New York City’s proposed contract with its teachers union covers the entire city, but all officials seemed to want to talk about Thursday was the Bronx.

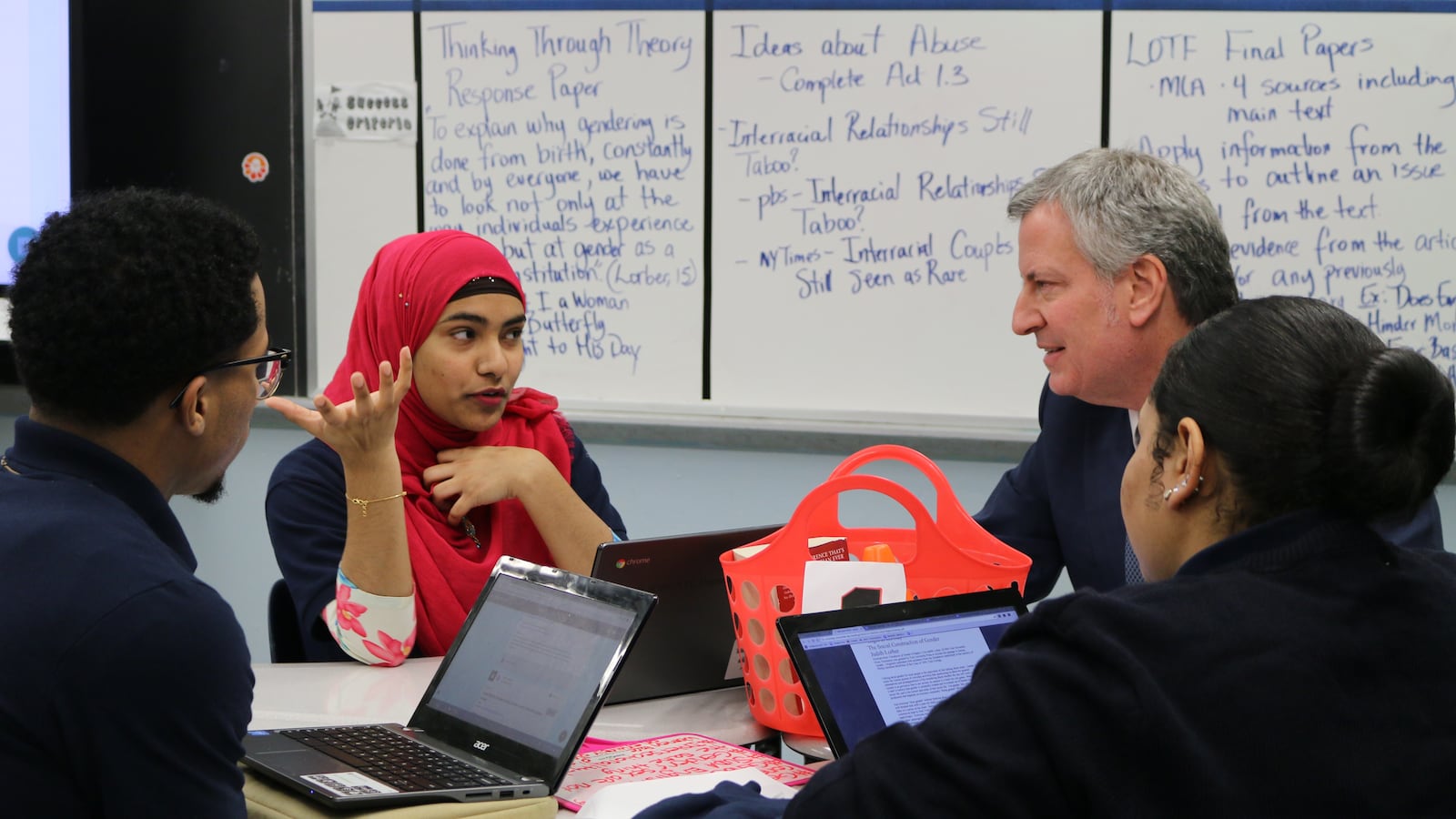

“We know there is so much more that can be done for the children of the Bronx and of the schools of the Bronx,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said Thursday at a press conference announcing the contract deal.

“Schools in the Bronx had been historically underserved,” said Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza.

The new contract creates what officials are calling “The Bronx Plan,” through which 180 schools will be able to pay an extra $5,000 to $8,000 to educators who take hard-to-fill positions. Two-thirds of the schools will also give educators a formal role in decision making. Both elements echo ideas that the city has tried out before but fell short of expectations.

Schools that qualify for the pay incentive will be identified this fall, and, contrary to the plan’s name, could include some in other boroughs. Officials said the plan was named for the Bronx’s challenges, which include low student performance and persistently high teacher turnover. The borough’s six districts all have turnover rates in the top third in the city, according to the union.

The plan represents an unusual focus on a single borough in citywide bargaining — and a repudiation of the city’s previous, top-down efforts to improve long-struggling schools.

“We’re going to move education by listening not just to teachers, but to parents and school communities about what they need,” said United Federation of Teachers chief Michael Mulgrew.

