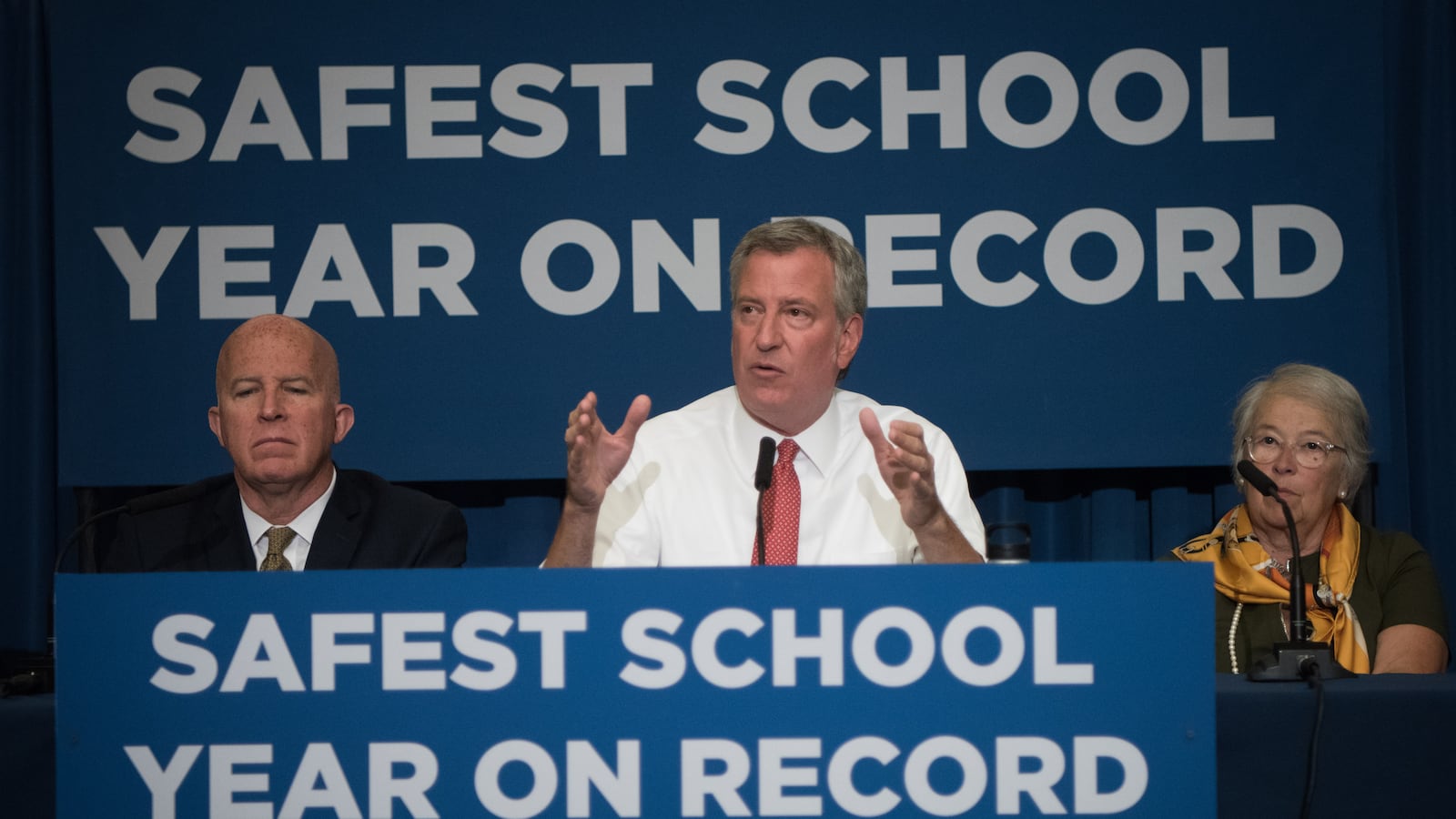

Just hours after a 15-year-old student was stabbed to death inside a Bronx high school, Mayor Bill de Blasio faced inevitable questions about what should have been done differently.

“Every decision about school safety,” he said in response to reporters’ questions, “is made with the NYPD.”

The police department’s deep involvement in school security stems from a nearly two-decade-old agreement between the police and education departments, which has never been updated.

As de Blasio continues his drive to overhaul school discipline and safety policies — limiting suspensions in favor of mediation, and cutting down on student arrests — advocates say that agreement has become a roadblock to reform. The agreement — known as a “memorandum of understanding,” or MOU — dates to 1998, a time when a harsh “zero-tolerance” approach to discipline ruled and serious crime in schools was more common.

Advocates for less punitive approaches to school discipline, which are often doled out disproportionately to students of color, say an updated agreement is long overdue. De Blasio seems to concur: One of the charges he gave a school-discipline task force that he formed in 2015 was to offer recommendations for an updated MOU.

The wait may soon be over: A new agreement is expected within weeks, said Dana Kaplan, Executive Director of Youth and Strategic Initiatives in the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, who is a co-chair of the task force.

“The document is highly outdated,” she said, adding that it should “codify the current practices” of the education and police departments, not those from the 1990s.

The MOU originated under Mayor Rudy Giuliani amid a wave of crime and complaints about the conduct of school safety agents. The agreement transferred responsibility for school safety from the education to the police department, and made the safety agents into civilian NYPD employees. It also offered guidance on handling crimes in schools and how safety agents should interact with school leaders and students.

School safety agents play a major role in student discipline: They patrol campuses, operate metal detectors and keep tabs on who enters and leaves school buildings. The NYPD’s school safety division — which was shifted to the police department under the 1998 agreement — contains thousands of agents, making it larger than the police force in most cities.

The MOU was intended to be updated every four years. Instead, it has never been revised.

Kathleen DeCataldo, executive director of the Permanent Judicial Commission on Justice for Children, who has pushed for a new agreement as a co-chair of the task force, called much of the MOU’s current language “pretty pernicious.”

“It’s all about school safety agents being involved in school discipline and reporting kids for anything that could be considered a crime,” she said. “You’re asking for a criminal justice response to misconduct in schools.”

The school-discipline task force that de Blasio convened — which is made up of advocates, educators and law enforcement officials — recommended a rewrite of the memorandum to reflect the city’s change in philosophy for keeping schools safe.

In a 2016 report, the group recommended that the agreement be revised to say that school leaders, not safety agents, should lead decisions about how to respond to student misbehavior. It also recommended that the MOU spell out new protocols for when agents search students and handcuff young students, and said it should require agents to read age-appropriate Miranda Rights to students when they are questioned.

“The position that I and many other advocates take,” DeCataldo said, “is that if you’re going to have police in schools, you’re going to have to be very clear about where the line is.”

An education department spokeswoman said the city is finalizing updates to the MOU.

“We work in close partnership with the NYPD to ensure the safety of all school buildings,” said the spokeswoman, Toya Holness.