Growing up as a student of color in New York, Abigail Salas Maguire says she struggled to connect with the material she read.

“When I was in school and I was reading ‘Little House On The Prairie,’ that was hard to relate to–meadows, and rolling hills, what is that? I don’t know what that is,” said Maguire.

Now as a fourth grade teacher at the Emily Dickinson Elementary School in Manhattan, Maguire acknowledges that finding relatable, authentic literature can be a “struggle,” even for her. She wants not only books in Spanish for her dual language students but ones that represent them as well.

Last week, Maguire and more than 400 other educators came together at the Reimagining Education summer institute at Teachers College of Columbia University to learn how to provide students with academic experiences that reflect the diversity of their schools.

Amy Stuart-Wells founded the institute three years ago primarily to provide white educators with hands-on strategies for creating culturally relevant subject matter for their diverse student bodies. She noticed a disconnect between policymakers and educators that she said was preventing the education system from adapting to the shifts in its student population.

In New York City, as in districts across the U.S., there is a gap between the race or ethnicity of teachers and many of their students. Eighty-three percent of students in New York City are Asian, black or Latino, while only 39 percent of teachers are, according to 2015-16 state data compiled by Education Trust-New York, an advocacy group that works to improve outcomes for students of color. (Education Trust and Chalkbeat both receive funding from the Gates Foundation.)

Some recent studies have linked teachers of color to better outcomes for students of color. They indicate that having a black teacher leads to black students having better test scores and fewer suspensions and expulsions.

The city has some programs in place to bridge this divide. Earlier this year, the city pledged to spend $23 million on anti-bias training for its public school teachers. This includes $4.8 million for training for implicit bias and culturally responsive practices in 2019. The funding was largely a response to a push by activists, fueled by allegations of the mistreatment of students of color in some classrooms and discriminatory practices by some administrators.

But Stuart-Wells notes that the institute focuses more on teaching white educators, who make up the majority of the teaching force, how to create culturally relevant lesson plans and materials.

“This is a very grassroots kind of change. It’s not going to come through Washington, D.C. It has to come from the educator staff, from the people who have the expertise, in order for the program to be able to be effective,” said Stuart-Wells.

