Five months after New York City officials announced a much-anticipated plan to address school segregation, an advisory group that is supposed to help put the plan into action is finally starting to take shape.

Behind the scenes, city officials have been recruiting potential members, while the group’s leaders have started some initial planning before the first full meeting on Dec. 11.

Chaired by high-profile civil rights leaders, their charge is to spearhead an independent effort to turn the city’s general plans into specific recommendations for how to spur integration in the country’s largest school district — and one of the most segregated.

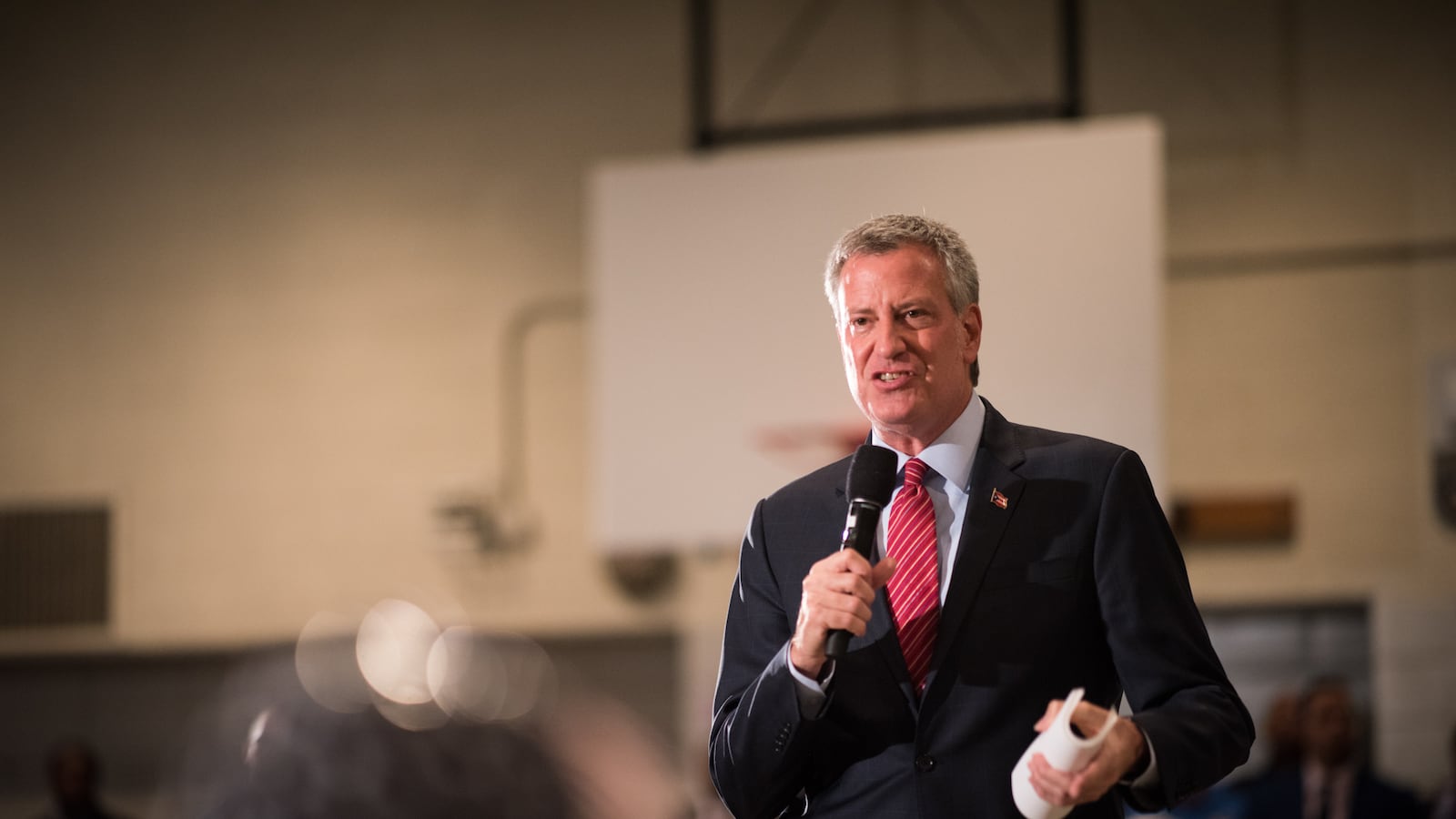

Advocates have held out hope that the group will push Mayor Bill de Blasio to move faster and further on integration in his second term than he did in his first. But they also have reason to temper their expectations.

Establishing the group bought de Blasio another year to act on the politically volatile issue, a tactic he has deployed on other controversial matters including rising homelessness, the Riker’s Island jail, and contested public monuments. The integration group’s recommendations may not be released until December 2018, one member said — about six months after the original deadline, and several years after advocates began demanding action on segregation. And even then, city leaders can pick and choose among the recommendations, which are non-binding.

“Politics 101 is: When you don’t want to decide, appoint a commission,” said David Bloomfield, a professor of education, law, and public policy at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center.

To lead the work, the de Blasio administration chose respected figures who can speak with authority on race and segregation — but who are not advocates who have demanded aggressive action. They are José Calderón, president of the Hispanic Federation; Hazel Dukes, president of the NAACP for New York State; and Maya Wiley, former chair of the Civilian Complaint Review Board, who previously served as de Blasio’s legal advisor.

Wiley, who is also professor of urban policy and management at the New School, said the group would try to boil down a decades-old problem with roots in housing policy, school-assignment systems, and structural racism to a set of realistic solutions.

“We’re looking for things that are actionable,” she said. “This is a big and complex set of questions.”

More recently, two additional members have been named to the group’s executive committee: Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation who is a longtime proponent of socioeconomic integration; and Amy Hsin, associate professor of sociology at Queens College.

