New York City schools are suspending students significantly more often, according to new data the city released Friday.

Between July and December 2017, schools issued roughly 14,500 suspensions — 21 percent more than in the same period the previous year. The increase reverses a multi-year trend of precipitously declining suspension rates.

Principal suspensions, which are handed out for less serious offenses, increased by 19.5 percent. Meanwhile, more serious superintendent suspensions shot up by nearly 25 percent.

Education department officials did not answer questions about why the suspension rate had increased. (The new data, which the department is required to publish, was released on outgoing Chancellor Carmen Fariña’s last day.)

But city officials suggested the increase could be more muted by the end of the school year, partly because they have worked to expand trainings in light of the increase. If the entire school year to date is taken into account through mid-March, officials noted, the suspension rate is up a more modest 5.4 percent compared to the same period in the 2016-17 school year.

They pointed out that just 37 students in grades K-2 were suspended in the first half of this school year — an 85 percent decrease that comes after the city revised the discipline code to make it much more difficult to suspend the city’s youngest students.

The city also said more specific efforts to change discipline practices had paid off with reduced suspensions, particularly in Brooklyn’s District 18.

“Schools must be safe havens for communities and we are continuing to carefully review and monitor suspension data to provide targeted interventions,” Elizabeth Rose, a deputy chancellor, said in a statement. “This remains a top priority, and we are expanding school-based supports and resources while remaining vigilant in addressing the root causes of conflict.”

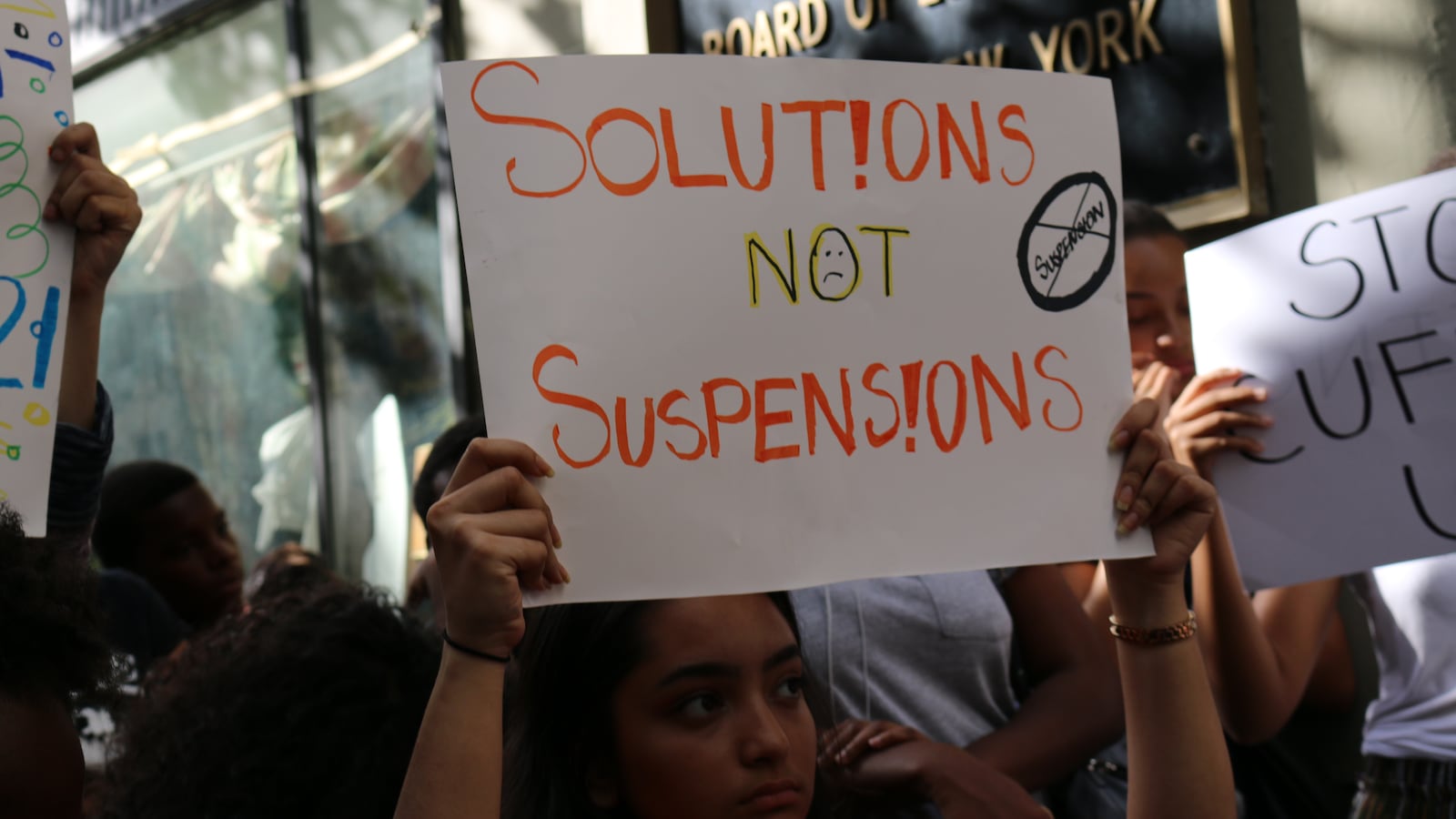

The city has joined many others in working to reduce suspensions, which disproportionately affect students of color. Mayor Bill de Blasio has championed policies that make issuing suspensions more difficult, and the education department has started requiring central signoff for suspensions for certain infractions. The city has also invested in training staff members to provide alternatives to suspensions, something that community advocates have asked for. Overall, suspensions have fallen 34 percent over the past five years.

The city’s new discipline policies have not been universally popular. Some union officials and educators have complained that limiting schools’ ability to suspend students without proper training in alternative approaches has made schools more chaotic and dangerous, an assertion that is at least partially backed by student and teacher surveys. And even advocates who support the changes have raised concerns that the city has not done enough to train educators on what to do instead.

The latest numbers could suggest that schools are in fact experiencing more problematic behavior — but backlash against the discipline reforms could also be a factor.

The more recent spike in suspensions also comes amid a series of school safety problems, and could provoke a new round of criticism of de Blasio’s school discipline policies. In September, a student stabbed two of his peers — one fatally — at a Bronx high school, the first student to die at the hands of another inside a school building in over two decades. City officials acknowledged Friday that major crimes in city schools ticked up during the the fourth quarter of 2017, but they said those crime had fallen back down in recent months and are down 28 percent over five years.

The new data do not include student demographics. The most recent reports that include racial data show that while 27 percent of city students are black, they accounted for about 47 percent of all suspensions.

The education department also reported that students were taken away by emergency medical personnel due to an emotional or psychological condition 547 times from last July through December, up 13 percent compared with the same period the previous year. Overall, the number of times students were transported from schools by EMS for any reason ticked up 6 percent to 4,554.

Advocates have repeatedly criticized the practice of calling 911 to handle disorderly students, and a 2014 settlement barred schools from making 911 calls before trying to defuse the situations themselves.