This story about early reading instruction is part of a series about innovative practices in the core subjects in the early grades. It was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

BRONX, N.Y. — The end of third grade is a turning point for young readers; it’s where skilled readers take off, finally able to competently read a variety of texts, and struggling readers teeter off track, often unable to ever catch up. This crucial juncture, and its far-reaching implications for those who don’t meet the mark, is why some educators are focusing their literacy efforts on the school years that come before third grade — hoping through innovation to offset what could be a terrible and lasting deficit in children’s reading skills.

Last year, in tests of the nation’s public school fourth graders, just 23 percent of Hispanic children and 20 percent of African-American children scored “proficient” in reading. Among low-income students in general, just 22 percent of fourth-graders were proficient readers. The repercussions of not learning to read are magnified for poor children: Research shows that low-income children who cannot read at grade level by third grade are six times more likely to become high school dropouts.

“In this country, we have the ability to get 90 to 95 percent of kids reading successfully — if only we’d implement scientifically based methods,” said Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, a think tank that advocates tougher teacher evaluation. “Yet we routinely only prepare between 60 and 70 percent of kids to be successful readers.” Teacher-prep programs, she added, bear a large part of the responsibility here: Many teachers-in-training receive just one course in how to teach reading — a teaching task which experts agree is extremely complex — before heading into the classroom.

“It’s a source of deep frustration for a lot of people, including myself, that we fail to adequately prepare teachers to teach reading,” Walsh said. “It’s simply malpractice.”

Children do not come wired to learn how to read: It is an acquired skill. A teacher must be able to synthesize a deep well of research, master a variety of instructional methods and then be able to deploy this knowledge daily to meet each child at his or her own reading ability level.

At P.S. 218 in the Bronx, a high-poverty public bilingual school where nearly 90 percent of the students are Hispanic and 32 percent are English language learners, early-grade teachers have spent the last three years learning how to do a better job of teaching students to read — and they are seeing results.

Related: One reason so many kids in Mississippi fail reading tests?

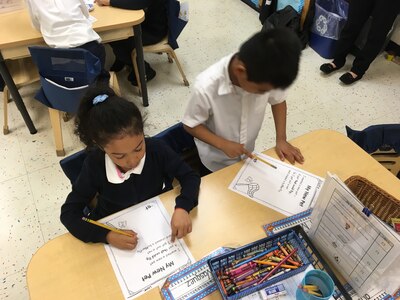

On a recent spring day, 16 kindergarteners, some sitting on small chairs, others cross-legged on foam mats on the floor, trained their eyes on a large yellow easel pad. Miss T., known outside the classroom as Rosy Taveras, tapped a hand pointer below each word on the pad as, together, they read aloud:

“My New Pet

I wanted a new pet.

A pet that could fly.

So I got out a net

and chased a butterfly.”

Taveras showed flashcards with the words “OUT” and “SO” spelled in large block letters.

“Gimme an O, gimme a U, gimme a T! What’s that spell?” she asked, cheerleader-style.

“OUT!” yelled her students.

“Take a look at these cards,” Taveras said. “Now turn to your neighbor and ask: ‘How did you know it was ‘HOW’ or ‘SO’?’”

The students mumbled to each other for several seconds.

“Now I need a friend to find ‘SO’ and ‘OUT’ in the poem,” Taveras said. Small hands shot up. “Ephraim, you’re up.”

This is shared reading, a finely-tuned teaching practice that offers Taveras the opportunity to model fluent and expressive reading while her students join in. If the practice is done well, kids will feel like successful readers, and be eager to learn more. Although Taveras is the teacher in charge, she is closely monitored by reading coach Xiania Foster, who provides feedback after each chunk of the daily reading lesson.

Taveras has been a teacher for four years, all of them at P.S. 218. “When I went to college [to study teaching], they tell you: ‘Here, this is the lesson plan for reading, for math, etc.,’ but once you get to the classroom, you realize there’s no way this is going to cover everything,” she said. “You can’t just go black and white. You have to differentiate for each student, and always keep in your mind: what movement can I do for the students who don’t know the language, what visuals can I bring so they have a better understanding of the lesson? These are not things they teach you in college.”

Foster, Taveras’ instructional coach, has been coming to P.S. 218 for three years, part of a partnership between the school and Early Reading Matters, a teacher-training program. ERM focuses on showing public school teachers who work in New York City’s high-poverty schools how to skillfully get students in the early grades to read at grade level. The program is currently working in 32 schools in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan, with plans to expand to 62 schools by 2021.

