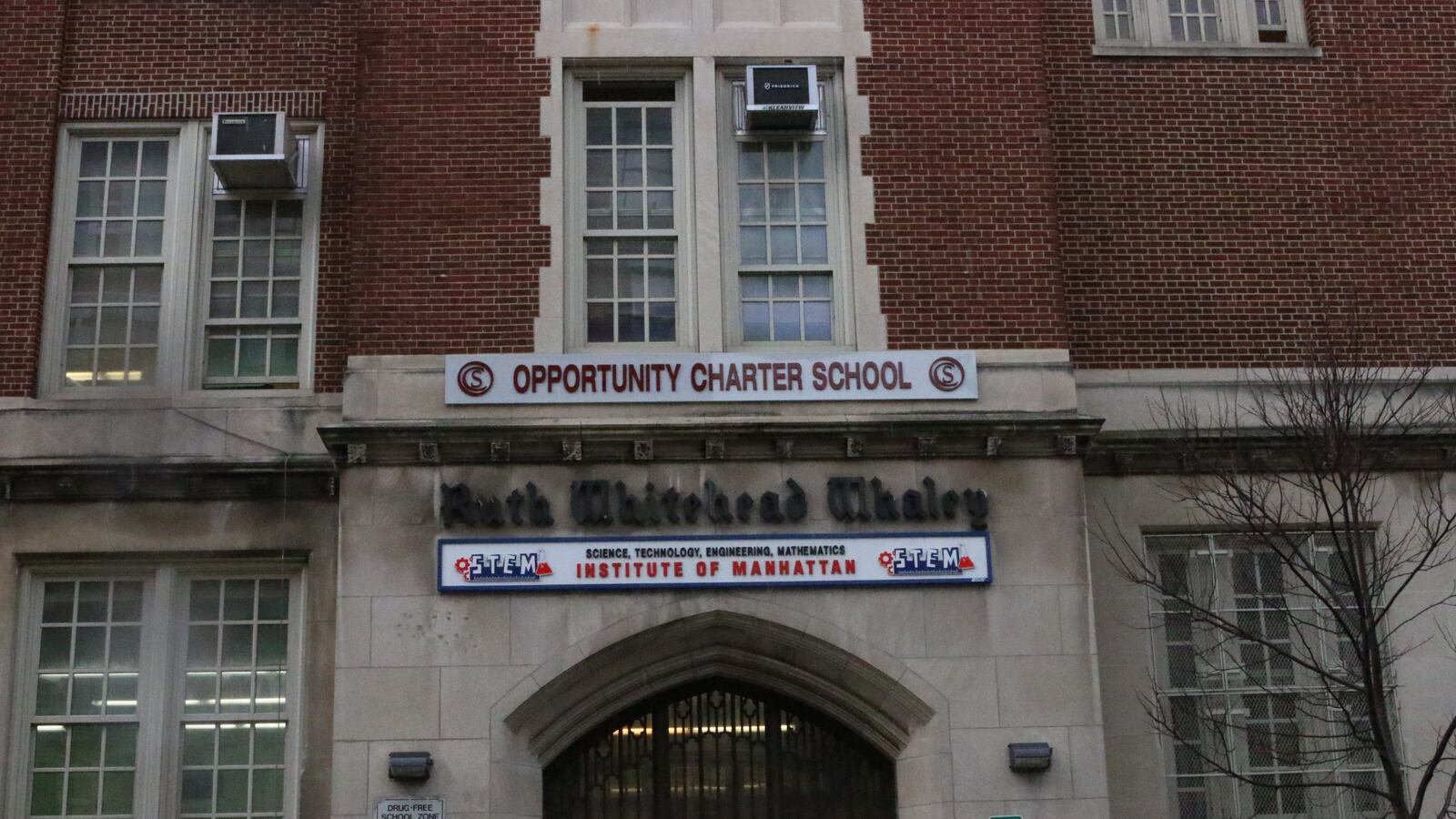

When New York City tried to shut down Opportunity Charter School’s middle school earlier this year for poor performance, the Harlem charter immediately went on the offensive.

School officials and parents filed a lawsuit, claiming the education department’s decision was too focused on test scores and didn’t take into account that more than half its students have disabilities. The grade 6-12 school explored switching authorizers so that the city — which granted the school its charter and must renew it on a regular basis — would no longer control its fate.

And just weeks after the city moved to shutter its middle school grades, the school brought on a high-profile public relations team whose president has represented members of the Trump family, while also paying a separate firm to lobby city officials on its behalf.

