The city education department unveiled a suite of new anti-bullying initiatives Monday, just over a month after a student who claimed to have been the victim of bullying stabbed a 15-year-old classmate to death inside their Bronx school.

The $8 million package of programs includes a new online tool for families to reporting bullying incidents, anti-bullying training for students and school staff members, and funding for student-support clubs such as those for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students. In addition, the department will begin allowing bullying victims to request school transfers, will require schools to come up with individual plans for dealing with students who bully others, and will provide extra training and support to the 300 schools with the highest bullying rates.

“These new initiatives will build upon ongoing work to ensure that all schools have safe, supportive, and inclusive learning environments,” schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña said Monday during a City Council hearing on the issue of bullying Monday, which was scheduled after the Bronx stabbing that also left a 16-year-old student seriously wounded.

On Friday, Fariña announced that she had removed Principal Astrid Jacobo from the Urban Assembly School for Wildlife Conservation, the school where 18-year-old Abel Cedeno is accused of stabbing two classmates on Sept. 27. The local superintendent will help find a replacement and support the school in the interim, a department spokeswoman said.

Soon after the stabbings, reports of pervasive bullying and discipline problems at the school emerged; on surveys, just 55 percent of students there last year reported feeling safe in the school’s hallways, bathrooms, locker rooms, and cafeteria, compared to 84 percent of students citywide. In a jailhouse interview with The Daily News and the New York Post, Cedeno said schoolmates had long taunted him with racist and homophobic slurs. (Meanwhile, the slain student’s family has filed a notice that they plan to sue the education department for $25 million for failing to protect the victims, according to their lawyer.)

Fariña visited the school several times after the stabbing, which was the first student-on-student killing in a city school in over two decades. Still, as recently as last week she suggested during an interview on NY1 that no “red flags” had been “really apparent” before the violent episode, and that what had been reported by the media was not “necessarily the whole story” — though it was unclear what additional information she was referring to.

During Monday’s hearing, Bronx City Councilman Ritchie Torres criticized the department for failing to publicly explain why Principal Jacobo was removed from the school, and what discipline problems existed there prior to the stabbing.

“I’m concerned about the lack of transparency from the DOE,” he said.

Torres also asked the chancellor whether there was a “systemic” problem of bullying at that school. She responded that “there is obviously a problem” but that “systemic is a very big word,” adding that she would reserve judgement until the investigation is complete. Speaking to reporters after the hearing, Fariña did not offer any explanation as to why she chose to remove the principal other than to say it provided the school a “fresh start.”

“I think it’s a fresh start for everyone and I think it’s an opportunity to start with a clean slate,” she said.

Throughout Monday’s hearing, city council members raised questions about how the education department responds when school surveys reveal large numbers of staff or students who feel unsafe, and whether the city’s bullying statistics are reliable.

Councilman Daniel Dromm, chair of the education committee, rattled off statistics from multiple schools where large numbers students and staff reported that they did not feel safe or faced bullying.

Fariña said the city does review survey data, and that troubling results prompt extra scrutiny from education department officials. “Once the numbers skew in any one direction we have at least one person who’s looking at them very closely,” she said.

Officials also faced questions about whether the city’s bullying statistics reflect the true number of incidents.

Last school year, 3,281 incidents of bullying, harassment, or intimidating behavior in city schools were reported to the state, Fariña said. But more than 700 schools reported zero incidents of bullying, Dromm said, and a 2016 report by the State Education Department and attorney general found “significant underreporting.”

Education officials emphasized that many incidents of bullying are never reported to school personnel or are not serious enough to merit reporting to the state.

The new online bullying-complaint tool is set to launch in 2019, officials said. Families who report bullying or harassment will be informed within one day that their complaint was received, and within 10 days will be told the outcome of the investigation.

In the past, families could request that their children be transferred to a different school if they were the victim of a violent crime in the school or if they felt their children were unsafe there. The new policy will now allow “safety transfer” requests by any student who has experienced bullying, the department said.

In addition to the new programs and policies, the education department will begin publicly reporting the number of substantiated incidents of bullying, harassment, intimidation, or discrimination at each school. City Council members had previously proposed a bill that would require the department to release that information; on Monday, the department said Fariña supported the bill.

