New York City is moving forward with a plan to dramatically reduce suspensions for its youngest students, according to a revised draft of the city’s discipline code released Friday, and will further limit the use of suspensions for older students.

The changes, which started coming into focus last summer and could take effect in several weeks, will all but eliminate suspensions in grades K-2, except in cases “when a student repeatedly displays behavior that is violent or could cause serious harm, or a student violates the Gun-Free Schools Act,” according to city officials.

Still, the new policy is not the absolute “end to suspensions” for the city’s youngest students the city promised in July.

Though suspensions in that age group have fallen in recent years — down to 801 last school year from nearly 1,500 the year before — the new policy is likely to have a dramatic impact. Officials said that if the proposed discipline code had been in place last year, just 25 students in grades K-2 would have been suspended.

“These changes are promising,” wrote Dawn Yuster, the social justice project director at Advocates for Children. “Students, regardless of their age, should not be forced to miss weeks, months, or a year of valuable instruction time.”

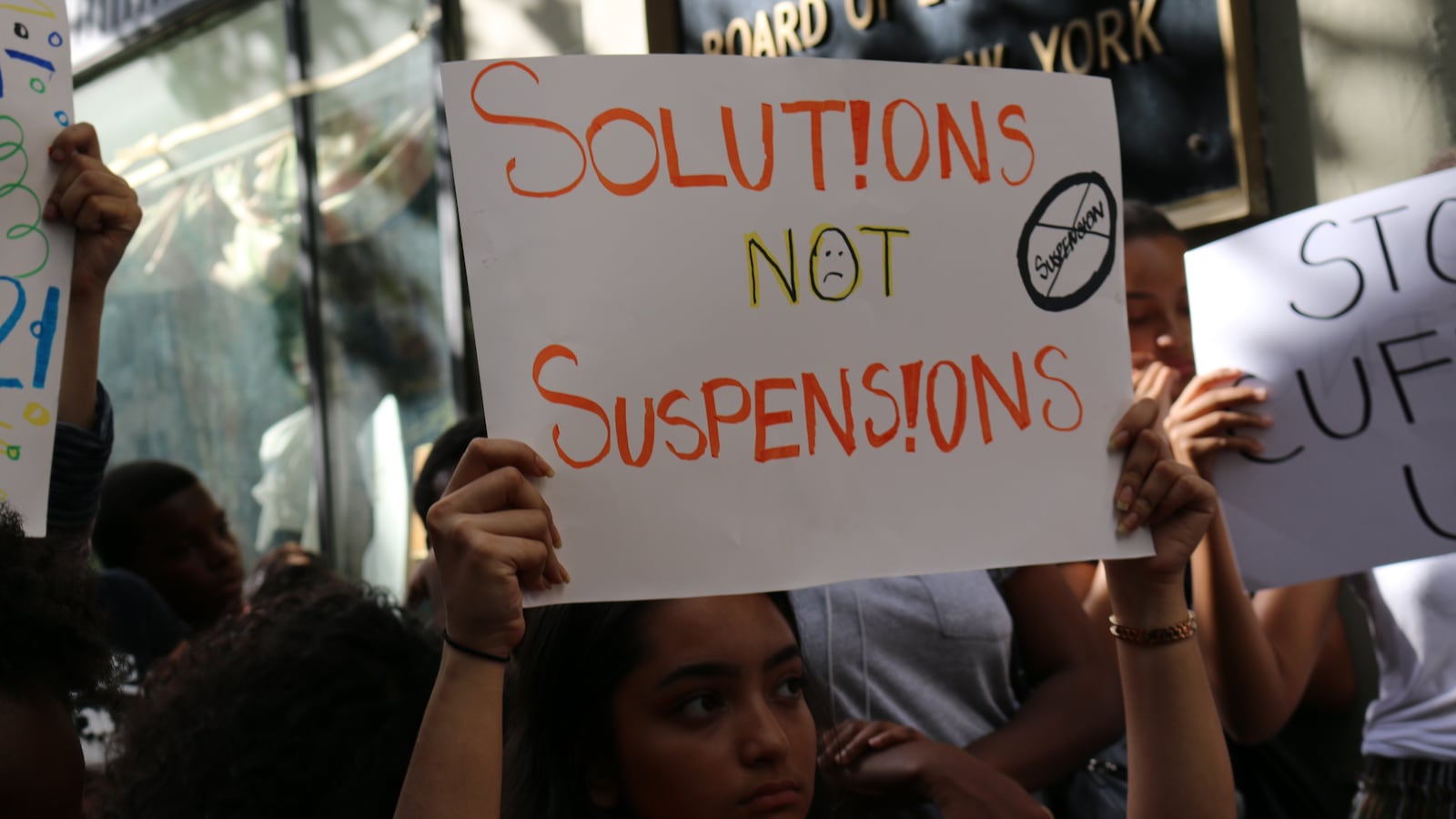

Still, several advocates said the changes were not sweeping enough, and don’t address serious disparities in suspension rates for students with disabilities and those of color.

“The incremental change is important, but it’s been incremental change for a decade,” Johanna Miller, advocacy director for the New York Civil Liberties Union, said in an interview. “We’re working with a broken system if we’re talking about telling a six-year-old it’s no longer appropriate to come to school.”

Most of the suspensions handed out to those students come from a small number of schools, and the most common reason for suspending students in that age group is for a category known as “altercation and/or physically aggressive behavior” that was once referred to as “horseplay,” a Chalkbeat analysis found.

The city is “committed to ending suspensions for students in kindergarten through second grade,” education department spokeswoman Toya Holness wrote in an email. “The proposed changes to the discipline code are significant steps toward meeting this goal.”

The changes would also affect older students: Suspensions would be eliminated as punishments for several infractions, and maximum penalties will be reduced for others.

In grades six-12, for instance, the maximum punishment would be reduced for 14 out of the 62 infractions listed in the discipline code for that age group. In grade three, the maximum punishment would be reduced for 14 infractions, and for grades four and five, the punishments would be reduced for eight infractions.

Kesi Foster, a coordinator at the Urban Youth Collaborative, an advocacy group that works with students on justice issues, said the proposed changes are a step in the right direction, but don’t address systemic problems.

“It’s hard for us to look at reductions in overall suspensions and feel as if we’re getting to the root of the problem, when the disparities remain sky-high.” He pointed to statistics that show black students, who represent 27 percent of the city’s students, account for half of all suspensions.

Foster added that suspensions for an offense called “insubordination” had not been eliminated, a reform advocates say could eliminate a subjective infraction often targeted at students of color (though principals must get approval before suspending a student for it).

The NYCLU’s Miller also noted that the discipline code has not been updated to provide clear guidance on how police officers should interact with students, including when handcuffs should be used.

The education department’s Holness pointed to overall decreases in crime, arrests and summonses and noted, “We are dedicated to addressing the disparities in school discipline.” The city is in discussions to update the agreement that governs how police interact with students, she added.

The United Federation of Teachers, which was critical of the discipline code changes announced over the summer, did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The union previously argued that the city has not adequately trained teachers in alternative discipline practices, a concern that has bubbled up in some schools.

Daphna Gutman, principal at P.S. 142 in Manhattan, cheered the suspension policy in an interview. “From my experience and my school, [suspensions are] not a useful tool. We think it sends the messages that you’re not welcome in the community. It’s essentially banishment.”

A hearing on the discipline code changes is scheduled for January 25 at Manhattan’s M.S. 131 and the Department of Education will accept public comment through January 30.