It’s 5 p.m. and the open house for prospective students at Pace High School in Chinatown is just getting underway. As students arrive, they are handed a clipboard with a survey.

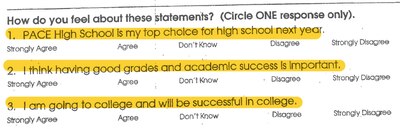

They scribble away for the first 20 minutes or so, explaining the struggles they have overcome and which components of Pace they like. They indicate whether Pace is their top-choice school, if academic success is important to them, and whether they want to go to college.

“It is very, very important that we get the surveys back from you, as they are the attendance for this open house this evening,” says Michael Sowiski, an assistant principal at the school. “It does have an impact on the admissions process.”

Yet Pace is what’s known as a “limited unscreened” school, which means its students are selected by random lottery. Even though it has dozens of applicants per seat, it can grant priority status only to those who attend an open house or visit the school’s table at a high school fair.

Sowiski said the students’ answers aren’t used in the admissions process. Yet the very existence of the survey raises questions about whether the city’s rules for admission to limited unscreened schools are vulnerable to abuse.

Several schools, including Pace, seek information about students above and beyond what they actually need — but it’s unclear why. They may want to discern which applicants truly want to attend the school, which can be difficult under the current rules, or to target high-performing students for recruitment. Or maybe they’re just curious to learn more about who’s applying.

But one thing is certain: Collecting extra information gives schools a tool to filter their applicants, and the Department of Education does little to ensure they don’t.

It’s no surprise that the schools would push the boundaries. The entire structure of the high school admissions system, which allows scores of schools to screen applicants and pools most of the lower-performing students in unscreened schools, creates the temptation.

“Every high school figures out some way to limit their population,” said Eric Nadelstern, who worked in the Bloomberg administration when officials created the “limited unscreened” designation and is now a professor at Teachers College.

“I don’t think the solution is, let’s root out corruption where it exists,” he said. “It’s endemic.”

***

When the city introduced a universal lottery system in 2004, the idea was to give students access to a wider range of high schools. There are roughly 150 high schools with a “screened” program that weighs applicants’ academic history, and around 230 schools with a “limited unscreened” program that weighs only students’ interest in attending. After students rank their choices, the unscreened schools receive a list of applicants and mark which ones attended an open house or high school fair.

But the system isn’t working. As Chalkbeat has reported, open houses are often poorly advertised, far from families’ homes, and can be held during weekdays — creating a burden for all students, and particularly for many low-income families. And many schools are already not following the rules of granting priority at the citywide high school fair.

Since schools are the sole keepers of information about which students should get priority, there is nothing to guard against them tinkering with their lists. They could leave off some students who have demonstrated interest, for instance, or grant priority only to those they especially want.

And some say that with the survey that Pace distributed, for example, it’s hard to imagine anything other than that happening.

“They’re really not supposed to be doing that,” said Sean Corcoran, a researcher at NYU who has studied the high school admissions system, regarding Pace’s survey. “There’s no other reason to use that except for screening students.”

Raymond Johnson, the parent coordinator at the Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice in Brooklyn until 2011, said his school also distributed a short survey at open houses. And based on students’ responses, Johnson said, they might be included or excluded from the school’s priority list. Though he was not in the room while those decisions were being made, he said, he was close enough to the process to hear it being discussed.

“It was definitely something that was talked about,” Johnson said. “It was definitely something that many people knew about, and that was the way that they were able to recruit a lot of potential students.”

To his knowledge, the practice was widespread. “That was the norm,” he said. “But it wasn’t something that was promoted. Clearly, it was something that was done behind closed doors.”

The current principal of Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice, Suzette Dyer, said the school still collects information about students, but it plays no role in admissions.

“We ask students to provide us information about themselves as well: what middle school they attend, how to reach them, and what they and their parents hope to find in a high school,” Dyer said in an email. “This information does not impact their ranking at all. Instead, it is used for us to begin creating a strong partnership between the school and the students and their families once they’ve been matched to our high school.”

