Nearly a month after Carmen Fariña announced that this school year would be her last as New York City’s chancellor, New Yorkers are no closer to knowing who will succeed her.

As city emissaries reach out to possible replacements around the country and City Hall vets people inside the Department of Education, speculation has mounted quickly. Will Mayor Bill de Blasio go with a trusted insider? Or will he try to attract a celebrated outsider who could drum up some excitement about his education agenda?

What’s clear is that de Blasio has committed to picking an educator for the slot, ruling out some officials who have played a leading role in his biggest education initiatives so far. Low pay, an established education agenda, and de Blasio’s reputation for being a micromanager may make it tough to recruit a high-profile outsider. Still, the job remains among the most prestigious education posts in the country.

Everyone who pays attention to education in the city has ideas about who might be under consideration.

After talking to more than a dozen people who keep a close eye on the education department and City Hall, some of them from within, we’ve sorted through the rumors and political jockeying to handicap several contenders.

Alberto Carvalho

Who he is: Carvalho is the widely admired leader of Miami’s school system, where he has spent his entire career. Under his leadership, the district’s finances and academic performance improved. He has an inspiring life story, too: He became an educator after first coming to the United States from Portugal as an undocumented immigrant.

Why you might see him at Tweed: Politically savvy, skilled in engaging with the media, and prolific on Twitter, Carvalho would certainly fill the mayor’s requirement of being able to sell an education agenda. During his tenure, he helped convince county voters to approve a $1 billion bond for school infrastructure and technology upgrades.

Why you might not: Things are going well for Carvalho in Miami, where his contract runs until 2020 — and he’s balked at high-profile opportunities in the past. Like other outsiders, he’s already far outearning the city chancellor’s salary: He makes roughly $345,000 in Miami now, compared to nearly $235,000 for Fariña in New York.

What he says: “My commitment to Miami is so strong and I have demonstrated it in the face of political opportunities,” he told Chalkbeat. “It’s really hard for me to imagine a set of circumstances that would lead to a different decision on my part.”

Kathleen Cashin

Who she is: Cashin is currently a member of New York’s Board of Regents, where she helps set education policy for the entire state. Before that, she spent more than three decades as a New York City educator — first as a teacher and principal before working her way up to be a regional superintendent.

Why you might see her at Tweed: De Blasio has signaled he’s looking for someone like Fariña, and Cashin fits that mold. She believes, as Fariña does, that principals must be veteran educators who earn their autonomy (she resisted Bloomberg’s efforts to hire principals who were not experienced educators). Crucially, she has shown results boosting student achievement in high-poverty areas of the city, a problem de Blasio has struggled to solve.

Why you might not: Cashin recently turned 70, she is not a person of color, and is not likely to bring lots of new ideas to the table.

What she says: Did not respond to a phone call seeking comment.

What a supporter says: “She had the toughest district in the entire city and she handled her district not only with focus,” said Board of Regents Chancellor Betty Rosa, but also “elegance and professionalism beyond belief. I have so much respect for Dr. Cashin.”

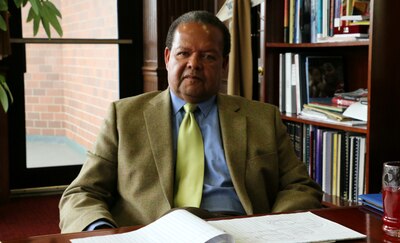

Rudy Crew

Who he is: Crew is the president of Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn, part of the city’s public university system. He previously served as New York City’s schools chief for four years in the late 1990s under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, spent another four running the Miami-Dade county school district, and did a brief (and controversial) stint as an education official in Oregon.

Why you might see him at Tweed: Crew is a black man, which makes him a standout among the education department’s top ranks. He knows the political landscape and has continued to take an interest in the city’s schools through his work at Medgar Evers, where he created a program that provides training to local public-school teachers and early-college classes for students. Crew also seems to share de Blasio’s belief that high-quality instruction should take priority over school integration, and as chancellor, he set up a turnaround program for struggling schools that has clear parallels with the mayor’s Renewal initiative.

Why you might not: While Crew has had some success boosting student achievement, he also has a record of political clashes. He left Miami after the school board’s chair said they had developed “irreconcilable differences” and Oregon amid controversy about his commitment to the job.

What he says: Crew declined to be interviewed, but a spokeswoman said he “has not been contacted about the job.”

MaryEllen Elia

Who she is: Currently the head of New York’s state education department, Elia previously led one of the nation’s 10 largest school districts, Hillsborough County in Florida. There, she gained a reputation for working closely with the local teachers union on policy issues that unions often oppose. She was named Florida’s 2015 superintendent of the year before being ousted by the school board shortly afterward, in a move that garnered some local and national criticism.