A contract that focuses particular attention in one area over others is “very unique,” said Maria Doulis, vice president of the Citizens Budget Committee, a nonpartisan watchdog of city and state finances. But, she said: “It’s also probably appropriate and long overdue.”

“Usually in labor contracts what prevails is a standard of uniformity,” she said. “But I think, especially in a city that spends as much on education as New York, you want to be targeting resources to the schools that need them ”

With the pay incentives, the city hopes to attract highly qualified educators — and keep them — where they’re needed most.

“The key to great schools is great teachers,” de Blasio said. “You have to make sure they are where the need is greatest. This is what allows us to do that.”

Bronx parent activists, including those in the New Settlement Parent Action Committee, have clamored for the city to address the borough’s staffing challenges.

“I had an experience with my son where he had a new teacher every week in math. That doesn’t help students,” said Esperanza Vazquez, the mother of a 12th-grader who is a member of the action committee. “They have to be teachers who are highly qualified, with experience, to teach our children.”

The city does not plan to tie the incentive pay to teachers’ effectiveness at boosting students’ test scores. Mulgrew emphasized on Thursday that the new program is “not merit pay” — a third rail for unions. (A merit pay program in place between 2007 and 2010 offered bonuses for teachers who boosted their students’ scores, but teachers routinely chose to distribute the money across their whole schools, and the city abandoned the initiative after a study found “no impact on student achievement.”)

It’s unclear how much the borough’s staffing challenges have to do with teacher pay. Student poverty presents many hurdles for local schools that can make teaching in them taxing, and some neighborhoods are poorly served by public transportation, making them hard to reach for teachers who live elsewhere. The incentive amount “is about what it would take to get me to go back to the Bronx,” one teacher wrote on Twitter.

Referencing a pot of federal funding that is dedicated to schools with many needy students, the teacher added: “I will be completely frank in saying my job is much less difficult now that I work in a (still Title I!) school in Manhattan.”

It’s also unclear how widely the city expects the new incentive option to be used. Under the the terms of the expiring contract, the city could offer higher pay to all teachers at a “hard-to-staff” school, but the option was used at only one school, according to the city education department.

One difference in the new rules: the higher pay can go to only some teachers at the schools, depending on what they teach.

Another difference, according to the city: the second prong of the Bronx Plan, which calls for 120 schools to become “Collaborative Schools” where educators and community members pursue homegrown solutions to local challenges.

Mulgrew said he’s “not as optimistic as others” that the extra pay alone will make a big difference. More important, he said, is school culture and leadership — which the Collaborative Schools plan is meant to address.

“To me, you get tied to a school because you love the kids and you love the culture of the building,” he said. “I think the other parts of the plan are what’s going be the determining factor of whether this is successful or not. It will not be based on the differential.”

In those schools, the city says teachers and community members will be given “a substantial voice” in decision-making, with a focus on using data to zero in on school needs. Committees of six to 12 members (half appointed by the principal and half picked by the school’s union chapter leader) will choose strategies to improve performance, staff retention, and school climate.

Each school will quality for an annual $25,000 “innovation fund,” and the committee will decide how to spend it.

“These schools will now have this ability to come up with their plan,” Mulgrew said. “A school community comes together and says, ‘All right, we understand the challenges we’re facing. We understand the children in our community. This is what we’d like to do.’”

Other city efforts to give struggling schools extra money or empower schools in order to improve them haven’t had the dramatic impact that was promised. Most notably, the current Renewal program gave low-performing schools far more money than the Bronx Plan would, along with academic support. But the initiative has not driven the dramatic gains the city promised.

And the city’s last contract with the union created a program known as PROSE that allowed teams of teachers and administrators to tweak the union contract at more than 100 schools, creating flexibility around scheduling and other provisions. The union described the program remarkably similar language as Collaborative Schools, saying PROSE would “empower” teachers and acknowledge that “the solutions for schools are to be found within school communities.” De Blasio called it “reform on a grand scale,” but the changes pursued were modest and an analysis by a group critical of the mayor’s efforts found no test score payoff.

Mulgrew acknowledged that Collaborative Schools are meant to replicate aspects of PROSE and defended the program as effective.

“I walk into a PROSE school and say, ‘Is this a school where I want to teach?’ he said. “These are schools, by and large, that I would want to teach in and people are happy in.”

It’s unclear why collaboration with people outside of the school would need to be baked into the city’s contract with the teachers union. Already, many schools in the Bronx and elsewhere work closely with families and community groups, involving them in programs and planning.

Union officials say the contract is the most effective tool they have to make change in the city, so it makes sense to use collective bargaining to tackles issues even beyond pay, benefits, and work conditions for teachers.

The Bronx plan is already being debated among the union members who will be asked to ratify the contract.

“The idea of the majority of resources being used in the Bronx is going to make me vote no,” one teacher, Christopher Theodore, wrote on the union’s Facebook page Thursday night. “Resources have to be distributed evenly. To think that the other boroughs don’t need the same assistance is short sighted and unfair to a lot of kids who need access to better resources.”

Another teacher, Allyson Robley, responded with an analogy from the classroom. “The Bronx as a borough has historically been underperforming so they need the most support,” she wrote. “While giving equal help sounds sounds good, it’s not fair. Do you give the same support to all of your students? No! The struggling students receive the most intensive instruction.”