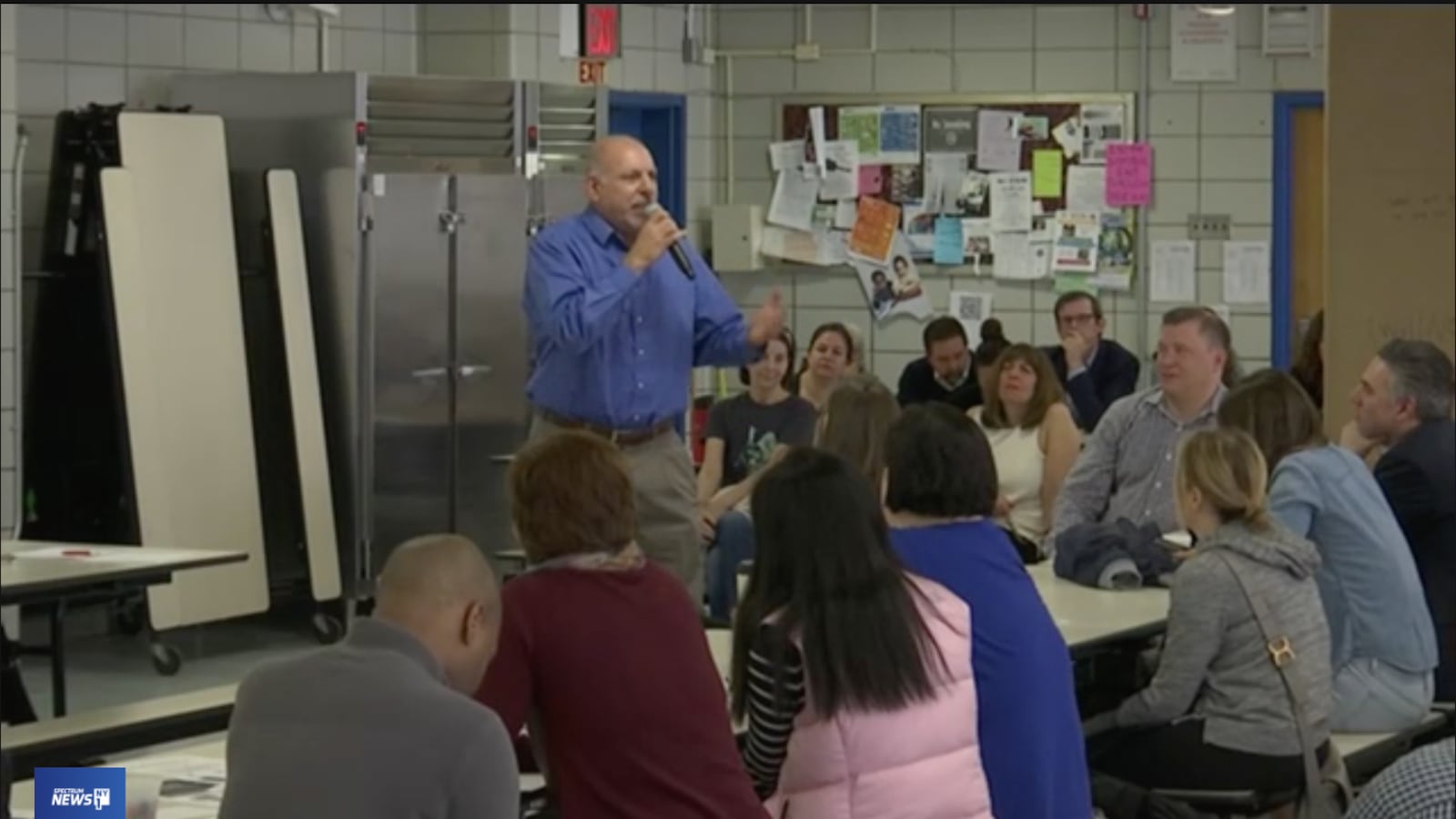

Video of last week’s heated meeting about a Manhattan school integration plan went viral in part because of the angry parents, and in part because of Henry Zymeck.

