This story is part of a partnership between Chalkbeat and the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica. Using federal data from Miseducation, an interactive database built by ProPublica, we are publishing a series of stories exploring inequities in education at the local level.

Eugene Harding knows what it’s like to feel stretched thin. A social worker with 25 years of experience in New York City’s public schools, he splits his time among three Manhattan high schools with a collective enrollment of more than 2,000 students.

“It’s Wednesday, and I have to go downtown, and it’s Thursday at another school, and I’m still thinking about the student from Monday,” he said.

Harding knows some crises won’t wait, such as when he’s told students are engaging in dangerous behavior like cutting themselves. But at the same moment, another student may show up to talk, and the problem could be minor or serious. “Like an emergency room, you try to triage,” he explained. But sometimes, he said, “You find out the person who really needed you, needed you last week.”

Harding is part of a legion of school counselors, social workers, and psychologists who help New York City students navigate everything from class schedules to family crises. Their role is essential, according to both research and the people they work with, yet advocates say the city has struggled to make sure enough of them are working in city schools.

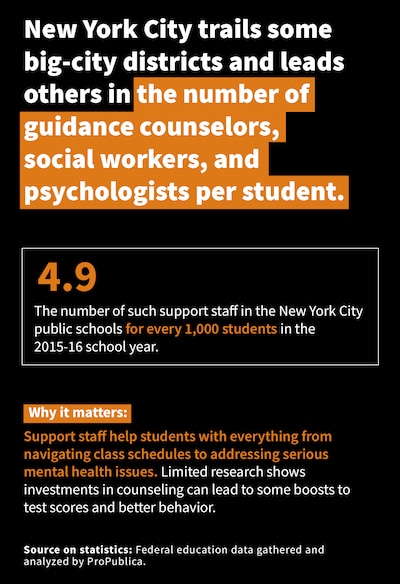

In the 2015-16 school year, New York City had 4.9 support workers for every 1,000 students, according to federal data — fewer than in many cities, including Los Angeles or Washington, D.C., though more than in some others, such as Chicago and Broward County, Florida. The data, compiled by ProPublica from federal civil rights reports from every school in the country, show how much ground the city must cover if Mayor Bill de Blasio is to achieve his goal of using schools to combat the effects of poverty.

Under de Blasio, the city has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into hiring additional guidance counselors, opening school-based clinics, and expanding access to mental health services for students. People who work in schools say they’re starting to see that money turn into additional help, but many say more still is needed — and they worry that the patchwork of providers being constructed could fall apart when a new mayor with new priorities takes office in the future.

And it’s unclear whether the new investments will be enough to help students in the city’s most troubled corners, at a time when some challenges that they face, especially homelessness, are on the rise. While national guidance counselors and social workers groups recommend having one counselor and one social worker each for every 250 students, in schools with “intensive” needs, that ratio falls to one social worker for every 50 students.

Across the city, that recommendation resonates with the counseling staff working to help students.

P.S. 398 in Crown Heights has a guidance counselor, social worker, and psychologist. Typically, guidance counselors and psychologists focus on students’ learning inside the classroom, while social workers engage in the emotionally wrenching work of helping them grapple with the challenges presented by their lives outside of school. At P.S. 398, where almost half of the 300 students are homeless, everyone pitches in to meet the needs of families and students. Still, Jemma Byam, the lone guidance counselor, said she wishes she had more one-on-one time with students.

“There’s not enough time. It’s always an ongoing, continuous situation we deal with,” she said.

At Curtis High School on Staten Island, school psychologist Kelly Margaret Batson says a backlog of more than 30 cases has piled up — each representing a student who is overdue for an evaluation into whether their special education plans are meeting their needs. While she’s grateful the school has a clinic that provides extra mental health support for students, her day is often interrupted by those with immediate needs, pushing her cases further past their deadlines.

“If we would have enough time, we could really work with the kids and try to avert crises before they happen,” Batson said.

Leanne Nunes, a junior who attends high school in the Bronx, cried in the bathroom when she was overcome with anxiety at the start of the school year. Her school has a brigade of guidance counselors, but the social worker whom Nunes previously relied on left, and the position hasn’t been filled this year. Nunes wiped her face and returned to class without anyone noticing she was upset.

“I was so angry that I didn’t have anybody,” she said, noting that she’s reluctant to share personal matters with an adult she has no connection to.

Significant investments

De Blasio’s election in 2013 promised change. His administration ushered in a radical shift in the way the city sought to improve education in the country’s largest school system. Rather than closing struggling schools, the city has spent almost $1 billion to infuse them with extra resources.

The administration also launched the largest community schools movement in the country, investing in services such as health clinics across more than 200 schools. Another $17 million annually has gone toward Single Shepherd, which provides more than 100 additional counselors and social workers for the neediest school districts. The most recent city budget dedicates $14 million to support homeless students with extra social workers. And through other programs like ThriveNYC, an initiative of First Lady Chirlane McCray, officials say that every school now has access to mental health services.

“We’re committed to meeting the needs of every student so they succeed academically, socially and emotionally,” education department spokeswoman Miranda Barbot wrote in an email. “We’ve made significant investments in initiatives to improve school culture and initiatives to increase the number and effectiveness of guidance counselors and social workers across the city.”

Principal Daniel Russo said the city’s efforts have made a real difference at his school, P.S. 294 in the Bronx. About 30 percent of students there — 150 in total — are in temporary housing, which means students sometimes have to travel long distances to get to school, and may show up to class hungry or sleepy. P.S. 294 has help through Bridging the Gap, a city program that has put 69 social workers in schools with high rates of student homelessness. Thanks to the city’s community schools push, a nonprofit provides mental health services to families.

