On a recent Wednesday night, Superintendent Paul Rotondo listened to tear-filled pleas from students not to close their Bronx high school, Monroe Academy for Visual Arts and Design. He watched exasperated teachers criticize his recommendation to shutter the school. And he absorbed parent confusion over where their children would go school next year.

Rotondo made them a promise. “If this proposal passes, we will find you a better school,” he said, citing the high school’s low graduation rate (38 percent) and college readiness statistics. “I wouldn’t promise you something that’s not available.”

But what are the chances a student at Monroe, among the least successful high schools in the city, will wind up at a significantly “better” school if it closes?

It’s an important question for parents and students, as city officials are scheduled to vote this Wednesday on whether to shutter five more Renewal schools — low-performers that were offered extra academic resources and social services in the hopes of stoking a turnaround.

To assess the city’s promise of a better education for students at schools on the chopping block, Chalkbeat took a look at where students went after attending the only two Renewal high schools closed so far — Foundations Academy High School in Brooklyn and Foreign Language Academy of Global Studies in the Bronx. (A Renewal middle school also closed last year, but is not included in this analysis.)

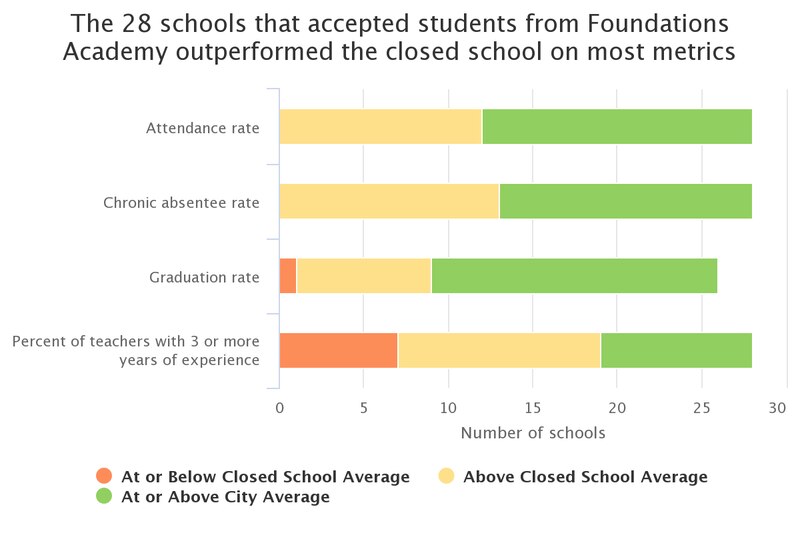

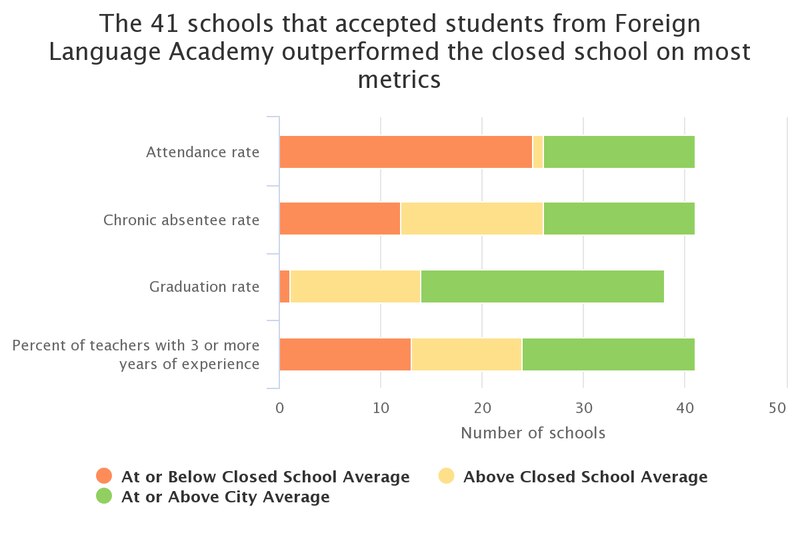

The data generally back the city’s claim. Most of the schools that accepted the displaced students posted higher graduation rates, attendance, and test scores — and have more experienced teachers than the schools they left. That isn’t entirely surprising; the schools that closed were considered among the city’s worst. But the schools those students later attended were, in some cases, also struggling, often performing below city averages on those same measures.

These findings come with an important caveat: The city data show which schools students later attended, but does not include how many students went to them, making it impossible to say what proportion of students went to higher- or lower-performing schools. Still, the numbers reveal an overall picture of the schools in which those students enrolled.

First the good news: Of the roughly 70 schools that accepted students from Renewal high schools that closed last year, 65 percent had higher attendance rates. Ninety-six percent had students with higher average scores on eighth-grade state math and reading tests, 97 percent had higher graduation rates, and 75 percent had a higher share of experienced teachers.

Almost every school that took in students from Foundations Academy, for instance, posted a graduation rate above 50 percent, the average at Foundations. Every single student who left Foundations wound up at another school with an attendance rate over 78 percent, their former school’s average.

Still, on those same metrics, many schools that took on students from closed ones underperformed city averages. More than half of the new schools had lower attendance and higher rates of chronic absenteeism than average. Three-quarters posted lower rates of eighth-grade math and reading proficiency, and three-quarters had higher concentrations of poverty.

But there are bright spots, even compared with city averages. Sixty-eight percent of the schools that took students in posted graduation rates above the city’s 72.6 percent average.

Chalkbeat’s findings dovetail with a previous study on school closures in New York City that found shuttering low-performing schools was linked to better academic outcomes among the students who would have attended them later.

But for students who were enrolled at the high schools when they closed, the evidence suggests little impact, according to James Kemple, executive director of the Research Alliance for New York City Schools, and author of the school closure study.

“The only research available in New York City suggests that closing a high school is not likely to have much effect — positive or negative — on the students who were enrolled in the school at the time of the closure,” he said.

That may not comfort many parents, some of whom worry about disruptions to their children’s education, or are skeptical that they’ll find significantly better schools.

Cecilia Cadette, a parent at Monroe Academy, said she doubts that her son Dontee will wind up at a school that is better able to serve him, especially given his complicated medical needs. Under a new principal, Monroe has been making strides, she said, and Dontee has started to find academic success.

“Now I have to make time to do some research, go around to the [Department of Education] to say, ‘OK, my son’s school is shut down and I need a school where they’re going to provide a safe environment and [where] he’ll continue to thrive,” Cadette said. “I dread going through that process.”

Officials have promised individualized counseling for parents and students to help them enroll at higher-performing schools. Students at closing schools will still have to fill out applications for up to 12 schools, as in the traditional admissions process, an education official said. Students will not be able to apply to screened, specialized or audition-based high schools — roughly one third of all city high schools — but the official said plenty of seats at strong schools are available.

Finding students a spot at schools that are technically higher-performing but still face challenges may not satisfy all parents, advocates and elected officials.

At an education hearing Tuesday, City Councilwoman Inez Barron raised doubts about the city’s approach. “I think every parent should have a right to send their child to a top-performing school,” she said. “Not to another neighborhood school which is doing marginally better.”

The Panel for Educational Policy will vote on the closures on March 22 at the High School of Fashion Industries in Manhattan. The meeting is scheduled to start at 6 p.m.

Sarah Glen contributed data analysis and Christina Veiga contributed reporting.