The principal at one of the affected middle schools, Zymeck took the mic and forcefully stood up for the plan, which would make it easier for students with low test scores to earn seats in sought-after schools.

“There are kids that are tremendously disadvantaged,” he said. “To compare these students and say, ‘My already advantaged kid needs more advantage! They need to be kept away from those kids!’ is tremendously offensive to me.”

The comments have won praise from Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza — who said he was “proud of the principal in the video who spoke out about what equity really means” — and prompted questions about Zymeck himself.

Zymeck has led the Computer School for about a dozen years, building a relatively diverse (and popular) middle school in a district divided by race and academics. He and other principals, such as Marlon Lowe at Mott Hall II, have played an unusually public role in trying to build buy-in for the proposal across District 3, which stretches from the Upper West Side into part of Harlem.

“Whether it’s based on academics, on race, on economics — segregation is bad for kids,” Zymeck said. “When we’re a family, we try to look out for the best interest of all kids, not just the ones in our households. And that, to me, is what public education is about.”

Zymeck has spent his 26-year teaching career entirely at the Computer School, becoming an educator later in life after working on Wall Street and as a legal assistant. He grew up in the Northeast Bronx and attended public schools in the city. Since the footage of Zymeck spread online, he said he has gotten an enormous amount of feedback — mostly positive — from the likes of random strangers and former students. But he has become a reluctant center of attention.

“This is not about me,” he said, repeatedly noting the work of other principals in the district. “I really just want to do right by the kids in our district.”

Chalkbeat caught up with Zymeck to ask about the proposal and his response to the pushback. Here’s what he had to say about how schools can serve all students well and why principals like him have taken a leading role.

Why he believes in academic diversity

In District 3 and across New York City, middle and high school students are often sorted into schools based on their academic performance. Schools where most students struggle academically also often face more of the challenges that come with poverty.

Zymeck said that the proposal would help even the playing field and also benefit students.

“There are those who feel very strongly committed to what I’ll call homogeneous grouping in education … on both ends of the spectrum, that you can serve kids best when you divide them up by test scores,” he said.

But research, and his own experience, have convinced Zymeck otherwise.

The Computer School selects its students, and it offered 19 percent of its seats to students who scored just below the state’s standards in reading and math last fall. Under the plan the school would likely take in more students whose scores were in the very lowest tier.

Zymeck said that students who struggle on standardized tests often offer other strengths that benefit the classroom.

“Sometimes it’s the kid with the lowest test score that is the peacemaker, or is the artist, or is someone who has a photographic memory that plays into the group work,” he said.

On whether all schools are ready to serve more needy students

Some local parents have raised concerns about whether schools will get extra resources as they adapt to serving more struggling students. Will the changes water down instruction? Will higher-achieving students get ignored?

It’s “valid” to wonder how schools will serve all students well, Zymeck said, but he also worries those questions suggest some students are just less capable than others.

“I think that our school and its history has demonstrated that not only is the curriculum not watered down, it’s enriched,” he said.

Zymeck said it’s the job of principals and teachers to find ways to meet the needs of all their students, and to set high expectations for everyone.

“We can’t make excuses about why kids do and don’t achieve,” he said. “The culture of the school needs to match the students, not the other way around.”

Zymeck compared the logistics of the District 3 proposal to citywide changes over the last several years requiring schools to serve a more equitable share of students with disabilities — an effort he thinks has been very successful.

“I think it starts with the commitment to do it,” he said.

On the role of principals

Principals have been front and center when it comes to developing and supporting the academic integration plan in District 3. It was drafted in response to city changes to the middle school admissions process, which school leaders felt would only exacerbate segregation.

“Part of our job is also to educate the parent community, and I think it’s important for the parent community to not just accept what we’re saying out of hand, but to hear us and to listen with an open mind, and to trust that we deeply care about their kids,” Zymeck said. “But we deeply care about all kids in the district.”

While most school leaders agree on the need to act, the final details of the plan are still being debated. For instance, principals at K-8 schools want to make sure they can retain the students they’ve served since elementary school, he said.

“There is a general consensus among my colleagues,” he said. “It’s not perfect, but it’s close enough that I feel comfortable moving forward with the plan as it stands.”