Two programs meant to limit student involvement with the criminal justice system will be expanded, city officials announced Monday.

This spring, 71 total schools will be allowed to issue warning cards instead of a criminal summons to students 16 and older for disorderly conduct or possessing small amounts of marijuana — expanding on a 37-school pilot program in the Bronx that currently operates under that policy.

Officials are also expanding the School Justice Project, a program that offers free legal help for students who have become tangled in the criminal justice system, along with “know your rights” trainings. Eleven total school campuses will join that program, up from just one, according to the city.

The programs are in keeping with Mayor Bill de Blasio’s push for less punitive approaches to school discipline, including “restorative” justice, and a plan to significantly reduce suspensions for the city’s youngest students.

But some advocates said the new measures are too incremental and unlikely to make a significant dent in the number of students — disproportionately black or Hispanic — who are slapped with criminal offenses at school.

“What the city is proposing to do is really minimal,” said Dawn Yuster, a student justice expert at Advocates for Children. She pointed out that school safety agents — who are posted in schools but employed by the NYPD — still have discretion to issue criminal summonses for what amount to schoolyard fights or minor drug violations, even in schools with the warning card program.

Even doubling the number of schools covered by the policy would only cover a fraction of the city’s high school students, Yuster added. “If they wanted to make a big change, there’s no reason why they couldn’t expand the program to all schools.”

But Dana Kaplan, executive director of youth and strategic initiatives for the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, defended the city’s approach.

She said expanding the warning card and School Justice Project programs is part of the city’s effort at “improving school climate while reducing unnecessary exclusionary measures.”

The warning card approach has had an effect: In the program’s first year, there was a 14 percent decline in summonses for small marijuana possession and disorderly conduct in the pilot schools, Kaplan said.

The city is implementing the program in schools that issue a larger share of summonses, she added, and expanding the program requires training school safety agents and other staff in the building. “We’ll be evaluating the warning card program and looking to how we can continue to increase its impact and scale.”

Other advocates cheered the expansion of those programs. “We are really happy with anything that reduces criminal court contacts for minor misbehavior,” said Johanna Miller, advocacy director for the New York Civil Liberties Union. Though “we would like to see the city dispense with using summonses in schools altogether.”

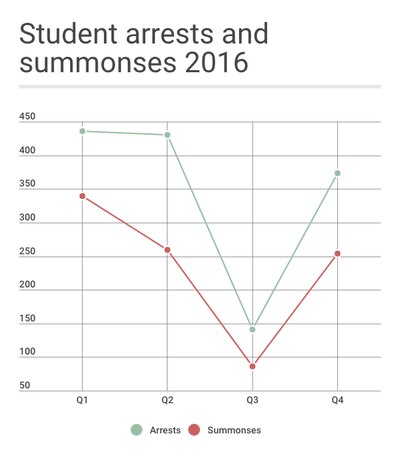

Also on Monday, the NYPD released new quarterly school safety data for the end of 2016 that show school-based arrests and summonses generally decreased last year. The City Council did not start requiring the NYPD to release these statistics before last year, making historical comparisons difficult. (Quarter three shows large declines because it covers much of the summer break.)

Still, the first six months of data collected last year show 91 percent of school-based arrests, and nearly 93 percent of summonses, were issued to black or Hispanic students (a population that represents nearly 70 percent of the school population). Black and Hispanic students are also much more likely to be handcuffed.

“The decrease in arrests and summonses is an indication the administration is trying to go in the right direction,” wrote Kesi Foster, a coordinator at Urban Youth Collaborative, an organization that promotes student voices in conversations about school discipline. But, he said, the numbers show hundreds of students each quarter are still coming into contact with the criminal justice system for minor violations.

“City Hall can and must do more to keep young people in the classrooms and out of courtrooms.”