Fifty years ago, 19 letters forever altered the course of New York City’s public schools.

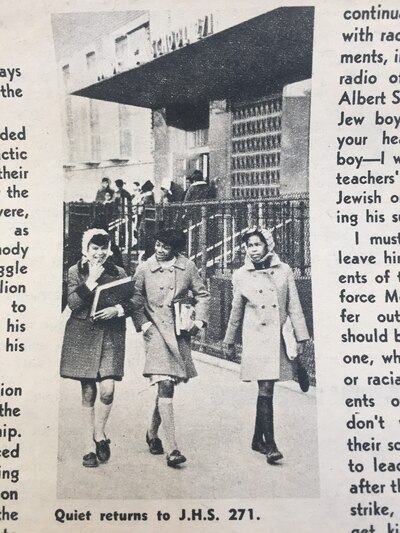

On May 9, 1968, the community school board in Ocean Hill-Brownsville sent termination letters to 19 educators, most from J.H.S. 271 — setting in motion a chain of events that would lead to bitter teachers strikes and eventually a total reorganization of the nation’s largest school system.

“I think it’s fair to say this is the spark,” said Nick Juravich, a postdoctoral fellow at the New-York Historical Society who has studied the teachers’ dismissal. “This is when what has been a simmering conflict becomes an actual confrontation.”

At the core of that conflict were themes familiar to New York City schools today — racial tension, battles over who should control the schools, and fights over teachers’ rights — but with much higher stakes.

On the heels of failed integration efforts in the 1960s, communities of color — distrustful of the city’s centralized education bureaucracy and frustrated with schools’ poor performance — had spent several years pushing for local control of their schools. By 1967, they had a broad base of support, including Mayor John Lindsay and editorial boards.

“The present system has been failing our children for too long,” a WABC “radio editorial” said in 1967. “The [decentralization] plan has its risks — but it also has one great advantage: It gives the city’s parents a genuine opportunity to do something about their children’s education.”

To test the idea, the city created experimental community school boards in three neighborhoods, including Ocean Hill-Brownsville. But it quickly became clear that the union and local boards had different ideas of what constituted local control.

In May 1968, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville board asserted its newfound strength by dismissing the 13 teachers and six administrators, who were allegedly not on board with neighborhood’s decentralization project. Adding to the tension, the majority of the dismissed educators were white. The move caused chaos, as the central Board of Education told the educators to ignore their dismissal notices and return to work.

It also enraged city union leader Albert Shanker, who said the teachers were victims of “vigilante activity” who had been denied due process, according to a New York Times story from the time.

A piece written by a representative of the United Federation of Teachers called the firings “illegal,” the argument for them “a cruel hoax,” and suggests that much of the animosity towards the teachers is being “controlled by a small group of militants.”

The event set the stage for racially charged conflict between the mainly white and Jewish teachers union and the predominantly black and Hispanic Brooklyn neighborhood. For instance, a black teacher went on the radio and recited a student poem with a Jewish slur, an incident the unions publicized, according to a Daily News story from 2017.

Here’s how the Times would later describe what happened next:

By fall, that dispute had escalated into citywide strikes to protect, the union said, the contractual rights of teachers. Adding to the heat, in a year when there were race riots around the nation, was the fact that a largely white teachers’ union and a predominantly white central power structure were pitted against a black and Puerto Rican community. An uneasy truce finally sent teachers back to work in November.

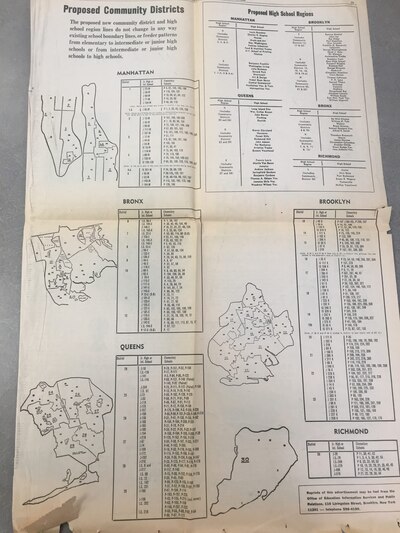

Out of the ashes of the conflict, a new state law required the city’s education department to put together a full decentralization plan. A sprawling map printed in the New York Times in December of 1968 shows some of the first depictions of the school system split into 30 school districts.

The new structure, finalized in 1970, would eventually divide the city into 32 districts with control of the elementary and middle schools, while high schools remained under the control of a central system.

Juravich said that the plan did not satisfy many black and Hispanic parents, since the new districts were too large and lacked certain controls over the hiring of teachers. The boards also became hotbeds of corruption — used to “turn many districts into pork barrels and political bases,” as the Times would later describe.

That structure, of course, did not last forever. In 2002, Mayor Michael Bloomberg convinced the state legislature to grant the mayor control over city schools. While the city is still divided into 32 community school districts, local school boards no longer have much sway over how schools are run.

The Brooklyn middle school, J.H.S. 271, was closed for poor performance in 2008. Today the building houses Eagle Academy for Young Men II, Mott Hall IV, and Uncommon’s Ocean Hill Collegiate Charter School.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that Juravich said the new districts were too large, not too small.