Eva Moskowitz didn’t always aspire to be a champion of alternatives to the city’s public schools.

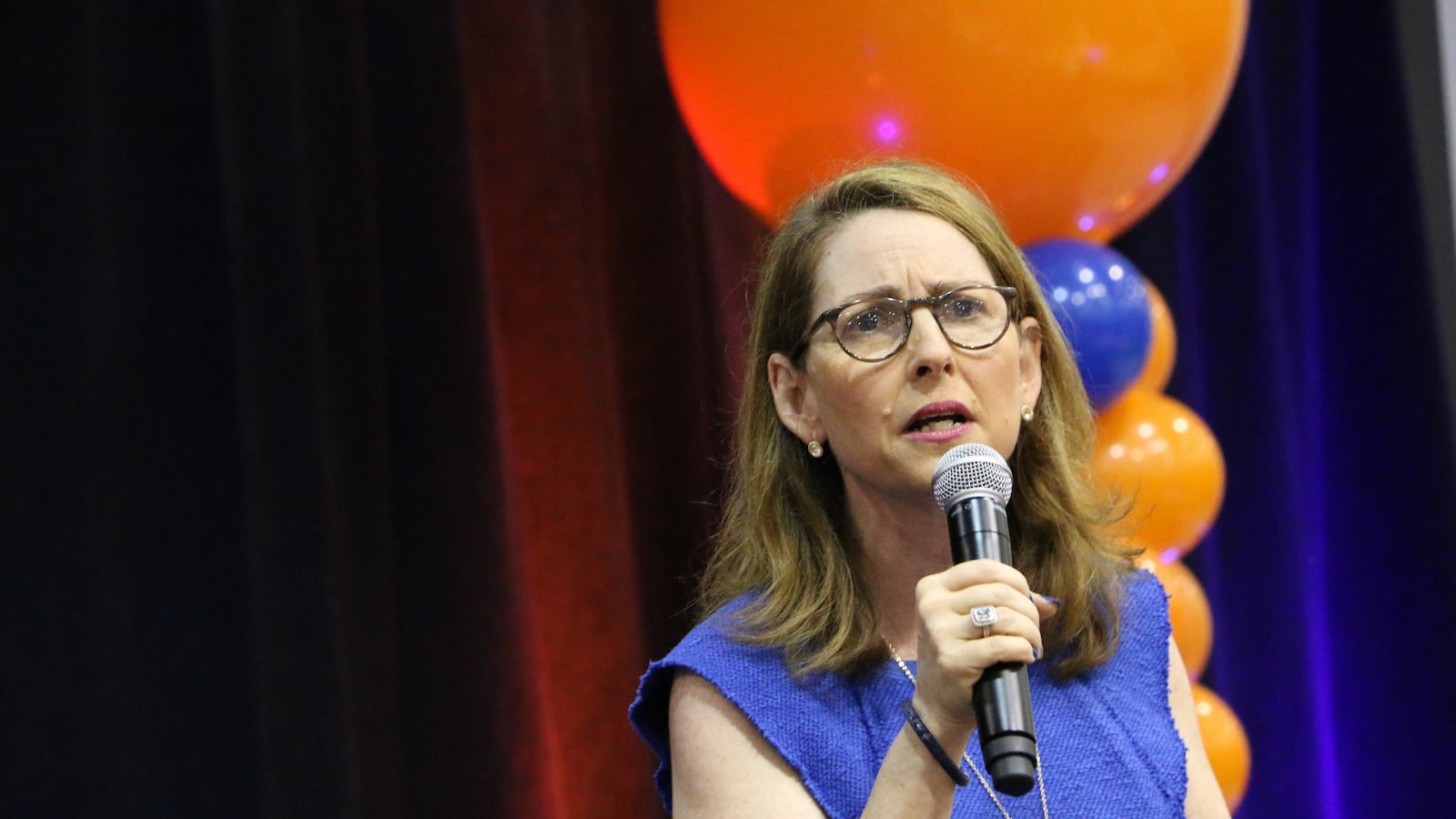

During an interview at a Chalkbeat breakfast event on Thursday, the high-profile — and often controversial — CEO of Success Academy Charter Schools explained her evolution from what she described as an “FDR Democrat” who believed the traditional school system was flawed but could be improved to an outspoken critic trying to lead an educational revolution from the outside.

