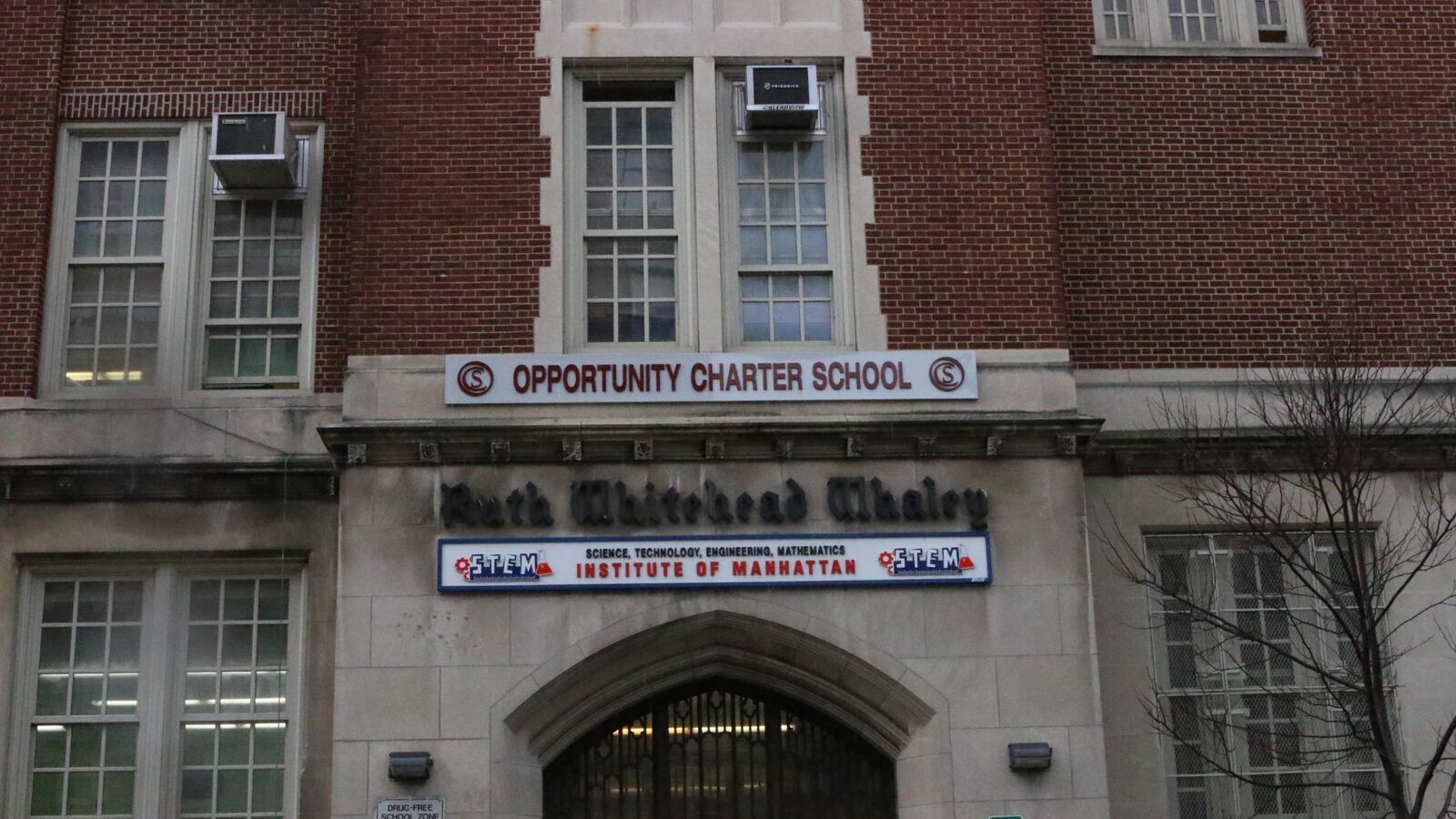

When Opportunity Charter School opened its doors a dozen years ago, it had an ambitious and unusual plan: to serve a population where over half the students have a disability.

This year, the school hoped to shift its mission even further in that direction — to stop accepting students without disabilities and shift its focus entirely to special education, while adding an elementary school to its middle and high school.