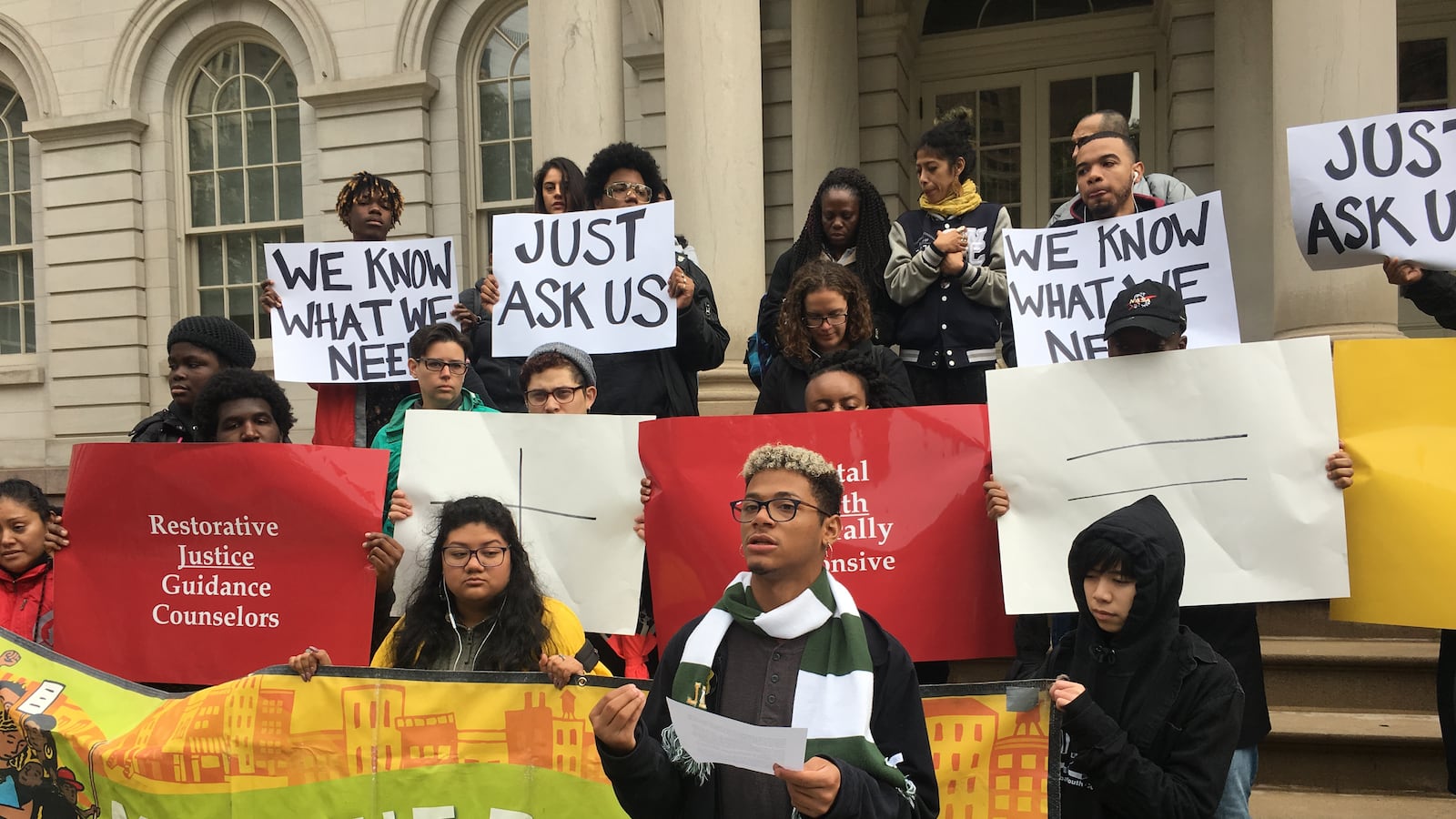

The anti-bullying measures announced Monday drew mixed reactions from advocates who said they were glad the city is taking action, but questioned whether these steps are enough to root out systemic problems.

Dawn Yuster, the school justice project director at Advocates for Children, said elements of the city’s plan were not yet clear, including precisely how the city will intervene in the 300 schools they plan to identify with higher rates of bullying.

“All of this is coming out on the day of a hearing prompted by a tragedy and we don’t know some of the details behind these initiatives,” Yuster said. “It’s promising, but it’s not enough.”

Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said she appreciated that officials are devoting more resources to bullying prevention, but said a larger investment is needed to fundamentally change how schools respond to student conflicts and misbehavior.

“There are still a thousand more school safety agents than guidance counselors and social workers,” she said. “And that speaks too loudly about where the city is investing its resources.”