Students taking high-stakes tests often try to control as much as they can, down to what they eat for breakfast and even the pencil they use.

But they can’t control the temperature outside — and that can make a big difference, according to a new study that looked at the impact of heat stress on exam performance in New York City.

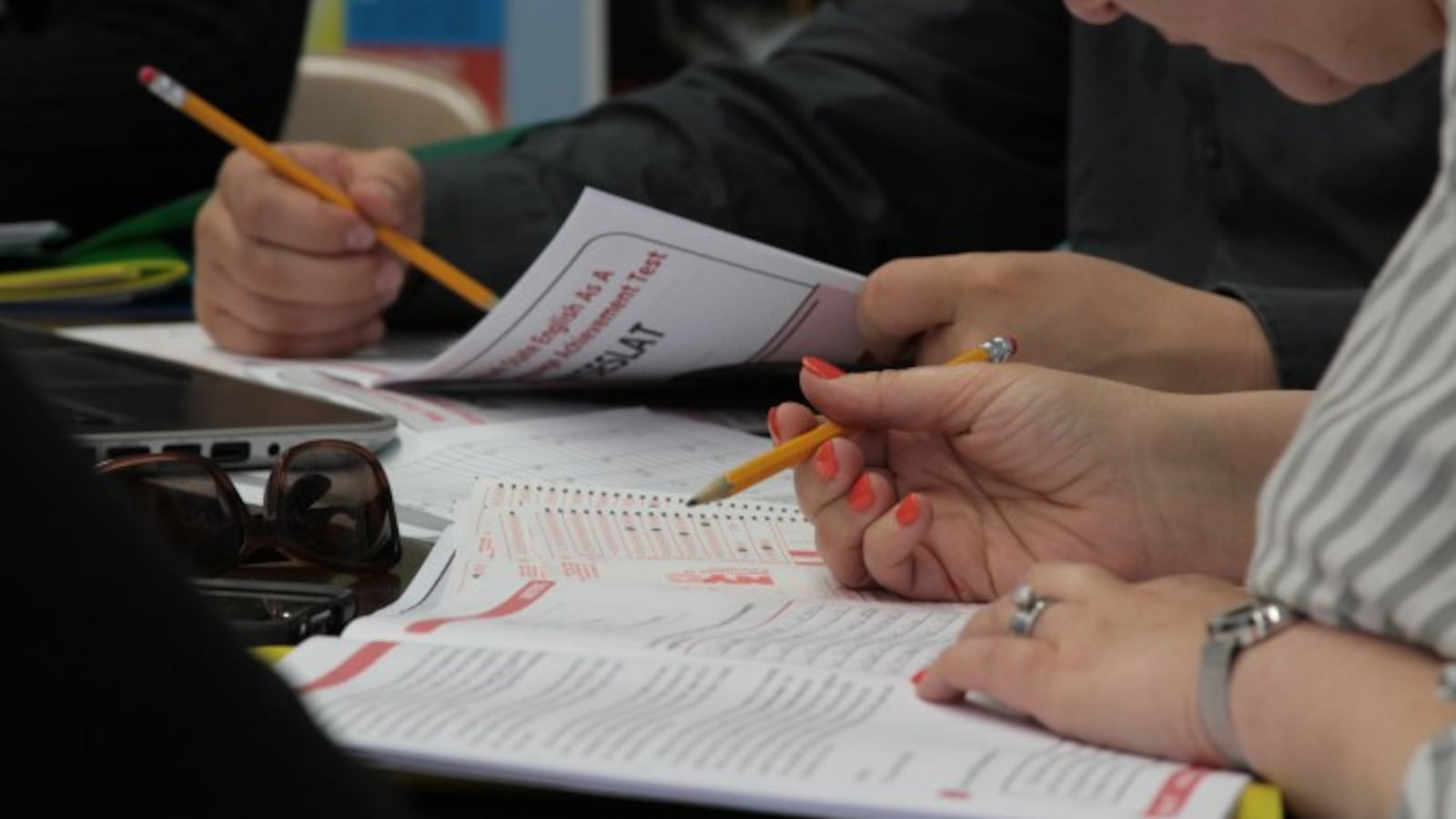

The study, a working paper by a Harvard University graduate student named Jisung Park, focused on Regents exams, the tests that students must pass to graduate from high school in New York. Most of those tests are taken in mid-June, when it can be temperate in the city — or sweltering.

Looking at 4.5 million exams taken by nearly 1 million students over 13 years, Park concluded that students are almost 11 percent more likely to fail an exam on a 90-degree day than on a 72-degree day.

“I find that acute heat stress during high stakes exams reduces the likelihood that a student graduates from high school on time,” he writes. High temperatures in the weeks leading up to the tests can also take a toll, he concludes.

Park is an economist looking at the impact of climate change, and he concludes that hotter days, which are becoming more frequent and lasting for more of the school year, might hurt students’ long-term outcomes.

One reason: The difference between a 90- and 72-degree day erases nearly three quarters of the impact of a highly effective teacher, as calculated by a seminal 2012 study that found that students with effective teachers earn more over their lifetimes.

High temperatures also have an impact one quarter the size of the black-white achievement gap, according to Park, who writes that the issue has never before been examined.

Park concludes that air conditioning schools could boost student performance — an argument that many, including advocates in Denver who want voters to pay to cool schools, have made. But the difference is small, which other researchers have speculated could be because AC units are loud and can reduce air quality.

A high proportion of New York City students, and an even higher proportion of poor students of color, score right around the passing threshold of 65 points. Park found evidence that when teachers scored their own students’ exams, they compensated for the heat and inflated scores for students on the brink more the hotter it got. He calls this a “hitherto undocumented (likely sub-optimal) channel of climate adaptation.”

That channel disappeared in 2011, when the city cracked down on score inflation by sending exams to centralized grading centers. Scores fell across the city. Park writes: “A possible unintended consequence of eliminating teacher discretion may have been to expose more low-performing students to climate-related human capital impacts, eliminating a protection that applied predominantly to low-achieving black and Hispanic students.”