So far, results are promising. Averaged across 15 schools during the 2016-17 school year, the nonprofit reports an approximately 11 percent boost in the number of students reading at grade level — from 33 percent reading at grade level in the fall to 44 percent by the beginning of summer. The figures do not include students who missed more than 28 days of class each year.

The program is research-based, said Lynette Guastaferro, chief executive officer of ERM’s parent company, Teaching Matters. If teachers hope to create eager readers, especially among kids who struggle to learn the skill, their chances of success will be far greater if key principals of balanced literacy become second nature, an essential part of their teaching practice. These techniques include how to create strong, guided reading instruction, how to select and appropriately use high-quality texts, and how to assess each child’s reading level to better target guided and independent reading.

Related: Can Common Core reading tests ever be fair?

When Sergio Cáceres became principal of P.S. 218 four years ago, he decided to focus on the school’s youngest students. “If you want to have an impact in the later grades, you need to start with K to 2,” he said. “That’s the foundation of learning.”

After an initial assessment, he determined that early reading instruction was one of the school’s glaring weaknesses. “We have very good teachers but they did not know how to teach reading,” Cáceres said.

In 2014, Cáceres’ first year at the school, just 19 percent of the students tested as proficient on the statewide English Language Arts test, compared to 31 percent statewide. “Early literacy is difficult to teach well, especially when it comes to teaching students who are struggling readers, and unfortunately, it’s a skill teachers don’t come prepared with,” said the principal. “Especially so for kindergarten through second grade.”

Without high-quality and targeted support, research shows, many teachers decide to quit. The rate at which teachers leave the profession — generally about 8 percent nationwide — is 50 percent higher at high-poverty schools and 70 percent higher in schools serving primarily students of color. At P.S. 218, almost 40 percent of teachers have less than three years’ teaching experience.

When the district superintendent asked P.S. 218 to consider implementing the ERM teaching model, Cáceres didn’t hesitate, even though it would clearly mean extra hours and effort for Cáceres and his already overworked teachers. He appreciated ERM’s research-based approach to teaching reading and he was also swayed by the financials: Normally, hiring a reading coach would cost approximately $1,250 per day, but ERM training and three years of in-school coaching won’t cost the school a penny; it is all funded by grants. In addition to the ERM training, the school received a Universal Literacy Coach, part of New York City’s Universal Literacy Initiative, a citywide effort to get 100 percent of all second-graders reading at grade level by 2026.

“So we worked to align Early Reading Matters with the U.Lit coach and, wow, what a powerful combination,” said Cáceres. “It was very rigorous.”

Related: Four tips from a high-poverty school where kindergarteners excel at reading