When the school social worker recently noticed in counseling sessions that one student could benefit from mental health services at home, the nonprofit was able to step in with family counseling.

“For us, it was important to take a real, holistic approach to how we support families,” Russo said. “Everybody’s needs are going to be met.”

‘We’re lacking’

Staffing data that the City Council started collecting in 2015 bears out Russo’s experience — but also suggests that many other schools aren’t so lucky. Last year, the city reported there were 2,880 guidance counselors serving the city’s 1 million students, or one counselor for every 348 students. That ratio has come down by about 7.5 percent, or 28 students, over the last four years.

But there were only half as many social workers employed by the city, suggesting that each one is working with an average of more than 700 students.

“The data is very clear on how much support staff we’re lacking,” said Mark Treyger, chairman of the City Council’s education committee. He advocates that the city meet the national recommendations for guidance counselors and social workers, but could not immediately say how much that would cost. “I don’t think you make an effective dent if you don’t close that ratio.”

Harding, the social worker responsible for 2,000 students at three city high schools, described some of what students are up against. “Somebody in their family was recently arrested, or an ICE raid results in an uncle being taken away, and they come to school and ask a teacher or a social worker,” he said, because they know who to reach out to for help. “That family, due to poverty, doesn’t know who to go to, how to find a lawyer.”

Harding, who works at the Richard R. Green High School of Teaching, Urban Assembly School of Business for Young Women, and The High School of Fashion Industries, tries to maximize the difference he can make by conducting group counseling sessions.

During students’ lunch periods at one campus, for example, he conducts a regular group session called “Hot Topics with Hot Pockets,” where students can hang out and raise issues of concern. The conversation, which Harding sees partly as an exercise to build bonds he can rely on when crises later arise, runs the gamut, from suicidal feelings to current events to “tampons versus pads, which are better?”

At some of the schools he works in, Harding says guidance counselors “definitely try to help out,” but they can feel torn in as many directions as he sometimes does. Since guidance counselors often focus on keeping students on track academically — troubleshooting obstacles that can keep students from graduating on time, for instance — they don’t always “have the time to sit down one-on-one and talk with a student who’s going through a crisis,” he said. School psychologists, meanwhile, can be similarly pulled away by mandated evaluations of students with disabilities to see what services they need. The number of social workers, by contrast, remains critically low in many schools, the city’s statistics show.

‘It changes outcomes’

Research suggests schools have an incentive to beef up their support staffing. One commonly cited study from 2014 linked higher test scores and better discipline to more counselors. The study looked at one Florida district from the 1995-1996 through the 2002-2003 school year, when graduate students who were counseling interns bulked up staffs that had one full-time school counselor.

Specifically, boys’ test scores and behavior improved, according to the study. Girls’ behavior improved, too, but their test scores didn’t significantly budge.

“What we find is that increasing the number of counselors or lowering the student-to-counselor ratio affects student discipline, and subsequently improves student achievement and test scores,” said Scott Carrell, an economics professor at the University of California at Davis who co-authored the study and several related ones.

In New York City, the benefits of adequate counseling can be readily seen at Bronx Arena, an alternative high school in the Bronx that has a small army of counselors and social workers to help students who have struggled at traditional high schools, and are often at risk of dropping out. The school’s principal, Ty Cesene, said the school has a ratio of one counselor for every 27 students.

This support team can focus on out-of-school issues that often affect how well students do in school, said Anne Zincke, a program director at SCO Family of Services, which helps fund the counselors at Bronx Arena, where Zincke also works. Counselors there may show up in court alongside students accused of everything from turnstile jumping to felony charges. The small ratios also allow counselors to forge relationships that help students feel safe and comfortable enough to disclose when they need help paying for groceries, for example.

With those kinds of needs addressed, teachers can focus on teaching — and expectations can remain high for students, she added.

“When you get to that level of support, it changes outcomes,” Zincke said. “It’s very hard to say, ‘My mother left, and I don’t have any food in the refrigerator.’ They won’t do it. It’s not in the nature of a teenager.”

‘It’s too much for the counselors’

And yet city students are in fact asking for help. When students across the country recently marched out of their classrooms in the wake of a deadly school shooting in Florida, high schoolers in the Bronx didn’t call for more gun control. Rather, they shouted: “We need more social workers and counselors in all schools!”

Parents and elected officials also say counseling gaps need to be plugged.

Shortly after a fatal school stabbing — the first in the city in decades — a group of parent advocates found that there is only one social worker for every 589 students in the South Bronx, nearly 12 times the level recommended for needy communities.

A report by the Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer said the city’s push to provide more mental health supports is “patchwork” and “falling short,” with heavy caseloads for consultants who are supposed to connect schools with services. Yet some schools, Brewer said, were totally unaware that help is available to them.

More recently, Treyger, the city councilman, has demanded that the city education department hire more permanent support staff. While Treyger often points to individual Renewal or community schools that have made strides with help from social workers, he says the programs are too dependent on insecure nonprofit partnerships.

“I’m talking about full-time DOE employees, and not relying on an inconsistent funding stream,” Treyger said. “This mayor supports the community schools approach. The next mayor may not.”

On a full day of lunchtime counseling, Harding, the social worker, might see 40 to 50 students who swing by in groups of about 10 for each session. Still, he can’t help worrying about the many hundreds of students who may not join his lunch group or seek out help even if there are problems below the surface.

“I do think about what about all the ones who I never see,” he said, “and I just don’t know who they are.”