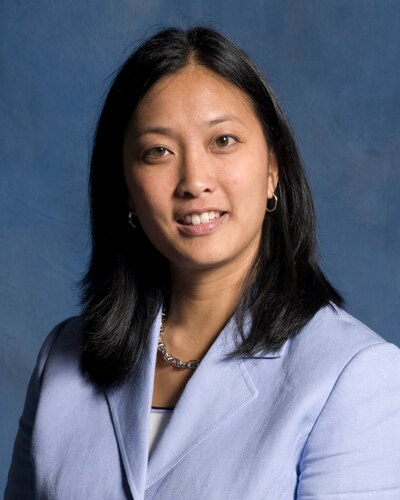

Two very different teaching experiences inside the same Manhattan school shaped Linda Chen’s career.

When she joined P.S. 163 as a teacher in the city’s sought-after gifted and talented program, Chen found training opportunities that challenged her to improve her craft and the materials she needed to engage her students.

Things changed after she transferred to a general education classroom in the same Upper West Side school, only to find much larger class sizes and fewer resources.

“I saw equity challenges under one roof that I knew needed to change,” Chen said in an interview with Chalkbeat. “I knew I wanted to do something about that.”

After rising to become a principal here, Chen spent the next decade crisscrossing the country, filling top education roles in urban districts including Baltimore and Boston. When school starts Wednesday, Chen will return to New York City to serve as the new chief academic officer.

In Chen, schools Chancellor Richard Carranza has likely found an ally in his push for more diverse schools. Her approach may feel familiar in other ways, too. Colleagues say Chen cares deeply about helping teachers become better at their jobs — something former Chancellor Carmen Fariña put at the center of school improvement.

Carranza created the chief academic officer position shortly into his five-month tenure here, saying the massive bureaucracy he inherited has struggled to collaborate in ways that make sense inside schools. The role brings together overlapping departments that touch the classroom in vital ways under the same leadership.

“I had great, hard-working people,” he told Chalkbeat in a recent interview. “But rarely did they work across each other’s silo.”

The last time New York City had a chief academic officer, it was forced to. In 2010, the city struck a deal with state officials: In exchange for approving Cathie Black, a schools chancellor who had no experience in education, former Mayor Michael Bloomberg agreed to appoint a chief academic officer as second in command. Black stepped down after 95 days.

When Mayor Bill de Blasio was elected, he tapped Carmen Fariña to lead the city’s schools. With more than 50 years of experience in the system, Fariña did away with the position. Before she retired this winter, Fariña served as chief executive and top educator, with a cabinet of 22 people reporting to her.

When Carranza came on board this spring, he found an “unwieldy” leadership structure. In schools, that could play out in frustrating ways. Principals and teachers complained about fuzzy lines of responsibility and support systems that were far removed from what teachers really needed.

Mike Magee, the head of Chiefs for Change — an education advocacy group — said that it’s increasingly common for school leaders to rely on a chief academic officer to steer the important work that happens in classrooms. Having someone dedicated to curriculum development and training frees up the chancellor to focus on systems issues, he said — something Fariña was often criticized for neglecting.

“The chief role in a school district, the superintendent role, is a role where you have a wide variety of responsibilities,” he said. “To have a leader on your team who can have a laser-like focus on not just the academic side of the work but on curriculum,” is a smart move.

Starting in 1997, Chen taught in New York City for about three years before joining the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, founded by the influential Columbia professor Lucy Calkins. Chen went on to become principal of P.S. 165 in Manhattan, a dual language school that she said also served a sizable number of students with special needs.

While there, some parents protested Chen’s decision to discipline a well-liked assistant principal. But Calkins said Chen was better known for encouraging active lessons with plenty of opportunities for students to talk and for spending time in classrooms “helping teachers study their kids.”

Chen left New York for Philadelphia in 2008, where she rose to become an assistant superintendent. From there she headed to Boston, where she made sure teacher evaluations and curriculum were aligned with new learning standards, and then to Baltimore, where she was chief academic officer.