Her transformation didn’t come from “reading Milton Friedman,” the free-market economist, she said. Instead, she described a gradual disillusionment with the traditional school system that began when she was a student at a Harlem elementary school, which she said was effectively “warehousing children,” and continued when she was a city councilwoman scrutinizing the city’s contract with the teachers union. (She claimed the union’s pushback against her contract probe made her feel like she was in one of the “Godfather” films.)

Success Academy is New York City’s largest charter school network, with 46 schools and 15,500 students. The network — which mostly serves black and Hispanic children — has extremely high test scores, which critics argue are largely the result of intense test preparation and strict discipline policies that push out the hardest-to-serve students.

Moskowitz and her schools have been the target of criticism from Mayor Bill de Blasio, who made challenges to charter schools a tenet of his first campaign, and Moskowitz a particular target (he said she should not be “tolerated, enabled, supported”). She has fought back fiercely, staging rallies and protests and demanding that de Blasio provide the charter sector with space for its classrooms.

Her clash with City Hall is in marked contrast with that of Michael Mulgrew, president of the city teachers union, who two years ago explained to the audience at a similar Chalkbeat breakfast what it is like to work with an ally in City Hall.

Moskowitz laid out for her breakfast audience her aggressive expansion plans — which she said she intends to pursue despite de Blasio’s resistance. She estimates the charter sector will serve about 200,000 students in four years (out of the total 1.1 million public school students in New York City) and wants to expand Success Academy to reach 100 schools.

Moskowitz recently released a memoir, which is full of personal details about her history and explains the backstory of Success Academy. She remains a pugnacious advocate for her cause, continuing to take on the unions and the mayor, while arguing that parent choice is central to making schools more equitable.

Here are some takeaways from the event, which was held at the Roosevelt House in Manhattan.

She decided early on that many district schools are failures.

Moskowitz attended a public elementary school in Harlem, where she said she and her brother were the only white students in the school. She described what she calls the “warehousing of children” and dubbed it “expensive babysitting.” When she attended Stuyvesant High School, she said, she had a French teacher who didn’t speak French and a physics teacher who was sometimes intoxicated.

As a teenager, she started helping Cambodian refugees find schools. In the neighborhoods they could afford, the schools were “God awful,” she said, while nicer schools were in neighborhoods out of their price range.

“It did stick with me that you were totally screwed if you didn’t live on the right side of the street,” Moskowitz said.

She believes unions and their contracts are a big part of the problem.

Ninety percent of schools “are not working at the most basic level,” Moskowitz said, a dysfunction that she argued is partly due to the rules in teacher and principal contracts.

After becoming chairwoman of the City Council’s education committee in 2002, Moskowitz held hearings on every aspect of the school system — including toilet paper. But her biggest showdown came when she decided to tackle the teachers union contract, she said.

“It is not a genteel sport when you take on the teachers union,” she said. “I had never felt like I was living a ‘Godfather’ movie before I took on the unions. It was a very scary undertaking.”

She envisions continued growth for the charter sector, but would not be pinned down on how large it would grow.

Though she has aggressive goals to expand Success, Moskowitz wouldn’t say what percentage of the city’s public schools should be charter schools. She called it a “hypothetical debate” and wouldn’t make a prediction for the future, saying she doesn’t have a “crystal ball.”

Parent choice is at the heart of her philosophy.

Moskowitz said parent choice is “fundamental” and the best bet for ensuring school qualify. Parents also are a bulwark, Moskowitz argued, to ensure that charter schools — which are run by private boards — will be responsive to the public will.

She also thinks charter schools should be held accountable for results.

Although charter schools are freed from some bureaucracy, they are highly regulated and do not operate in “some libertarian universe,” she said. She said she holds her own schools to account, believing that she should not increase the number of Success Academy schools unless all are high-quality.

She “urged caution” about trying to engineer diversity at charter schools.

Moskowitz thinks districts can “get the social engineering wrong” when they try to integrate schools by methods such as forced admission or busing. Instead, she argued, parents should be the engine that drives integration in charter schools through their ability to choose which schools their children attend.

The city should concentrate on integrating district schools, where admission to most elementary schools is based on the zones families live in, she said.

“I’m not sure we should put our energy into fixing charters on this front when they are already a much more open, accessible system than the zoned system,” Moskowitz said.