Should high-achieving students attend one set of schools and everyone else another?

The question gets at a longstanding debate in education over sorting students by ability into separate classrooms or schools: Does it benefit the top students by providing them a more rigorous curriculum than is possible in a mixed-ability setting, or does it widen racial achievement gaps and leave lower-achieving students in less demanding classrooms with fewer resources?

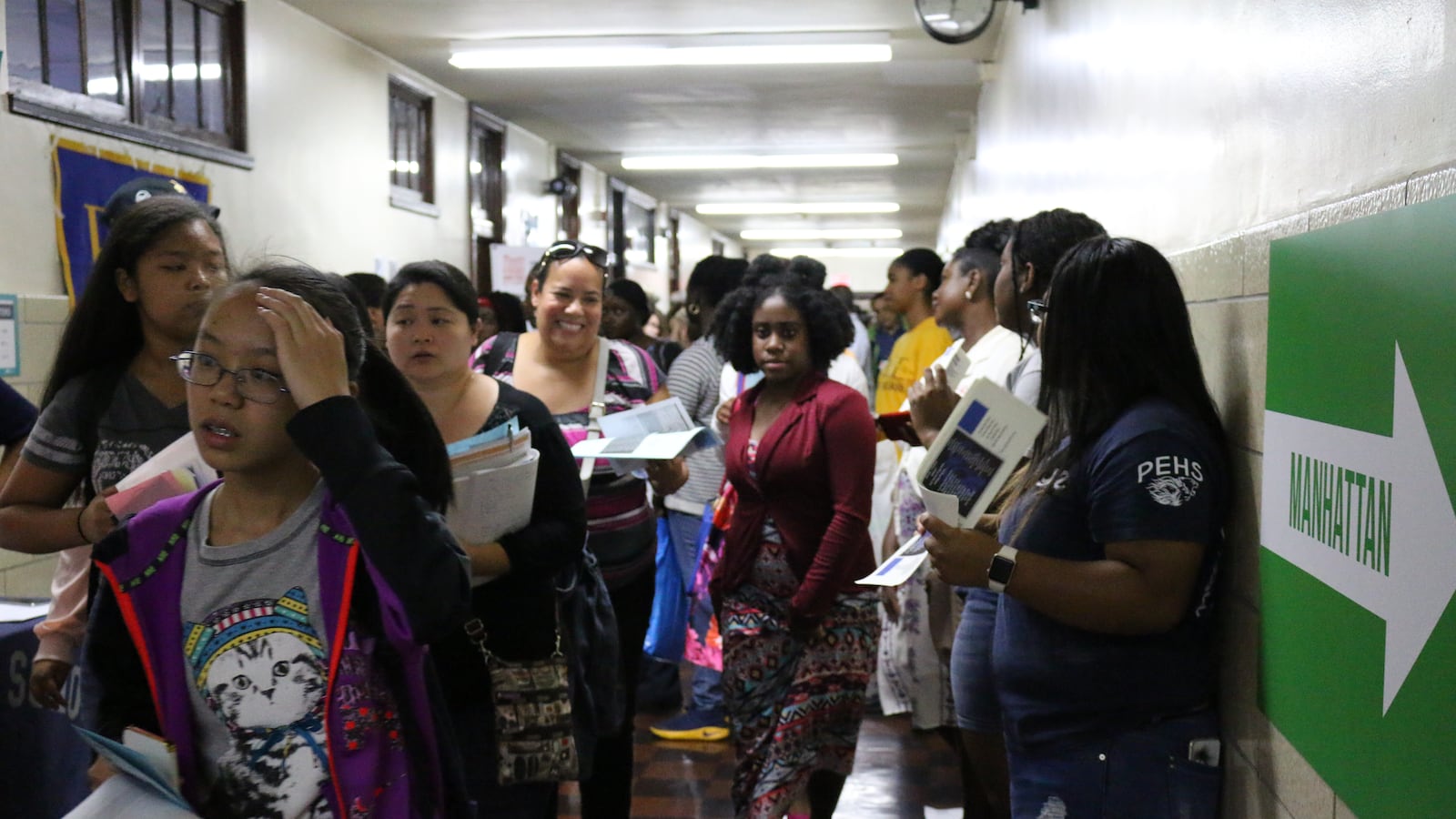

Some New York City schools “track” advanced students into separate gifted-and-talented programs or honor courses. But some whole schools are also designed for high-achievers: Roughly a quarter of the city’s middle schools and a third of high schools screen applicants based on their grades, test scores, artistic talents and other criteria. Some of the city’s most renowned high schools — the elite “specialized” schools that include Stuyvesant and Bronx Science — only admit the top scorers on an entrance exam.

This school-wide sorting system has come under fresh scrutiny lately as city officials rethink admissions policies in an effort to get schools to enroll more diverse populations. But even as critics say that selective schools worsen segregation and leave low-achieving students in low-performing schools, supporters — including many parents — say that advanced students learn best alongside similarly skilled classmates.

This debate flared up recently at a Chalkbeat event focused on high-school admissions. During the event and in follow-up questions submitted by readers, many people asked: Why do some city schools get to select their students? And are there alternatives to the current system?

To find the answers, Chalkbeat studied the research, consulted experts, and spoke with parents. Here’s what we found:

What’s the case for screened schools?

When Sharon Kaplan was in school, it “wasn’t cool to be smart,” she said. There wasn’t enough interest in advanced history to justify a class, so she took basic economics instead, where she learned to write checks.

When Kaplan had children of her own, she was determined to send them to selective schools where their classmates would be as eager to learn as them.

“Having other kids in the class who are similarly engaged really raises the level of learning that’s available to them,” said Kaplan, who has one child at Stuyvesant and another who attended the High School for American Studies.

Some, like Kaplan, argue it’s easier to teach and learn when students are sorted by ability. How much you learn has a lot to do with who your classmates are, many parents say. And some evidence supports them: For instance, researchers found that when hurricane evacuees arrived in Houston, low-achieving students who entered the schools negatively impacted high-achieving students’ learning, while high-performing newcomers boosted their performance.