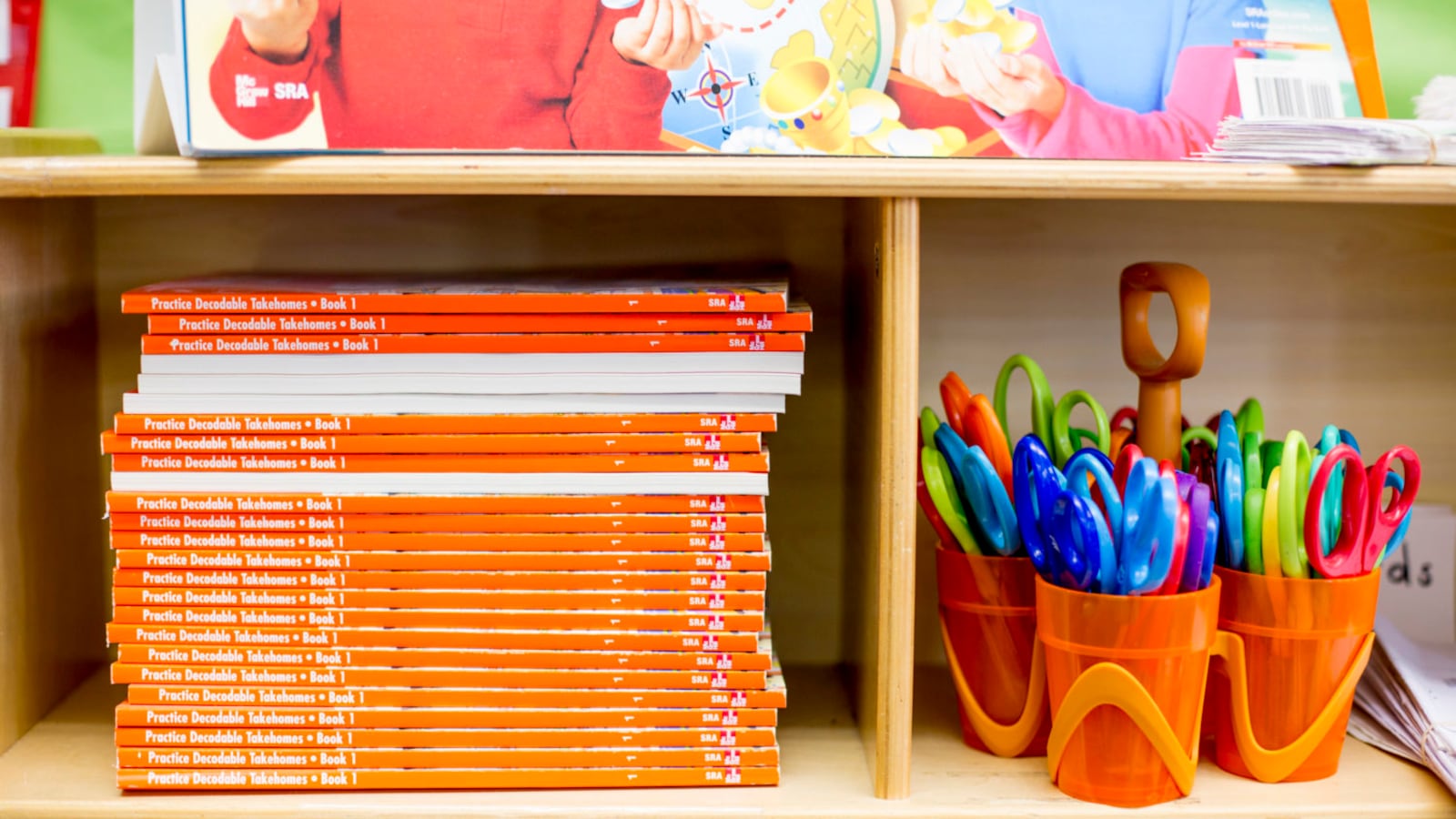

The former head of schools there, Greg Thornton, said Chen ushered in new, formative assessments to give teachers more information about what their students really knew, and she was focused on boosting student engagement through the materials that were used in the classroom.

“Student engagement was her really big thing,” Thornton said. “We had kids who were disengaged, and you can’t win that way.”

Chen also helped champion a new way of supporting principals in struggling schools, though some complained it curbed the freedom of school leaders to make decisions. She served only two or three years in each of her roles, though that’s not unusual in the often politically fraught world of education.

Chen thinks things will work out differently in New York City.

“In this case is you have a mayor who has a clear agenda… You have a chancellor coming in the middle of this who is completely aligned,” she said. “So you can move forward.”

In her portfolio as chief academic officer: the Division of Teaching and Learning, which coordinates teacher training and is responsible for curriculum; the department that oversees special education; and the department that serves students who are learning English as a new language.

It will be up to Chen to make sure all those offices work together to support students and teachers. That may mean that experts in teaching students with disabilities or limited English skills work side-by-side with curriculum gurus to create classroom materials that cater to students’ different needs, but also challenge them. The departments she oversees then might work together to coordinate training, making sure teachers know how to use the new materials well.

“There has been collaboration, but it has been somewhat informal and not structured in a way with the full intent for access,” she said. “I would love for [teachers] to be able to see that there is something in the resources we provide for every one of their students.”

For Chen, that means recognizing the “cultural needs” of students. Integration advocates have pushed the city to focus more on culturally relevant education practices, calling for classroom materials that include representations of different students and also reflect a diversity of viewpoints. In a system that is 70 percent black and Hispanic students, advocates say this is key to engaging students and even boosting academic achievement.

Chen said she looks at the work of culturally relevant education in two ways: Providing classroom materials that are inclusive of all students, and working with adults to recognize inequities in the school system.

“We can create materials and put them in teachers’ hands, but if we don’t attend to their needs and their development in this mindset, then they won’t thrive,” Chen said.

Former colleagues say diversity is an issue that Chen championed in her previous roles. Maria Pitre-Martin, who worked with Chen at the Philadelphia public school district, said it was front-and-center whenever making decisions about classroom materials.

“That was always part of the criteria, and it was pretty much a nonnegotiable, making sure that we had culturally relevant material in front of our students,” ” said Pitre-Martin, who is now a deputy state superintendent for North Carolina.

Chen will also have to coordinate the way the city trains and supports its educators, something the department has sometimes struggled to get right. Teachers in New York City have said the training they’re offered often cuts into their time in the classroom and feels disconnected from their needs.

It’s a notorious issue across the education field. In Jerry Jordan’s more than 30 years as an educator, the head of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers said he has suffered through plenty of useless training sessions. But he said Chen was known for bucking that trend, and delivering relevant professional development in her time in the Philadelphia public school district.

“People learned from it,” Jordan said. “There are times when you attend a professional development session and you say, ‘I just wasted two hours.’”