“Our mission is to take in the lowest-performing students,” said Leonard Goldberg, the charter school’s founder and CEO, explaining the decision to only serve students with disabilities. “You cannot successfully be all things to all children.”

But last week, the city’s education department publicly rejected the school’s expansion plan and moved to eliminate its middle school, citing poor performance. They also did not approve its proposal to exclusively serve students with disabilities. The decision has reignited a standoff between the school and the city — which tried to shut the school down entirely five years ago — about how to fairly evaluate schools like Opportunity, which serves the second-highest proportion of students with disabilities of any charter school in the city.

When Opportunity opened in 2004, the school’s mission was to educate students with learning and cognitive delays alongside typical students. The 423-student school offers intensive support for its students with disabilities, according to staffers, including a social worker and a behavioral and learning specialist for every grade. The school also partners with the Children’s Aid Society to offer mental health counseling and dental care.

On its face, the education department’s argument for downsizing Opportunity is simple: The school met few of its academic benchmarks, reaching four of 22 goals over the past two years.

Just 9 percent of students scored high enough on state reading tests to be considered “proficient,” compared with 13 percent of similar students at other schools. Three percent are proficient in math, compared to 9 percent in the comparison group. Officials who visited the school to help decide whether it should continue to be able to operate said they didn’t see strong teaching or challenging classes.

“Opportunity Charter School was given clear performance benchmarks over the last five years, and the middle school grades did not meet them,” education department spokesman Michael Aciman said in an email.

Opportunity’s leaders vehemently disagree with that characterization, and say the city did not adequately take into account the performance of their incoming students or accept their evidence of growth.

Roughly 85 percent of the school’s students are eligible for meal assistance and virtually every student is black or Hispanic, far above average for District 3. Nearly two-thirds of its incoming sixth graders scored at the lowest level on state tests, according to its charter renewal application.

“They get to us shattered — they’ve basically been told to sit in the back of the room with a box of crayons,” Goldberg said, “and they come to us and their world opens up.” He added that Opportunity plans to exclusively serve students with disabilities so the school can play to its strengths instead of stretching to serve students with a wide range of skills.

Opportunity officials pointed to some signs of success: Its graduation rate for students with disabilities exceeded the city average in four of the last five years, evidence the city used to keep the high school open. The school’s postsecondary enrollment rate also rivals the city average.

Still, its renewal application does not emphasize academic growth in its middle school grades.

James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center, said decisions about whether to renew charter schools are often complex, especially when the evidence of success is mixed.

But without commenting directly on Opportunity Charter, he said, “We created charters as alternatives to the system, to be more successful than the system, to have better outcomes.”

“It’s a very slippery slope to go from wanting an appropriate set of outcomes for a difficult-to-educate population, and using the fact that you’re enrolling a difficult population as a shield to protect you from accountability,” he added.

This is not Opportunity’s first disagreement with the city. In 2010, the city’s Special Commissioner of Investigation released a startling report that showed the school failed to adhere to its own policies in responding to cases where the staff used force against students or verbally abused them.

In a recent interview, Goldberg denied the report’s findings. He noted the school has worked to institute less punitive “restorative” approaches to student discipline, and the school has reduced its suspension rate.

A dispute with the city also flared up five years ago, when it tried to close the school entirely — a decision that was later reversed on appeal. Opportunity officials are hoping for a similar outcome this year, and have already submitted an appeal to the city, with a decision expected later this spring. The school will also face another test quickly, since the city’s renewal of the high school grades only grants the charter for three years, not the traditional five.

In 2011, after a contentious unionization battle, Opportunity teachers voted to join the United Federation of Teachers, the city teachers union, which has long lobbied against school closures. Current staff members and parents said in interviews that the school might have challenges, but oppose the city’s plan to shrink it.

Qays Sapp, a behavioral specialist at the school who graduated from Opportunity in 2011, thinks of the school as a “second home.” Still, he said that the school’s high turnover rate has had an effect on morale. Last year, 18 instructors — or 44 percent — left the school.

“I would be lying if I said the school doesn’t need some improvement,” Sapp said. But he thinks the middle school should stay open. “They’re not doing the kids any justice by shutting it down. Who’s going to take them?”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Opportunity’s request to only serve students with disabilities had been approved. In fact, the city rejected that plan.