As Anna Diaz started her sophomore year of high school, simply making it to class each day was an ordeal.

Her home life was sometimes chaotic, her mom was out of work, and she wrestled with depression. On top of that, after a summer of bouncing from hotel to hotel, her family relocated to Queens, lengthening her commute to her Brooklyn high school to nearly two hours. As a result, she rarely made it to first period at Cypress Hills Collegiate Preparatory School, and missed roughly 15 percent of her sophomore year.

“I was going through a lot,” recalled Diaz, now a senior at Cypress Hills. She was hardly alone: That year, 42 percent of her peers were deemed “chronically absent” because they missed at least 10 percent of the school year or about 18 days.

Under pressure to improve attendance, the school has dug deeper into student data, set individual goals for students, reached out to families, and created incentives like trips to museums or theme parks to reward improvement. It’s also tried to make the school more appealing to students — for instance, by establishing a mentorship program that pairs freshmen with older students and working to improve teachers’ lessons — under the theory that students need a reason to show up.

The strategy is paying off: Last school year, 28 percent of students were chronically absent, down from 61 percent in 2014.

“It’s really an overall school approach,” said Principal Amy Yager.

In recent years, New York City’s education department has been paying more attention to chronic absenteeism, which is linked to lower test scores, higher dropout rates, and even a greater risk of entering the criminal justice system. Beyond being a serious risk factor for students, officials see chronic absenteeism as a barometer of a school’s ability to create a safe, stimulating space that entices students to attend.

New York City isn’t alone: Roughly three-quarters of states — including New York — plan to include the measure as one of the ways they evaluate schools under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act.

“If you want achievement every year you have to have attendance almost every day,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a national organization that has pushed for a greater emphasis on absenteeism. New York City, she added, was “one of the first [districts] in the nation to realize they had a problem.”

Under Mayor Bill de Blasio, the city has made improved attendance a central goal of its two most ambitious — and expensive — school-improvement efforts.

Since 2014, the city education department has transformed over 200 schools into “community schools” designed to remove obstacles that can lead to chronic absenteeism — anything from severe asthma and mental health issues, to a lack of clean clothes. The schools were outfitted with medical and dental services, nutrition and fitness programs, tutoring, job training and — in some cases — washers and dryers.

Among them are 94 low-performing schools (including Cypress Hills) that are also part of de Blasio’s $582 million “Renewal” turnaround program, which provides coordinators to manage a host of new support services and tools to track student-level attendance data.

Officials say that broader school improvement efforts — everything from adding evening classes for parents or sending in teacher coaches — should ultimately boost attendance. But they have also zeroed in on specific strategies for drawing students into school.

Community and Renewal schools use customized software that pulls student attendance data out of creaky city databases, allowing school attendance teams to quickly identify which students are racking up lots of absences. Then team members, including nonprofit staffers brought in by the city, visit the homes of chronically absent students, call their parents, or set up counseling sessions.

At P.S. 61 in the Bronx, school officials have started a “walking school bus” where volunteers meet chronically absent students at neighborhood checkpoints then walk them to school. The effort helps students whose parents have health problems or otherwise struggle to drop them off, said Stacey Campo, P.S. 61’s community school director, and “it’s creating some excitement about coming to school.”

City officials have also experimented with sending home postcards that show how many days a student has missed compared to the school’s average. The simple intervention, which the city tried at 52 schools, helped drive down absenteeism, according to Chris Caruso, the education department’s executive director of community schools.

Caruso said that because academic measures like test scores take longer to budge, a school’s chronic absenteeism rate gives an early indication of whether turnaround efforts are taking hold.

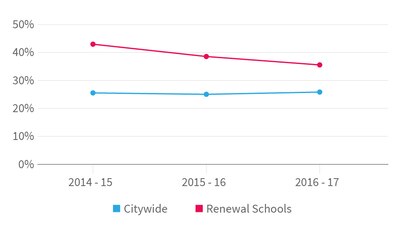

Though the Renewal program has had mixed success raising test scores and graduation rates, the share of students who are chronically absent at those schools has fallen by just under 8 percentage points since 2015. (Still, the schools’ 36 percent chronic absenteeism rate is significantly higher than the 26 percent citywide rate.)

“This is generally a pretty sticky measure that’s difficult to move,” Caruso said, “and we’re seeing real progress.”

In the past, schools had little sense of how many students were missing many days of class.

As recently as ten years ago, most schools focused on the percentage of students who showed up on a given day — known as average daily attendance — not how many days individual students were missing.

That made it difficult to identify students who were gone a few days each month — an easily overlooked occurrence that can balloon into a major problem. It also left schools with a potentially deceptive statistic: A third of students could be chronically absent, yet a school’s average daily attendance could still be 90 percent.

“The entire attendance system was measuring the wrong thing,” said Kim Nauer, the education research director at the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs. “They had no way of seeing whether any individual kid was missing too much school and putting them at risk.”

In 2008, Nauer published a report that was among the first to reveal the scale of New York City’s chronic absenteeism problem. At the time, over 28 percent of students were chronically absent.

Partly in response to the report, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg launched a series of initiatives to combat absenteeism.

The most effective intervention was pairing chronically absent students with “Success Mentors” — school personnel or volunteers who regularly checked in with students and helped coax them back to school. One study found that students with mentors gained nearly two weeks of school on average and were more likely to remain in school three years later. Today, 115 community schools continue to use that approach, a number city officials said would likely increase to 150 this school year.

Under de Blasio, chronic absenteeism has continued on a gradual downward path that began with Bloomberg. Last school year the rate ticked up slightly to 26 percent, but that is still about 2 percentage points lower than when de Blasio took office.

Still, individual schools often struggle to combat chronic absenteeism, which largely stems from forces beyond their control.

At P.S. 211 in the Bronx, for instance, school staffers repeatedly tried to convince a mother with substance abuse issues that she shouldn’t keep her two children at home to help her with laundry and other chores.

“We would make connections with mom and things would go great for a week,” said Jorge Blau, who helps oversee the attendance program, “and then we’d have to start over again.”

Blau, who works for The Children’s Aid Society, a non-profit embedded in the school, said his team was able to help reduce the number of days the students were absent from about 40 down to 20 or so — an improvement, but still a serious threat to their learning.

“Did they come to school more? Yes,” Blau said. “But we didn’t get them over the hump.”