It’s not unusual for charter schools to work with outside public relations firms. But even some charter school advocates suggested that the school’s aggressive attempt to block the city’s sanctions is in tension with a fundamental premise of the city’s charter sector: that in order to justify their existence, charter schools must show that their students are making significant progress.

“It’s not just choice for choice’s sake,” said James Merriman, CEO of New York City’s Charter Center, referring to the city’s charter schools. And while he said there’s nothing inherently wrong with hiring a PR firm, he added: “Mounting a political and public relations campaign” has not helped other schools earn extensions of their charters because New York authorizers have “focused appropriately” on school performance.

The city has repeatedly said that Opportunity Charter School is not up to snuff.

In response to the school’s bid to renew its charter earlier this year, education department officials said it had met few of its academic benchmarks, reaching just four of 22 goals over the previous two years. And few of its middle-school students demonstrated proficiency on state tests, which showed that 9 percent of students were proficient in reading and 3 percent in math — lower than similar students at other schools.

Citing poor performance, the city attempted to close the middle school, granted the high school only a short-term renewal, and rejected the school’s bid to add an elementary school. They also denied the school’s proposal to exclusively serve students with disabilities, instead of its current mix of students with and without special needs. (Five years ago, the city moved to close the school entirely.)

School officials have vehemently disagreed with the city’s assessment.

They argue that evaluators have not adequately accounted for the school’s unique population, which was 55 percent students with disabilities in 2016. Today, only two of the city’s charter schools serve more students with disabilities. In addition, most of its incoming sixth graders had scored at the lowest level on state tests in elementary school, according to the school’s charter-renewal application. The school also notes that its high-school graduation rate among students with disabilities has frequently exceeded the city average.

After the city moved to close its middle school, Opportunity sued, claiming the decision discriminated against students with disabilities. In the meantime, the middle school has been allowed to remain open while a judge considers the case.

Kevin Quinn, a lawyer representing the school, said Opportunity isn’t trying to subvert the accountability system.

School officials’ position “isn’t that they shouldn’t be held accountable,” he said. “It’s that they should be held to a standard they could reasonably meet.”

As they fought to remain open, school officials explored the possibility of switching authorizers to the state education department.

Quinn said the school requested an application to make the state its authorizer, but did not receive one. However, state education officials said they determined that the school did not meet the legal standard to transfer authorizers. A spokeswoman did not say which requirement the school failed to meet, but the law stipulates that schools “in violation of any legal requirement, in probationary status, or slated for closure” cannot change authorizers.

Meanwhile, this March, the school hired Risa Heller Communications to manage media coverage of the city’s efforts to close the middle school and counter the city’s narrative that it is underperforming, according to a six-month contract obtained by Chalkbeat under the state’s Freedom of Information Law. Risa Heller, the firm’s president, once served as a spokeswoman for New York Senator Chuck Schumer and has previously counted Ivanka Trump and her husband, Jared Kushner, as clients.

Meanwhile, as the school’s battle with the city continued to simmer, Opportunity paid about $50,000 to a lobbying firm to make its case to the education department and City Hall, along with other city officials, records show.

The school’s PR firm also continued to press its case to reporters — touting the school’s graduation rates and pitching an op-ed by the school’s CEO, in which he took a swipe at the city’s record on serving students with disabilities.

The firm’s contract was for $9,000 per month. It stipulated that Risa Heller Communications would “manage media around DOE hearing” where the school made its case to stay open, and identifying “media opportunities for raising the profile of OCS.”

Neither Opportunity Charter School nor Risa Heller Communications responded to emailed questions about whether they had extended their agreement beyond the original six-month term, or used public money to finance the contract.

“Opportunity Charter School hired a public relations firm to raise awareness of our unique approach to serving students,” Jason Maymon, the school’s in-house public affairs director, wrote in an email. “As we have limited internal communications staff, we retained a firm to help with this function.”

The latest dustup with the city’s education department isn’t the school’s first public relations crisis.

In 2010, the city’s Special Commissioner of Investigation released a startling report that showed the school did not appropriately respond to allegations that staff members used force against students and verbally abused them. (The school has previously denied the report’s findings.)

In the wake of that report, the school’s legal team hired Mark Alter, a New York University professor, to help conduct an internal review of the school’s climate. Alter went on to become a member of Opportunity’s board, before leaving in 2016.

In an interview, Alter said he was attracted to the school because of its commitment to including students with disabilities alongside their typically developing peers. But the school was “always under the gun” because of its low test scores, which he says was never a fair standard to evaluate the school’s progress.

Asked about the school’s decision to go on the offensive, including hiring a PR firm, Alter said it made sense to him.

“You do what you need to do in order to survive,” he said.