.’”

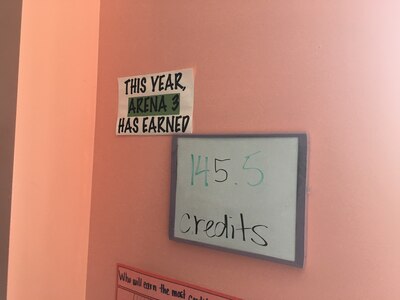

But getting students to graduation isn’t always easy. School leaders acknowledged Bronx Arena lags behind some of its peers in getting students to quickly accumulate credits, and has struggled with an attendance rate that hovers around 60 percent.

Cesene pointed out that even if students aren’t earning credits as quickly, that’s because the school requires students achieve proficiency in all elements of their coursework before they move on. And to boost attendance, the school has worked with its community organization partner, SCO Family of Services, which provides “advocate counselors” who make calls home and even visit if a student is chronically absent.

Since the curriculum is largely self-paced, “If you miss a day, you didn’t miss the class,” Cesene said. “It’s a double-edged sword to have a model that doesn’t punish not attending.”

Still, the school’s model has earned some attention from those outside its walls. “The co-founders are constantly challenging the assumptions, rituals and routine of the traditional school model,” said Chris Sturgis, co-founder of Competency Works, an organization that disseminates information about efforts across the country to re-think what it means for students to master coursework, and who visited the school two years ago.

And while Cesene acknowledges that the school will continue to tweak the program, at least one thing will stay constant. “Our language here is you’re responsible for your education,“ he said. “Our biggest innovation is we trust students to learn.”