At the same time, teachers may have an easier time when their students aren’t at widely different skill levels. And selective schools may be able to offer more advanced classes, since they have enough high-performing students to fill the seats.

There’s great demand for selective schools. Popular screened schools like Manhattan Hunter Science, Millennium, and Manhattan Village Academy each had thousands of students list them as one of their 12 high school choices, despite having less than 200 openings each. Across the city, the demand for seats at selective schools far outstrips the supply.

Gifted students can fall through the cracks. Under the recently replaced No Child Left Behind law, schools were under pressure to lift up students just below grade level. As a result of that intense focus on struggling students, their above-average peers have often got short shrift.

Sorting by ability may benefit high-achieving kids. There is limited research on the impact of selective schools. But the research on sorting students into separate classes by ability, called academic tracking, has found mixed results for high-achieving students.

One meta-analysis found that classroom-level sorting harms low-achievers’ performance but has no effect on high-achievers. Other research, however, has found benefits for those students. One study found that high-achieving black and Hispanic fourth-graders saw their math and reading scores rise when they were placed in gifted classes; another found that states with larger shares of eighth-graders in high-track math classes also have larger shares of students earning top scores on Advanced Placement exams in high school.

“The research is very clear that ability tracking helps high-achievers,” said Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and a proponent of tracking.

It’s a way to keep middle-class families in the public school system. Finally, there’s a more practical reason to advocate for screening, said Samuel Abrams, a researcher at Columbia University’s Teachers College. Selective schools are a way to keep middle-class families worried about the quality of the average public school from opting into private school or decamping to the suburbs. City leaders are “fundamentally concerned about white flight, middle-class flight,” Abrams said; elite selective schools are one way to keep more affluent families — along with their time and resources — invested in the public-school system.

What’s the case against screened schools?

Tanesha Grant’s daughter longed to attend LaGuardia High School, the celebrated — and highly selective — visual and performing arts school in Manhattan. But she didn’t get in.