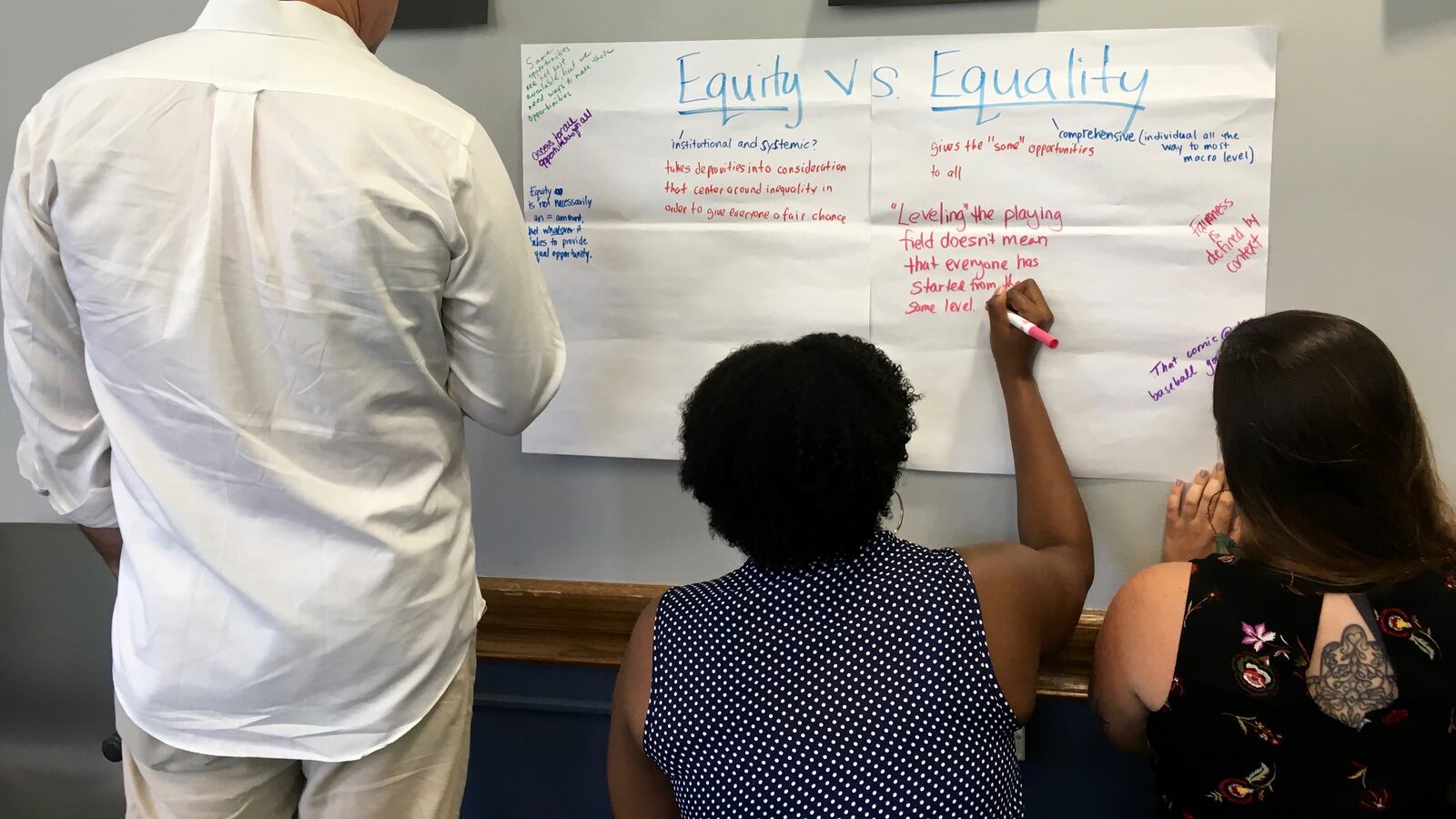

Over the course of four days last week, educators from 24 states and other countries heard from experts whose work was focused on equity pedagogy and had made strides in creating comfortable and inclusive environments for their students. After the presentations, participants broke off into workshops–or “pool parties,” as they were called–to debrief and share some of the ways they would apply what they were learning to their own communities.

Many of the people who lead the presentations and workshops are people of color, notes Detra Price-Dennis, an assistant professor of Elementary and Inclusive Education at the Teachers College of Columbia who has been a part of the institute since its creation.

“We had faculty of color, who are former teachers and who have gone through professional development leading, and other people of color lead the workshops and give keynotes,” said Price-Dennis. “Part of it is also understanding that as a white educator you don’t have to be a person of color to appreciate the genius of the students in front of you- just appreciate.”

The institute touched upon the importance of providing students of color with spaces to learn specifically about their culture and shared some examples of this in practice. This year at the Harry S. Truman High School in the Bronx, students with families from African countries like Ethiopia, South Africa, and the Ivory Coast came together every Thursday afternoon to learn about their nation’s history and politics. Known as the “Africa Club,” the group was created by assistant principal Jordana Bell, who saw an opportunity to make students feel more comfortable and connected to their community.

“Before the Africa club, there was no connection between teachers and students– it was just get your work, get out,” said Abel Zewde, a student at Harry S. Truman who spoke with a group of his peers about his experience in the Africa club. But in our differences we found unity. We learned what it truly means to be in a social group that you’re appreciated in.”

For recent Truman graduate Mannixs Paul Jr., being able to learn about his country at school meant finally being proud of his heritage.

“I never liked to wear native clothes from Nigeria,” said Paul. “But last week I looked at [Nigerian clothes] and I almost cried because I was like, it’s what I am missing! For a long time I’ve been trying to push away the culture. Now, I’m trying to make it a big part of my life.”

Training is just the starting point and may not be enough on its own, said Nicholas Donohue, president of the Nellie Mae Education Foundation, who attended the institute. Ensuring that students are given equal access and culturally relevant material not only means changing what is taught and how it’s taught, but also changing who is leading education reform and who holds positions of power.

“If you really want to change the system, the practices matter, but they will pale and fail if we don’t address structures,” said Donohue. “Reorganization isn’t enough, it’s about the policy and rules of engagement that drive the effort.”

For Stuart-Wells, being able to connect educators under a shared cause is what makes the institute meaningful.

“We are uniting people who are struggling with these issues, so we are creating and tapping into a movement to reclaim this field and honor the diversity of cultures that are around us, and bring them into the curriculum,” she said. “You come, we learn a lot and we stay connected.”