It was summer of 2016, and a school rezoning fight was raging on the Upper West Side. The battle over where kindergartners would attend school had, once again, dragged out an uncomfortable fact: New York City schools are starkly segregated.

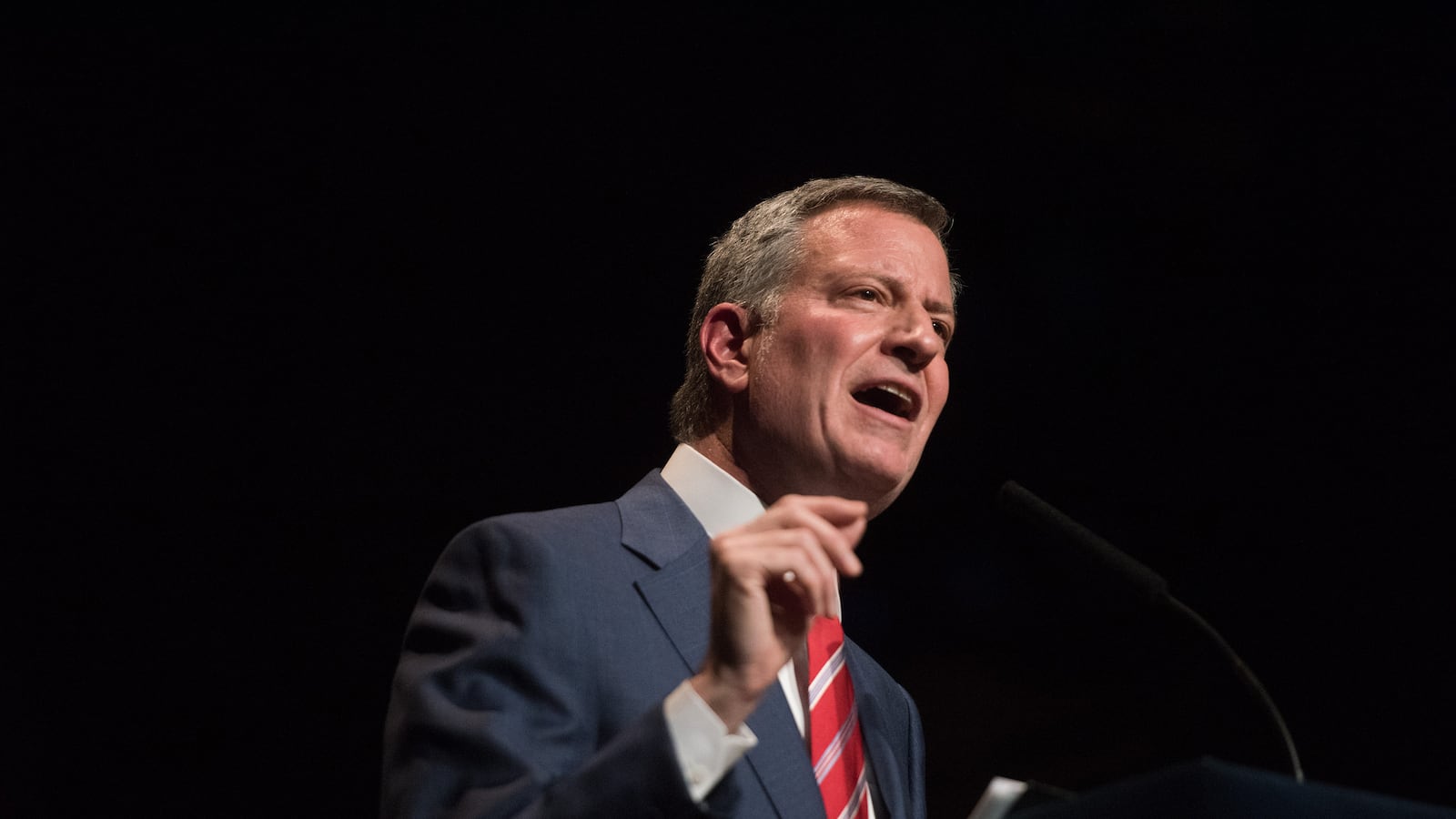

Parents railed against the city’s plans, which would send more white, affluent students to a school that largely serves black and Hispanic children from a nearby public housing development. Mayor Bill de Blasio, New York City’s unabashedly progressive mayor, visited the district. Faced with questions about segregation in the city’s schools, he promised that a “bigger vision” for integration was coming.

When it did — almost a year later — critics quickly blasted the plan as weak. Notably, the plan did not even use the word “segregation” and the mayor chose not to have a press conference when he released it. A recent study found that some of the plan’s goals could likely be met just through demographic changes already underway.

“I wish there was a bigger, stronger commitment,” Shino Tanikawa, an integration advocate in Manhattan’s District 2, told Chalkbeat at the time.

In the almost four years since de Blasio was elected, he has signed a paid parental leave policy, advocated against stop-and-frisk police tactics and called for more affordable housing. His education agenda has been similarly packed with progressive hallmarks, with the city pumping millions of dollars into struggling schools rather than closing them, and launching universal prekindergarten for 4-year-olds.

