When Emmanuel Ruiz cracked open the city’s 600-page high school directory, he was in search of a school with a strong academic track where he could pursue math and technology. After careful consideration, the promising Brooklyn student selected his 12 favorites.

But when he handed the list to his advisor at Bridge to Enter Advanced Mathematics — a program for students interested in becoming scientists, engineers, and computer scientists — she immediately spotted a problem.

One of the schools on Ruiz’s list was Eleanor Roosevelt, which almost exclusively enrolls residents from Manhattan’s District 2, one of the most affluent school districts in the city. Ruiz, who lives in Bedford-Stuyvesant, had virtually no shot at attending because of where he lived.

“I was very confused and angry because I was trying to put down as many good schools as possible,” said Ruiz, who is now a sophomore at Manhattan Village Academy. “I thought, now it’s going to be hard to find another school that I really like.”

A charged debate about New York City’s elite specialized high schools, which admit students based on a single test and enroll a low share of black and Hispanic students, has blown open in recent days after Mayor de Blasio proposed changes to their admissions process. But the laser focus on these eight schools leaves out hundreds of other schools and programs across the system whose policies also segregate students by race and class.

The exclusivity starts in elementary school, with gifted and talented programs, and runs through middle school, with highly selective screened programs. By the time students get to high school, about one third of the city’s more than 400 high schools pick students based on grades, test scores, interviews, auditions, or other factors.

But critics say the rule Ruiz encountered in Manhattan’s District 2 is particularly frustrating because it excludes large swaths of students, even if they have excellent academic records. The district, which spans the wealthy neighborhoods of the Upper East Side, SoHo, and TriBeCa, is home to six sought-after and highly selective high schools, all of which have near-perfect graduation rates.

But while most of the schools receive thousands of applicants a year, they give preference to students who live or attend school inside the relatively affluent district, meaning the most popular options rarely have room for students from surrounding, less wealthy neighborhoods. For instance, at Eleanor Roosevelt, 100 percent of offers last year went to students or residents from District 2 and at Baruch, 98 percent of offers did. The rule, critics say, seriously undermines the idea that students can apply to any high school in the city regardless of their ZIP code.

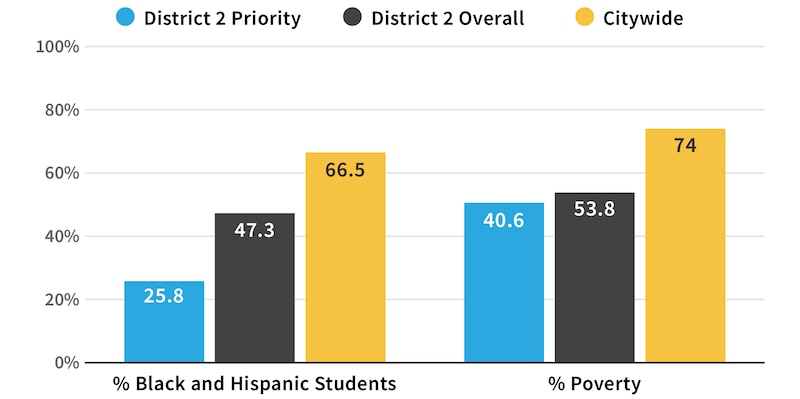

This set of schools is also significantly more likely to exclude black, Hispanic, and poor students. At schools with the District 2 admissions preference that are highly selective, 26 percent of students are black or Hispanic compared to 47 percent in the district as a whole and 67 percent citywide. Similarly, only 41 percent of students at these schools live in poverty compared to 74 percent of overall city students.

Supporters of District 2’s geographic priority argue that different types of geographic priorities exist in communities across the city because it is important to have neighborhood schools. Others say that removing the priority status would benefit very few students and fail to put a true dent in a deeply segregated school system — but it would anger a group of well-connected middle-class parents. These advocates say the real cause of the unequal system is not a single priority status at the six schools, but rather allowing schools to select students by ability in the first place.

But the policy is confounding to those who work with high-achieving students from low-income areas in other parts of the city.

“It seems illogical that a district that already has such a wealth of resources is preventing students from lower-income areas from getting into these great high schools,” said Lynn Cartwright-Punnett, Ruiz’s advisor at BEAM. “From a big picture, what’s best for all children perspective, this doesn’t make any sense.”

***

The geographic priority in District 2, experts say, grew out of an attempt by officials to attract more middle-class families to public schools after years of decline in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

These families, officials reasoned, could draw resources into a system badly in need of a turnaround. In order to attract them, officials in District 2 started creating new alternative school options, said Jacqueline Ancess, who was the director of educational options in District 2 at the time and now runs a research center at Teachers College, Columbia University.

“Middle-class families in the public school system were at a low and this definitely brought more middle-class families into the schools,” Ancess said.

Throughout the 90s, more middle-class or affluent families started to enroll their children in Manhattan’s public schools. But when they reached high school, these families hit a snag: there were not enough high-quality options in the district, said Clara Hemphill, the founder of the school review site InsideSchools.

