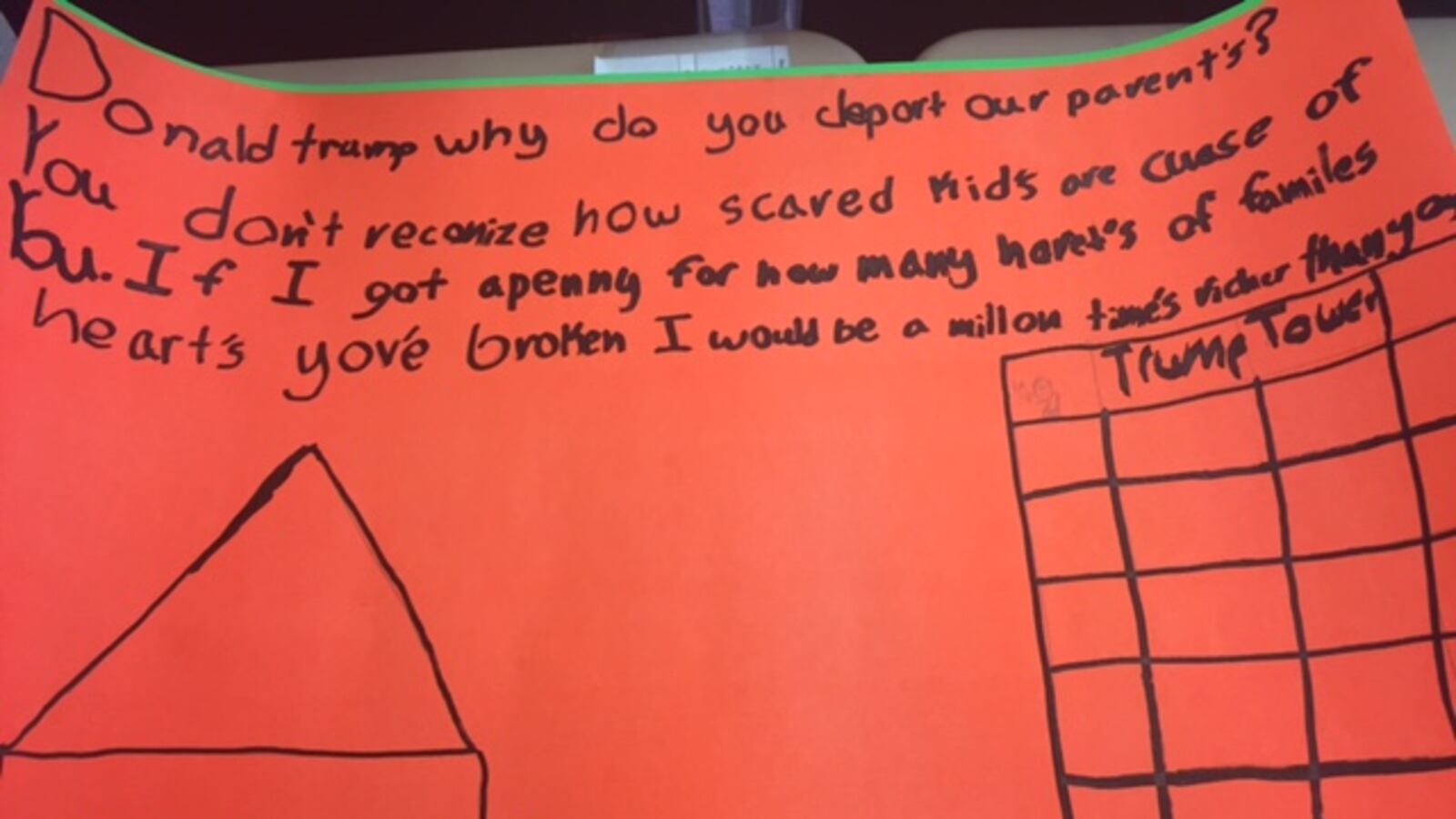

After the election, a student in Helena Yordan’s Bronx after-school program handed her a drawing with an image of an immigration agent arresting a woman.

The caption read, “Donald Trump, why do you deport our parents? You don’t recognize how scared kids are.”

