To Kelly Bare, a Brooklyn mom who chose her neighborhood school when many others like her would not, the proposal currently dividing Manhattan parents merely tinkers at the margins of much bigger problems.

That proposal would change admissions rules at middle schools in District 3, which includes the Upper West Side and some parts of Harlem, so that more students with low test scores get into the most sought-after schools.

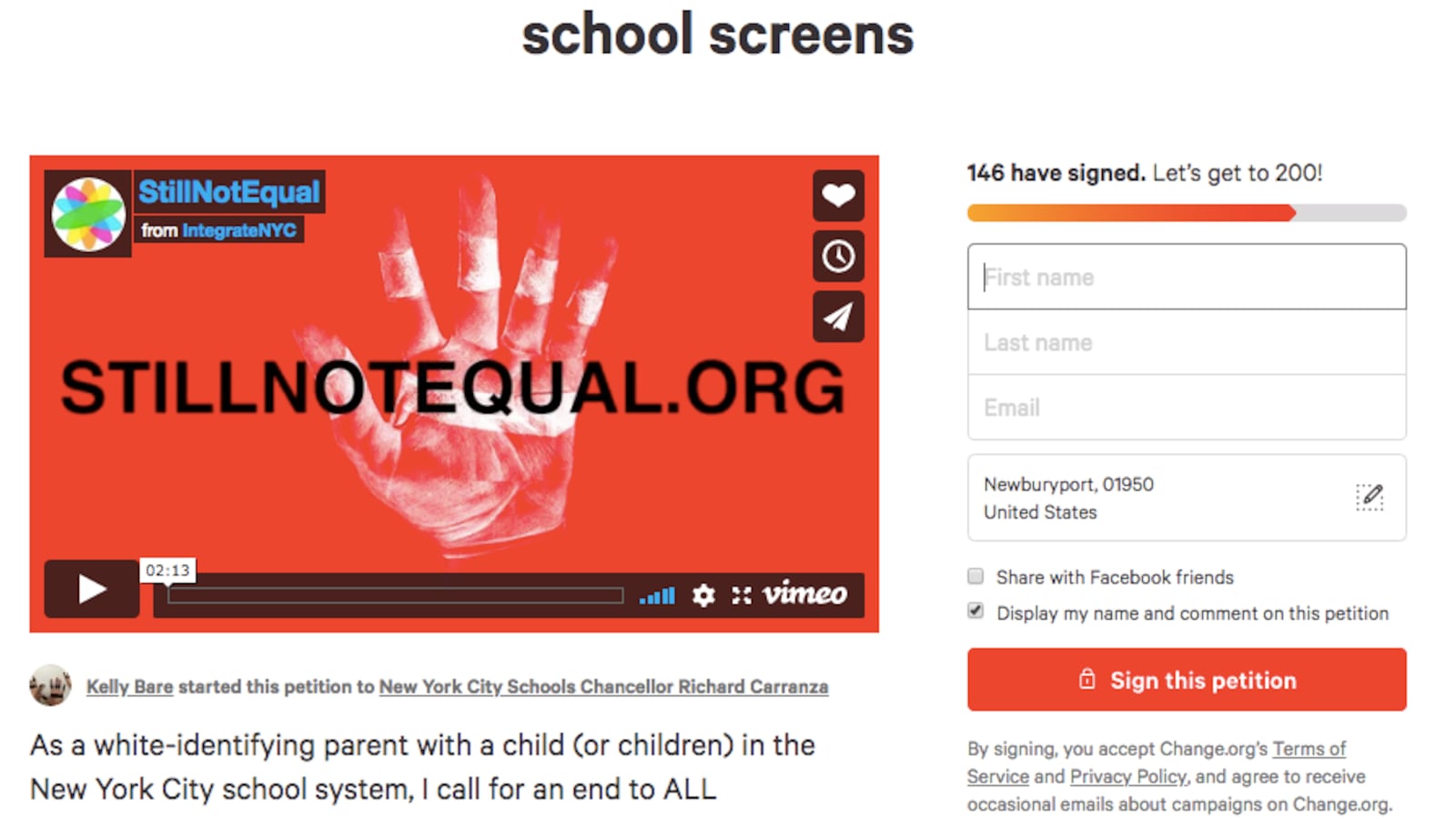

But it wouldn’t stop schools from screening students for academic ability — so Bare sat down to petition Chancellor Richard Carranza to make a more sweeping change.

“It is past time to end the use of all middle-school enrollment screens (except those designed to identify extraordinary talent in the arts) system wide,” Bare wrote on a petition she started Tuesday on Change.org. “These screens systematically isolate and exclude students of color, and must be removed.”

Bare set a pair of modest goals: “to put out an antidote to some of the ugliness that’s out there,” she told Chalkbeat, and to have 100 “white-identifying parents” sign the petition.

A day later, she was closing in on that target and contemplating what to do next. The options, she said, include raising the bar (it’s now at 200) and figuring out how to show Carranza that plenty of his constituents would endorse changes like the ones being considered in District 3.

“We need to let him know that he has some political cover,” Bare said. “These apocryphal white parents who are going to pack up and move — maybe there aren’t as many of them as they think. Someone needs to come forward and say, ‘I have your back. Keep going.’”

Bare has long been a public face for white parents choosing schools where their children would be in the minority. In 2013, the New York Times profiled her as part of a story about a particular dynamic in the city’s real estate market: that of middle-class white families who are deciding how much to prioritize schools when buying apartments, and then whether to use local schools when they move into gentrifying neighborhoods.

Bare and her family bought an apartment in Crown Heights where the local school was deemed “persistently dangerous” and posted very low test scores. “We knew we could not afford to buy that kind of space in a zone where the schools were already proven,” she told the newspaper at the time. “We took a calculated risk — buying an apartment that we loved, on the edge of a neighborhood that we loved, in an area we presumed would change fairly rapidly.”

Five years on, Bare estimates she spends three quarters of her working hours advocating for integrated schools like the one her two children currently attend — P.S. 705, which replaced the neighborhood’s original school after the city closed that one. She’s building a diversity committee on the school’s PTA; founded a group called Live Here, Learn Here aimed at growing support for schools in her district; and participates in citywide and national coalitions working to combat racism in public schools.

Nearly 20 percent of students at P.S. 705 are white, according to city data, and about a third come from families affluent enough not to qualify for subsidized meals — making it a diverse option in Crown Heights. That’s in no small part due to the community’s advocacy — it was one of the first schools to ask the city for the right to reserve a fifth of spaces for immigrant students and children involved in the foster care system under a new diversity initiative.

“I believe that schools can be transformational because it was for me,” Bare said.

Online petitions frequently have little practical impact beyond allowing people to elevate perspectives that might otherwise be left out of public debates. But sometimes they can make a big difference. The city teachers union right now is lobbying for paid parental leave for its members, for example, after a petition to make that a top priority went viral last year.

Bare said she hopes her petition helps change the conversation in New York City in a similarly seismic way. “Individuals need to make different choices but policy needs to change as well,” she said.

And the petition offers a clear suggestion for what should happen first.

“These screens, which are just one mechanism leveraged to protect and maintain the racial segregation of the city’s public schools, could be removed with a stroke of a pen,” the petition reads. “Chancellor Carranza, you could make this move tomorrow.”

If he does not, Bare said her family will not seek admission at screened middle schools next year when her son is in fifth grade. The middle school admissions process, she says, is steeped in the same troubling racial dynamics that she has devoted her energies toward dismantling.

“My kids would be fine wherever they go to middle school,” she said. “My child is not going to be thrown away and I know that, and that’s a privilege.”