But while the city has taken some steps toward creating more diverse schools, de Blasio has poured little of his energy into integration. Why would a liberal mayor, who ran his campaign on a promise to tackle “a tale of two cities,” make only halting moves on an issue that seems core to a left-leaning agenda?

We spoke with a dozen parents, advocates, and academics, who say his constituents simply aren’t aligned on the issue — and he could risk losing their support if he tries a bolder approach. And despite the work of a growing network of activists, a notable advocacy gap means the mayor hasn’t faced intense pressure to act.

“It’s just a calculation that he’s made,” said Matt Gonzales, who works on school integration issues for the nonprofit New York Appleseed. “A lot of Democrats have been characterized as really progressive, but they commit all kinds of errors in their work.”

“People don’t want to give stuff up.”

Recent school rezoning battles are a prime example of why de Blasio might be hesitant to push for integration.

New York City schools are among the most segregated in the country, a fact that was thrust into national headlines by a 2014 report by The Civil Rights Project at UCLA. About half of all city schools are “intensely segregated,” with at least 90 percent of students belonging to a minority group, according to the report.

Some integrated neighborhoods offer opportunities to break that pattern. But when the city has proposed changes that would decrease segregation (as a byproduct of tackling overcrowding), resistance has been fierce.

In Brooklyn’s District 13, when the city proposed funneling some children from one crowded school’s zone to P.S. 307 in Vinegar Hill, a school that had largely served black and Hispanic students, white and affluent parents fought back.

The same thing happened in District 3 on the Upper West Side when the local Community Education Council voted to change the boundaries around three vastly different schools. Two were jam-packed and high-performing: P.S. 199 and P.S. 452, which enroll mostly white and Asian students. The third, P.S. 191, enrolls mostly black and Hispanic children from public housing across the street.

Backlash was swift, well-organized, and persistent. Parents opposed to the plans for P.S. 199 and P.S. 452 packed public hearings. They sent letters from lawyers, calling the process “contrary to law.” Many affluent parents said they’d move, rather than send their children to a lower-performing school.

“There’s a serious problem in white liberalism in New York City,” said Emmaia Gelman, a white parent in District 3 who has advocated for integration policies. “Put to the test, it doesn’t hold up. People don’t want to give stuff up.”

De Blasio has signaled he agrees, having once said the city should “respect families who have made a decision to live in a certain area oftentimes because of a specific school.”

Threatening that sense of entitlement could cost him votes, Gelman said. City Councilwoman Helen Rosenthal, who threw her support behind the Upper West Side rezoning, is now facing a competitive reelection race. De Blasio, on the other hand, is coasting toward a second term.

“The parents in my district are in survival mode.”

A fear of alienating white voters might be one concern for the mayor, but it’s not the only one. His black and Hispanic supporters aren’t necessarily pushing him on this issue either.

As the president of the Community Education Council in Harlem’s District 5, Sanayi Beckles-Canton ticks off the complaints about schools she often hears from parents. Some have safety concerns about their children who attend elementary schools co-located with charters that serve older students. Others have complained that their children receive special education services in a school hallway.

School integration just doesn’t make the list of top concerns in this district, whose students are 90 percent black and Hispanic.

“Before we can really get to the subject of integration, the parents in my district are in survival mode for the basics,” she said. “‘I just want to make sure my child is educated … before I care about you bringing wealthier families into my building.’”

What she does hear, however, are concerns about neighborhood gentrification trickling into schools. With wealthier families moving into Harlem, schools could lose federal funding for high-poverty schools if their low-income populations fall below the required threshold. That money pays for after-school care, arts programs and music classes. Beyond budgets, families also worry about losing their influence in schools.

“Some of the parents in my community are not excited about the notion of integration because it means losing things for them,” she said. “Those families who had the power and leverage in their schools, they’re losing it now because you have the more educated, wealthier families who are taking over.”

Some activists would rather see the city focus its efforts on providing culturally relevant education — making sure all students are reflected and supported in what is taught — within existing school communities.

“He’s not working with the urgency needed, and to make people believe that this is the change he wants to make,” said Natasha Capers, coordinator for Coalition for Educational Justice, a parent advocacy group.

As reluctant as de Blasio may be to rile white parents, he also can’t afford to lose the support of black and Hispanic voters. Half of black voters approved of de Blasio’s handling of public schools and 47 percent of Hispanic voters did, according to a 2016 Quinnipiac poll. But 54 percent of white voters did not.

“When he was elected, he saw that white progressive constituency as very important. It’s less important to his reelection because of liberal disaffection and strong support among the black and Latino voters,” said David Bloomfield, a professor of education at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. “Especially as he looks towards reelection, [integration] is not a pressing voter concern.”

“There’s not a massive movement for this yet.”

If voters haven’t clamored for integration, neither have most advocacy groups.

“If we want integrated schools, we need both real steps forward — real policy steps forward — and a much larger movement of people demanding it and choosing it,” said City Councilman Brad Lander who, along with Councilman Ritchie Torres, has been a vocal supporter of integration.