That student is still attending the program, but Yordan said she’s worried about keeping other students in school and after-school as anxiety consumes many immigrant families.

This child’s mother, an undocumented immigrant from El Salvador who did not provide her name, said some Hispanic parents were afraid to visit the school and one of her friends was considering pulling her child out altogether.

While the mother we spoke with has no plans to keep her children home, she understands the impulse.

“I had the same fears,” she said. “I sometimes felt very insecure to go out in the street. I had nightmares.”

Those fears are reflected across the city. As the federal government ratchets up immigration enforcement — most recently by dramatically expanding the pool of undocumented immigrants who can be deported — families are increasingly hiding behind locked doors. Despite assurances from the city that it will safeguard students, advocates worry that families could leave schools next.

“The big issue is that there is pervasive anxiety across immigrant communities,” said Kim Sykes, who works on education at the New York Immigration Coalition. “They are afraid to do laundry. They are terrified of being separated. This anxiety extends to all areas of life and school is not exempt.”

Sykes recounted one instance in which parents, on their way to drop off a child at a child care center in the Bronx, thought they were being followed by ICE agents. Out of fear, they did not take their child to the center that day. (While some recent reports suggest Trump could be open to immigration reform, Sykes’s organization said it was unconvinced his attitude toward immigrants has changed.)

Roksana Mun, director of strategy and training at DRUM, an organization that helps South Asian immigrants, has heard some of the same concerns as Sykes. In private conversations and phone calls, she said, three separate families have told her they are worried about sending their children to school.

So far in New York City, these are anecdotal stories and fears. The Department of Education said there is no evidence of a widespread drop in attendance citywide or among specific immigrant-heavy communities.

“We want to make sure that parents send those kids to school. The best place to be protected is in your school,” said Chancellor Carmen Fariña at a Tuesday press conference. “We have not seen a dip in attendance and I want that to continue.”

The city sent a letter home to parents in January explaining that schools do not keep records of immigration status and will not allow ICE agents to access school buildings without “proper legal authority.” On Tuesday, she also said the city is drafting a second letter that spells out the protocol if immigrant agents show up at school.

City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, who made immigrant protection central to her recent State of the City speech, said she is looking into whether the city can strengthen its response. Even the rumblings of students avoiding school are troubling to her, she said.

“It may not be happening on a massive scale,” Mark-Viverito said, “but the fact that it’s starting to happen in some cases is a concern for us.”

Recent events seem to justify the parents’ fears. In Virginia and Texas, parents have reportedly been arrested or picked up by ICE agents while dropping their children off at school, according to the Washington Post. In Connecticut, there is anecdotal evidence that families might be keeping their children out of school, according to a spokeswoman for the education department.

And higher education has been impacted in California. The number of undocumented students applying for state financial aid there dropped more than 40 percent compared to last year.

This wouldn’t be the first time fear of immigration enforcement kept students from school.

In Durham, North Carolina, high school attendance dropped 20 percent last year after a student was arrested in an immigration raid. When Alabama enacted a sweeping crackdown on undocumented immigrants in 2011, which initially required schools to collect the immigration status of students, the Department of Justice documented a surge in Hispanic absences.

Some parents’ fears center not on the the safety of school itself, but on the threat of being separated from their children at all, said Ref Rodriguez, a member of the Los Angeles School Board. He started pushing for the L.A. to increase protections for immigrant students after he heard of a family that kept phone numbers on their refrigerator so the children would have someone to call if they came home from school one day and discovered their parents were gone.

“No child should come home and wonder whether or not their mom or dad is going to come home tonight,” Rodriguez said. “We’ve done things so that we can help people feel that that they feel secure and safe.”

Many local advocates want New York City to go further to reassure immigrant families. The fear, they say, is palpable — and widespread.

Darnell Benoit, director of Flanbwayan, a group that helps young Haitian immigrants, said he knows of Haitian parents who are planning to head back to Haiti and leave their minor children in someone else’s custody. Ninaj Raoul, executive director for Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees, said she has easily gotten 20 nervous calls a day since the election.

At this point, Benoit said, “anything can happen,” including parents pulling their children out of school. “People are definitely afraid.”

Christina Veiga contributed reporting