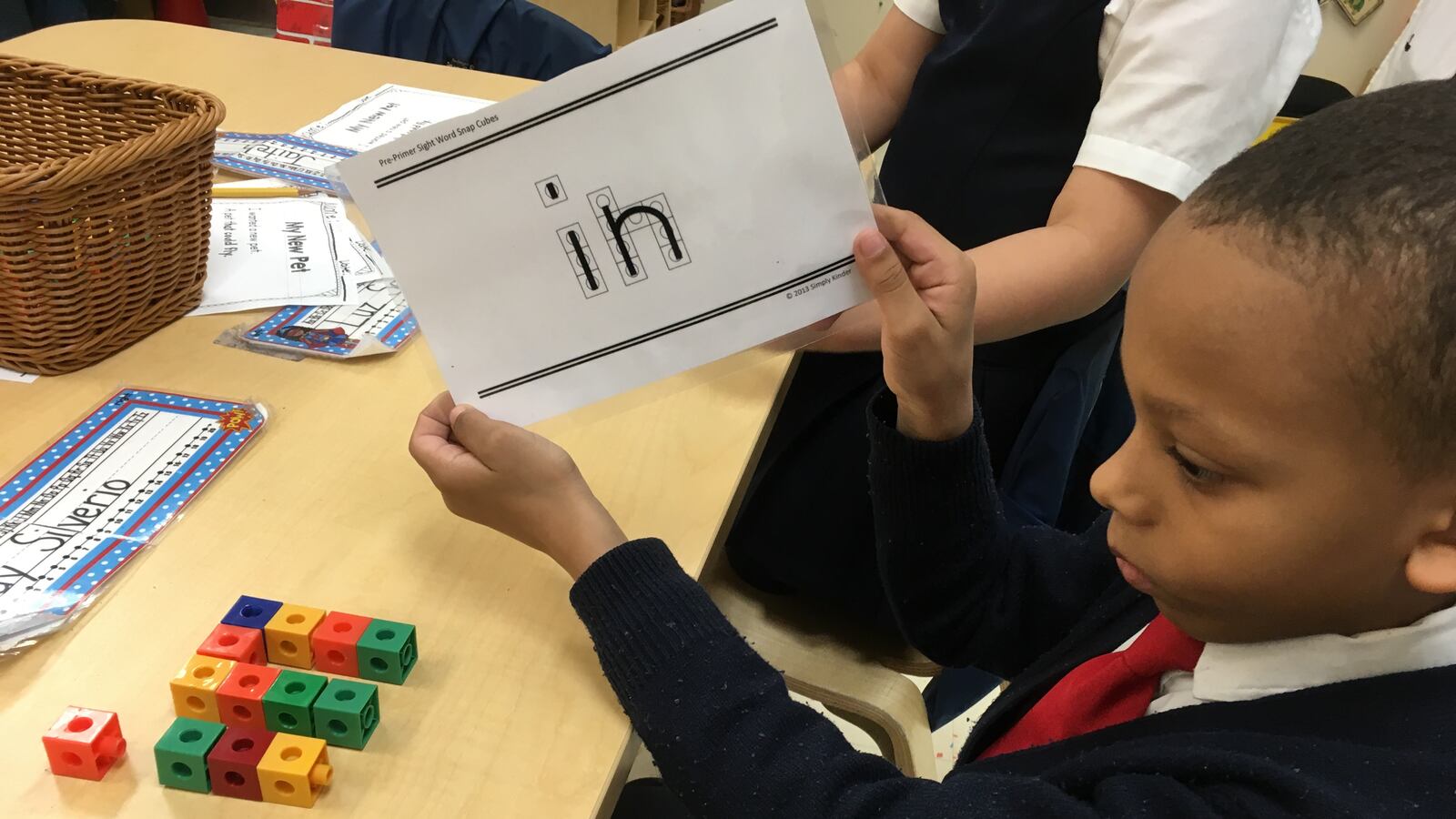

Back in Taveras’ classroom, Foster, the reading coach, checked in with the teacher. “Your timing: It’s getting much better,” Foster said quietly. Taveras nodded, her eyes scanning the room. Her students were split into small groups, each working at prepared stations where they reinforced their reading skills by playing with objects like play dough to shape out letters, multicolored Unifix cubes to form short words, and a word-based memory game on the rug. “We talked about shortening your lesson to 15 minutes and you nailed it,” said Foster.

Taveras headed to her desk where five children were waiting to do small group work. “Pull out your flashcards with the words ‘IS’ and ‘MY’,” she instructed the group. Foster pulled up a chair to observe. The extra attention helps children deepen their grasp of specific letters and sounds.

As one of ERM’s 10 coaches, Foster works in five schools, each at a different stage in its three-year relationship with the program. After an intensive multi-day training session for teachers and principals at ERM’s headquarters, schools receive 30 days of coaching over the first two years. That number decreases to 15 days in the third year. (P.S. 218 purchased another 15 days this year to provide reading instruction training for new hires and to continue strengthening the skills of existing teachers.)

Foster works individually with teachers to develop targeted teaching strategies, help create reading lessons, and train teachers and administrators to assess and monitor growth, of both students and teachers. She often starts with a school’s lead teachers — frequently modeling teaching skills and techniques in the classroom — who then share lessons learned with other teachers in the grade.

“Probably the hardest part of my job is changing mindset, because the kids can do a lot, but sometimes teachers and administrators aren’t aware of how much kids — even struggling students — can accomplish,” said Foster. “So part of my work is encouraging teachers to say, OK, I’m going to read this text, even though it’s hard, and the kids can grapple with it.”

Because reading proficiency has such a huge impact on later learning, the challenging task of teaching young children to read must be “job one for elementary teachers,” according to a 2016 report by the National Council on Teacher Quality. Yet just 39 percent of the nation’s 820 teacher-prep programs cover the essential components of effective early reading instruction.

“Poor teacher prep for reading has been going on a long time,” said Cáceres, the principal at P.S. 218. “Yet I haven’t met a teacher who can’t master it. But the schools that perform well, they all have high-level coaches. After that, success depends on two things: the quality of the coaching and how open a teacher is to receiving professional input.”