Afterwards, she felt like a failure, Grant said. Now in ninth-grade at Urban Assembly School for Performing Arts, her daughter sees a therapist to work through the rejection.

“What are we putting them under immense pressure for?” Grant said. “The only point that I see is that it puts kids at a disadvantage and it separates kids into groups. The system makes the children unequal.”

Screening contributes to racial and socioeconomic segregation. The city’s eight most selective schools, which base admissions entirely on the results of an entrance exam, are disproportionately white and Asian. Only 10 percent of admissions offers went to black and Hispanic students, even though they represent about 70 percent of city students. A similar trend holds for the larger number of high schools that use a variety of criteria to screen applicants, though the racial disparities are less extreme, according to a Measure for America analysis produced for the New York Times.

A number of factors contribute to the racial imbalance — from the quality of the elementary and middle school that students attend to their parents’ ability to help them navigate the selective-admissions process. Some critics argue that the very act of admissions screening screening favors white and affluent students and disadvantages low-income students of color. Among the critics is Jeannie Oakes, a professor emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles, and a prominent opponent of tracking.

When it comes to sorting students by ability, she said, it’s hard to imagine “that our deep racism and classism in this society could ever be overcome by some sort of fair selection process.”

Sorting can hurt low-achieving students. A body of research shows that lower-achieving students fare worse when separated from their high-achieving peers. A 1999 report summarizing tracking research concluded that “low-track classes are typically characterized by an exclusive focus on basic skills, low expectations, and the least-qualified teachers.”

In a sense, New York City’s system of selective schools amounts to tracking at the school — rather than classroom — level. The most popular selective high schools drain off the highest-performing students, leaving a large portion of schools with few, if any, students who had passed the state exams in eighth grade. Those schools can become the equivalent of “low-track” classes.

It’s unclear whether high-achieving students are helped. Several recent studies call into question the benefits of attending a selective school. Researchers found that, in Chicago, students who attended selective schools did not benefit academically compared to students with otherwise similar backgrounds who attended non-selective schools. Another study showed that students who just missed the cutoff to get into one of New York City’s entrance-exam schools were no less likely to attend or complete college than those who did get in.

What are the alternatives?

Eliminate or reduce schools that base admissions on academic achievement. Some critics say academic sorting, segregation, and inequality are inseparable — so screening should be banned completely. Others say there should just be fewer selective schools. Officials in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration have said they don’t plan to open any new screened schools — but they haven’t agreed to get rid of existing ones.

Allow schools to screen, but tweak the admissions system to promote diversity. It’s possible for some high schools to remain selective but also become more diverse, advocates say — if the city changes the way it matches students with schools. The city’s admissions algorithm, which takes in students’ high school choices and spits out matches, could be tweaked to factor in information such as parents’ education level or students’ ability to speak English fluently, advocates say. That would be a way to ensure that privileged and needy students are spread more evenly across schools — including those that screen applicants.

“The entire trajectory of the lives of hundreds of thousands of students could be improved for the better through a mathematical adjustment to the system,” said Elijah Fox, a member of IntegrateNYC4me, a student group that advocates for more diverse schools. “It’s inspiring.”

Create a more consistent and transparent screening process. The city’s admissions system can resemble the Wild West with each selective middle and high school setting its own requirements. Often the criteria are hard to find and require students to attend school tours, take tests, or sit for interviews. Meanwhile, it’s nearly impossible for the education department to police whether schools are following their own rubrics or rules.

Standardizing the process could make it more fair. For instance, the city could create a common application for all selective schools.

Diversify exam schools. City officials have tried to increase the diversity at the specialized high schools by expanding programs like DREAM, which prepares students for the entrance exam. Others have proposed more radical solutions, like offering seats to the top students in every middle school. However, city officials have limited power to overhaul their admissions policies, which are written into state law. (Advocates argue that the law only mandates an entrance exam for the three original test-based specialized schools, but city officials say the law applies to all eight.)