But even if the surveys are not used in admissions, Corcoran said, just distributing them could discourage families and students from applying to the school.

“You’re there to find out more about the school and then basically they’re putting an assignment in front of you,” Corcoran said. “That can be a real turnoff, and a student may just decide a school is not for them if they didn’t feel confident about crafting an essay.”

Sometimes, the interest form asks a question that city officials said is discouraged: Is this school your top choice? The current lottery algorithm was designed to incentivize students to rank schools in their actual order of preference, rather than limiting their top choices to the schools most likely to accept them. Some schools tell students the system gives preference to applicants who rank them first on their lottery list, even though that is not the case.

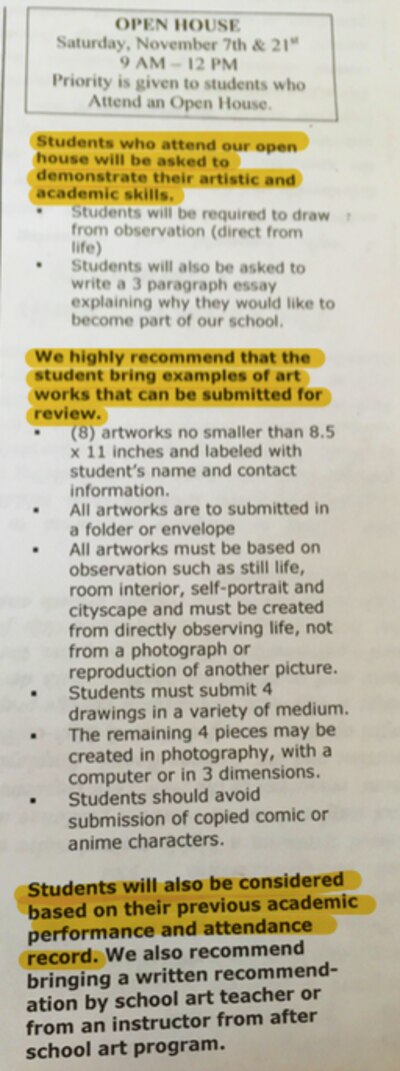

Other schools ask students to complete certain activities. At Bronx High School for Visual Arts, ninth- and 10th-grade counselor Sasha Santiago said students are asked to complete an art demonstration, which involves drawing a still-life picture, and answer a couple of questions about themselves at the open house.

Santiago said the quality of the artwork and the students’ answers on the questionnaire are not used in admissions.

“We’re a limited unscreened school, point blank, period. Nothing has changed,” Santiago said.

According to the Department of Education, schools are allowed to collect surveys or ask students to complete activities, as long as they don’t factor those responses into admissions decisions. But it is nearly impossible to know whether schools are following those rules, since the DOE allows them to operate on the honor system — allowing the schools themselves to mark who gets priority.

“We’ve taken concrete steps to improve the high school admissions process and we recognize it can be challenging for families,” said education department spokeswoman Devora Kaye. “We continue to review this process in our work to ensure all students and families have access to a high-quality school.”

***

Limited unscreened schools are permitted to recruit students, but they are barred from considering students’ grades, test scores, or attendance records in admissions. But there’s still plenty of gray area in the rules — and schools may not abide by them in the first place.

At the citywide high school fair, Cecily Zayas, parent coordinator at the Urban Assembly School of Music and Art said her school does “not only look at who comes to an open house.” The school examines three years’ worth of attendance and looks at student grades, she said, though it does not make “harsh” decisions based on a student’s GPA. Her principal, she explained, wants to make sure students are a good match for the school.

“A lot of schools tend not to [consider attendance and grades], but my principal does to figure out who would be a good fit for our school,” Zayas said.