“There was a general sense that the high schools that were controlled by central were not offering kids the chance for a college prep curriculum and honestly weren’t even safe at the time,” Hemphill said.

The community school board in District 2 decided to take matters into its own hands and create high schools for students in the district.

One such school was Eleanor Roosevelt, which Upper East Side parents — and then city councilmember Eva Moskowitz, now the CEO of Success Academy charter network — pushed for. The debate was racially charged even back in 2001 when the school was approved. Upper East Side parents wanted an even more restrictive school zone that would have included families that lived east of Central Park between 59th and 96th streets. But officials feared that, since the population in those neighborhoods was overwhelmingly white, the plan would be challenged by civil rights groups, according to a New York Times article.

Not long after, Mayor Michael Bloomberg decided to turn the entire high school admissions system on its head. In 2003, the administration decided students would no longer have access to a neighborhood high school they could attend by default. Instead, all students would apply to up to 12 schools and get matched to one.

But beneath this system of school choice, the city preserved a series of admissions rules that allowed students in certain areas of the city to have a leg up in admissions at schools in their neighborhoods. Some gave preference to students who lived in boroughs, districts, or even within particular streets.

Many of those priorities have survived until today — including preference in District 2. By the city’s count, there are 50 high schools that prioritize in-district students, a number that includes schools that specify students must live within certain streets. There are also an additional 28 zoned schools that set aside some seats for students from surrounding neighborhoods. These schools vary dramatically in selectivity and popularity.

Eric Nadelstern, who served as deputy chancellor for the education department during the Bloomberg era, said that it wasn’t a top priority to get rid of geographic preferences when Bloomberg revamped high school admissions. That’s partially because their model of school change required keeping middle-class families in the schools, he said.

“Their goal was to retain the middle class and this was their strategy for doing it,” he said. “I think where we erred was that we created an even more segregated school system.”

***

Years later, the education department has still not changed its stance on District 2 priority or many other geographic priorities, though officials did not rule out changes in the future.

“School communities should be inclusive learning environments that are representative of New York City, and we’re continuing to look at ways to make the high school admissions process fairer for all families in District 2 and across the City,” said education department spokesman Douglas Cohen.

Education department officials also noted that the schools have historically prioritized in-district students because there are no zoned high schools in Manhattan.

Even the principal at Eleanor Roosevelt High School, Dimitri Saliani, seems open to the discussion about how to change admissions in the city.

“I am in full support for the continued conversation of how we can address important issues related to admissions,” Saliani wrote to Chalkbeat in an email.

Several advocates and parents say that while the city’s high school admissions system needs to be overhauled, eliminating District 2 priority is not the way to do it. For instance, Nadelstern argues that tackling District 2 priority early on in a broader plan to desegregate schools could backfire and cause middle-class parents to pull their children from the public school system.

“What you can’t do in a city like New York is throw down the gauntlet in front of a politically powerful, organized parent group and expect to retain middle-class participation in the public schools,” Nadelstern said.

Other critics argue that geographic priority like that in District 2 isn’t the largest culprit in the stratified school system — sorting students by ability is. At many of these schools, even with the priority given in the district, students need near-perfect grades and test scores to earn admission. Since selective admission tends to favor affluent white students, nothing major can change until this “screening” mechanism is tackled, said Shino Tanikawa, vice president of the District 2 Community Education Council.

Eric Goldberg, another member of District 2’s Community Education Council, who is also the parent of a seventh-grade student, said he understands the benefits of having some neighborhood high schools, including having a community hub and lessening the travel burden for students. Goldberg agrees with Tanikawa that changing admissions at this small number of schools is not likely to make a major dent in school diversity without an overhaul of other admissions criteria.

“If we’re looking at this through a lens of diversity and integration,” Goldberg said, “I’m confident that we’re not looking in the right place.”

But to advocates and those who work with students in areas like the Bronx and Brooklyn — where many would have a short commute to some of the most coveted schools but can’t get accepted due to the geographic rule — these explanations ring hollow. In a system built on school choice, giving students from every neighborhood a chance to attend the best schools in the city seems like a no-brainer to Maurice Frumkin, a former city education department official who now runs an admissions consultancy.

“You can’t have it both ways,” Frumkin said. “If you’re creating a truly equitable process, you can’t say, ‘Well, we’re creating a choice process and allowing families to apply anywhere they want … but by the way, we’re not truly allowing families to do that.”

In the meantime, students like Ruiz are being blocked from the schools based on their home ZIP code. Before he knew about the rule, Ruiz said he assumed that the population of a school uptown in Manhattan would be different than where he lives. But the admissions process made him feel like he wasn’t welcome there, he said.

“I’m just not fit to go to that school,” he said he realized. “It did come across as very unfair. I don’t think it should be like that.”

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that Shino Tanikawa is the vice president, not the president, of the District 2 Community Education Council.