The United Federation of Teachers has pursued its own desegregation strategies, such as allowing schools to bend city and union contract rules when it comes to student enrollment, as well as lobbying for admissions changes at the city’s elite specialized high schools. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund was among a coalition of organizers that filed a federal complaint in 2012 targeting the specialized high schools exam.

The New York NAACP did not return a request for comment, but Hazel Dukes, president of the conference, was named to a city advisory group analyzing the school diversity plan. The teachers union defended its work.

“There are some people who want a louder voice. There are some people who don’t want us to speak about this at all,” said Janella Hinds, vice president for academic high schools at the UFT. “But I think we are chipping away at this issue in many different ways.”

The Alliance for School Integration and Desegregation is trying to bring together activists in a citywide movement, but it is a budding organization that is largely still figuring itself out. Made up of academics, parents, educators and others who have pursued integration in their own corners of the city, the group only settled on a name for itself in recent months. It has yet to attach that name to a list of policy goals and is still working out such basic questions as what its mission statement should include.

“There’s some legitimacy to the point that there’s not a massive movement for this yet,” said Gonzales of New York Appleseed. “You can still run around and talk to people on the street who have no idea that our schools are segregated.”

The advocacy movement that has sprung up is itself not that diverse, a critique that organizers say needs to be addressed before truly taking the cause mainstream. Naila Rosario realized the problem when serving as president of the Community Education Council in District 15, where parents have started working on a district-wide integration plan.

“I’m really a little frustrated that every time we have a diversity meeting, I’m the only Latina in the room,” she said. “If we do come up with a districtwide plan, I would like it to reflect the entire district — not just Park Slope and Cobble Hill.”

“If you try to do too much, people will flee.”

Another reason the mayor may be slow to act is the prevailing feeling that this problem is just too big to overcome. Before the city released its diversity plan, de Blasio cautioned it wouldn’t “instantly wipe away 400 years of American history and suddenly create a perfect model of diversity.”

He added: “Could we create the perfect model for diversified schools across the school system? No… Because you have whole districts in this city that are overwhelmingly of one demographic background. You would have to do a massive transfer of students and families in order to achieve it. It’s just not real.”

New York City schools have been segregated for a long time, and observers have noted that former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Chancellor Joel Klein barely touched the issue. At a March meeting of educators, Klein laid out part of his rationale.

“If you try to do too much, people will flee,” said Klein, as reported on an education blog. “The experience I’ve seen with forced busing: When people fled to the suburbs, the bulk of black and Latino kids were bused to hell and yon. To prioritize desegregation would have led to less good outcomes.”

Advocates have managed to agitate the current administration into taking some action. The diversity plan released in June set specific targets for increasing the number of students in racially representative schools and decreasing the percentage of economically stratified schools.

“In terms of beginning a conversation that suggests that diversity in New York City matters and that diversity can be part of a comprehensive plan, I do think that the advocacy community has made a bold victory here,” David Kirkland, executive director of the New York University Metro Center, told Chalkbeat in June.

Lander, the city councilman, understands the frustration many progressives feel when it comes to integration. But he also said the city’s plan provides a way forward.

“It’s hard to be satisfied with incremental change. On the other hand, to me the options are incremental change or no change,” Lander said. “I haven’t heard anyone propose what more rapid, comprehensive change would look like.”

In response to questions, de Blasio’s office emailed a statement that said “the Mayor believes students benefit from diverse and inclusive schools and classrooms.”

“That’s why we released a school diversity plan that says just that, and lays out a series of initial goals, policy changes and steps forward,” the statement read. “We know there’s lots of work to do, and the DOE is specifically inviting the feedback and ideas of community members and stakeholders… Feedback is central to the work of making our schools more diverse and inclusive.”

“A mayor who doesn’t want change”

In the places where advocates have tried to push harder or faster, the city hasn’t always helped. Take tiny District 1, for example, on the Lower East Side. The district of 12,000 students seems to have all of the ingredients to integrate its schools.

Parents have spent years building grassroots support to change elementary school enrollment policies there. And unlike many neighborhoods, the district’s demographics offer a real possibility to integrate students: 40 percent are Hispanic, 22 percent Asian, 18 percent white, and 16 percent black. District 1 also has the benefit of having no elementary school zone lines, with students assigned based on parent choice — meaning there are no attendance boundaries to fight over.

In 2015, the district landed a state grant to study and implement new enrollment policies to promote school diversity. They came up with a plan for “controlled choice,” which allows families to rank their preferred schools but also factors diversity into admissions.

Between that and de Blasio’s election, Naomi Peña, a parent on the education council, remembers feeling like the stage was thoroughly set for a change. “We were thrilled,” she said.

But Peña and other District 1 parents are still waiting. Rather than finding an ally in the mayor, Peña has accused the administration of holding their integration plans “hostage.” She blames bureaucratic delays that have held up grant payments and a general reluctance from the education department to approve enrollment policies that would deny parents their first choice for their children’s schools.

“What’s happening in our education department is an unwillingness,” Peña said, noting that their plan has been delayed until at least the fall of 2018. “I have a mayor who doesn’t want change.”