Why you might see her at Tweed: While Elia is considered a long shot, it could make sense for de Blasio to give her a look. She’s a good match for de Blasio’s overall orientation: She’s progressive-minded — see the state’s new initiative to help districts integrate their schools — but also believes that schools should be held accountable for helping students learn. Elia has spent nearly three years running the state education department without making enemies. She also hasn’t set out to make a big splash in her leadership, which could be appealing for a mayor whose agenda is already in place.

Why you might not: She appears comfortable in her role in Albany, where she’s helping the state adapt to the new federal education law, and reconsider its approach to teacher evaluations, graduation requirements, and more. Also, she has no experience working in New York City.

What she says: “Commissioner Elia has had no discussions about this,” said State Education Department spokeswoman Emily DeSantis. “She loves her job as State Education Commissioner and remains committed to fostering equity in education for all children across New York State.”

Dorita Gibson

Who she is: Gibson is the education department’s second in command as Fariña’s senior deputy chancellor. She has served at virtually every level of leadership within the New York City school system, rising from teacher to assistant principal, principal, and high-level superintendent. She’s helped lead big changes in the way the education department supports schools, and is partly responsible for overseeing the mayor’s signature “Renewal” program for struggling schools.

Why you might see her at Tweed: She’s already there, an advantage at a moment when some outsiders seem unenthusiastic about taking over the school system. Gibson is one of Fariña’s top deputies who leads initiatives that are core to the city’s education agenda. She’s also a longtime educator, which de Blasio has said is a requirement, and the department’s top-ranking deputy of color.

Why you might not: Despite being Fariña’s number two, Gibson has kept a low profile, and rarely appears in the press. Her absence raises questions about her interest or likelihood of assuming the top position.

What she says: Declined to comment.

What people are saying: Gibson “seems to be a natural successor,” writes David Bloomfield, a professor of education, law, and public policy at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. “The only problem is that, like other central Department of Education officials, she doesn’t seem to have the support of the mayor or chancellor.”

Cheryl Watson-Harris

Who she is: Watson-Harris is the education department’s senior executive director of field support, who is responsible for helping manage centers that support schools on instructional and operational issues. She started her career as a New York City teacher before working as a principal and superintendent in Boston for nearly two decades. She assumed her current role in 2015.

Why you might see her at Tweed: Watson-Harris rose quickly from running just one of the large school-support centers to overseeing all seven. Multiple sources said she was perceived as being groomed for a higher-ranking position at the education education department. And on her Twitter feed, where she acts as a public booster for the school system, she notes that she’s the parent of a student in the city’s public schools.

Why you might not: She would have to leapfrog a number of more senior officials who have years of experience at higher rungs of education department leadership, including Gibson. Insiders question whether she’s ready to make that jump.

What she says: Declined to comment.

Phil Weinberg

Who he is: Weinberg is one of Fariña’s six deputy chancellors. He began his career teaching at Brooklyn’s High School of Telecommunication Arts and Technology — and wound up staying for 27 years before rising to principal in 2001. In 2014, Fariña plucked him from that post to head up a resurrected “teaching and learning” division that had been dormant for years.

Why you might see him at Tweed: Weinberg is widely respected among educators and has avoided major blowback during his four years leading teaching and learning at the department. The things he’s passionate about — including strong teaching, coherent curriculum, and collaboration among educators — are close to Fariña’s heart, which would matter if she plays a strong role in choosing her successor.

Why you might not: His efforts have been peripheral to the initiatives the de Blasio administration cares about most, such as prekindergarten and community schools. He seems to prefer an internal role to a public-facing one. And he’s a white man — hardly the top demographic choice for the leader of a district where more than 70 percent of students are black or Hispanic.

What he says: Did not respond to a message seeking comment.

That’s the short list, but many other names have also surfaced.

Josh Starr, a former New York City official who now works at PDK International, and Pedro Noguera, a professor at UCLA, would make good fits for de Blasio’s progressive platform, but both have said they are not in the running.

Other names that have been floated as potential contenders include Lillian Lowery, a former district superintendent and top education official in Maryland and Delaware (now a vice president at Ed Trust); Angelica Infante-Green, a fast-rising deputy commissioner in New York’s state education department who is reportedly in the running for Mass. state education commissioner; and Betty Rosa, a former superintendent in the Bronx and chancellor of New York’s Board of Regents.

There’s also a cadre of educators who have left New York City for other school systems and might be interested in returning, including Andres Alonso, currently an education professor at Harvard, and Jaime Aquino, who helps lead New Leaders for New Schools, a non-profit organization that focuses on training principals.

Philissa Cramer and Christina Veiga contributed reporting.