That school’s principal, Paul Thompson, said Zayas “misspoke and does not have access to any student information around admissions and has a misunderstanding of the process.” Afterwards, Zayas herself also sent an email saying she “unintentionally misrepresented” her school’s enrollment policies at the fair. But it’s worth noting that information was disseminated to parents and students, since she was the one manning the school’s table for at least a portion of the day.

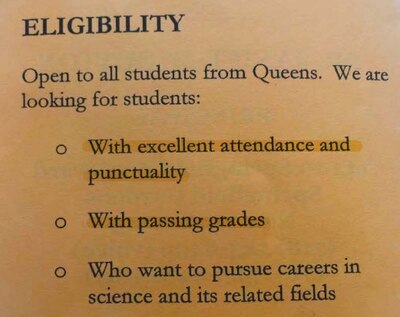

Also at the fair, representatives from George Washington Carver High School for the Sciences, a school in Queens, handed out a brochure with an “eligibility” section, stating that the school is looking for students with “excellent” attendance and passing grades.

Again, it’s hard to know if the schools are actually screening — and to what extent. Principal Janice Sutton said they only look at the “eligibility” requirements listed in the brochure after students have been admitted.

But students working the table at the high school fair thought the opposite. Chyanne Blakey and Darshan Boyce, both 11th-graders at G.W. Carver, said they thought students had to have a 75 average to be accepted at the school, and that students had a better chance of getting in if they had good attendance and participated in science clubs.

A counselor at a high school in the Bronx, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that while schools can’t explicitly collect information on students, middle school and high school guidance counselors talk all the time and may informally share information about students’ grades or disciplinary history.

“If you have a source, they can kind of give you some information,” he said.

Several schools at the citywide fair peppered their sign-in sheets with stars next to certain students’ names to indicate an applicant very interested in the school, for instance, or one with a relative at the school.

It’s unclear how schools use those stars to recruit students, but Zoraida Torres-Rodriguez, the parent coordinator at Bronx School of Law and Finance, said she will do “anything” to convince one of those students to come to the school, including knocking on his or her door.

***

It’s no wonder that “limited unscreened” schools feel pressure to attract the students most likely to succeed. The structure of New York City’s high school admissions system means that most of the highest-performing students are funneled into “screened” and specialized schools, which can select students based on grades, attendance, interviews or tests.

A new report from the Independent Budget Office found that only about 3,000 students who scored in the top third of the city on state math exams picked a limited unscreened school as their first-choice high school, while roughly 14,000 of them chose a screened program.

Kathryn Malloy, the principal at Mott Hall Bronx High School, said the stratification makes it nearly impossible for schools like hers to compete with schools that use different admissions methods. “You’re being compared on an unlevel playing field when they serve completely different populations,” she said.

The temptation to cherry-pick grows when funding is on the line, said Amy Brown, a former city teacher who wrote a book about philanthropy and public schools. Many of the small high schools opened under Bloomberg boasted support from nonprofit groups. Those groups had a lot riding on the schools’ success, even as they agreed to support schools that couldn’t screen students.

“It looks really good to be unscreened, and have that door open to anybody,” Brown said. “But at the same time, what [private] funders want to see, they want to see numbers.”

Despite these incentives, the Department of Education does not have a comprehensive way to monitor how limited unscreened schools conduct admissions. The city has increased training and resources for schools and guidance counselors, and is having ongoing conversations with school administrators, education department officials said.

But that’s little help for Michael Zink, education director for the New York Foundling, a nonprofit that supports city children in foster care. He said he considers himself lucky if a handful of the roughly 30 students he oversees end up in schools with graduation rates over 80 percent. With these unwritten rules of high school admissions in effect, they almost always end up at extremely low-performing high schools, he said.

“When you look at certain high schools throughout New York City that generally have the worst student outcomes, you often wonder why anyone goes to those schools at all,” Zink said. “And the answer is, for the most part, it’s New York City’s most vulnerable young people.”