The chairs have held at least two private planning meetings, and will continue to meet every six-to-eight weeks, said education department spokesman Will Mantell.

Mantell said the group will ultimately include 30-35 members who will be divided into committees. The city is reaching out to potential members “based on the recommendations of the executive committee and our ongoing discussions with advocates, researchers, educators, parents and community members,” he wrote in an email.

Wiley, the executive board member, said the group wants to bring a diversity of perspectives into the planning process, so will host public meetings in every borough to gather different ideas on school segregation and how to address it.

The group grew out of the city’s “school diversity plan,” which was released this summer after relentless pressure from advocates and recurring headlines about de Blasio’s relative silence on the city’s persistent school segregation. The plan left many advocates underwhelmed.

In particular, they said the city set unambitious racial and socioeconomic integration goals for itself. Pressed on such concerns, Mayor Bill de Blasio told reporters the plan was “a strong first step,” but added: “There will be more to come.”

To some advocates, the advisory group creates an opening to give teeth to the city’s plan.

David Kirkland, executive director of the New York University Metro Center, recently accepted an offer to become a member. He said he hopes — among other changes — to push the city to set more aggressive goals for “racially representative” schools, which the plan currently defines as those where 50 percent to 90 percent of students are black or Hispanic (together those groups make up 70 percent of city students).

“It’s not clear to me that we have the right metrics,” he said. “My hope is that this diversity plan is going to begin to change in significant ways.”

In order for the recommendations to take hold, its members must be truly representative of the community — and free from political pressure to sidestep thorny issues, advocates say.

New York City’s grassroots integration movement has been criticized as being dominated by white middle-class parents and activists, although it includes members of different races and backgrounds. To build broad support for their work, observers say, the advisory group will have to bring in more black and Hispanic families whose children make up the majority of city students — as well as Asian students, who are often left out of the conversation about integration.

“If we don’t have authentic and real representation,” said Matt Gonzales, who lobbies for school integration through the nonprofit New York Appleseed, “then we run the risk of running failed efforts in integration that we’ve already watched unravel” elsewhere.