New York City is poised to end its $750 million Renewal Schools program, which city officials knew within a year of its launch in 2014 was unlikely to produce the promised “fast and intense” improvements in academic achievement in many of the city’s lowest performing schools, the New York Times reported on Friday.

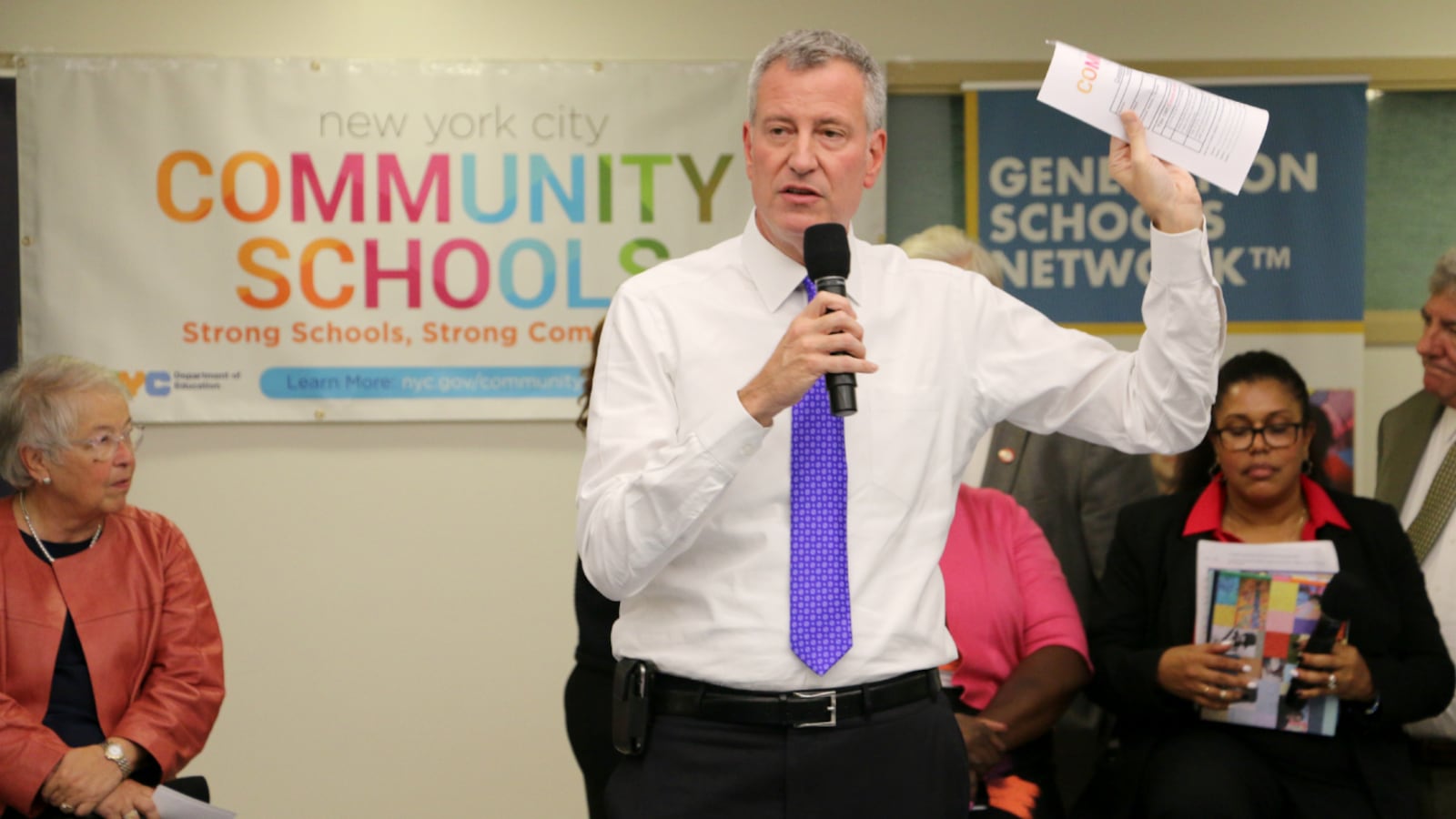

The education department would not confirm the program is winding down and did not respond to repeated requests for comment. But in his weekly appearance on WNYC’s Brian Lehrer show, de Blasio did not deny the program is ending, and even suggested it is reaching its “natural conclusion.”

However, he bristled at the characterization that the program — which was meant to improve long-struggling schools by giving them extra social services and academic support, including on-site health clinics, coaches for teachers and extended school days — was deeply flawed.

“I think it was the right idea to say we have to invest in these schools,” de Blasio said.

This left educators, parents and students guessing on Friday about what’s next for the 50 schools that are still a part of Renewal, which has been one of the mayor’s signature education initiatives.

“What am I supposed to do now as a parent for my child’s school that’s on the Renewal list?” a parent whose child is in the 11th grade at Martin Van Buren High School asked de Blasio on the show.

One education department administrator, who works with multiple Renewal schools and spoke on condition of anonymity, said it is not yet clear, if the program ends, what the city’s exit strategy would be and whether the schools will continue receiving additional supports and resources.

“It may mean an end to the extended day, it may mean an end for the coaching help, it may mean an end to the community schools partners” the administrator said, referring to nonprofit organizations that have been paired with every Renewal school and which provide services ranging from extra social workers to afterschool programs.

“There seems to be good reason to think that the program is going to be shut down after three quarters of a billion dollars has been pumped into it without much positive impact to point to,” said Aaron Pallas, a researcher at Teachers College who has studied the Renewal initiative.

Two independent analyses conducted by outside researchers, including the one by Pallas, have found the program has had a limited impact on academic performance. (The Times also cited results from an unpublished study from the RAND Corporation, which said on Friday that it does not comment on research in progress and expects to release its full evaluation of the city’s community schools program next year.)

Whether de Blasio will face pressure to come up with a new strategy for intervening in the city’s lowest-performing schools — and what that might be — is unclear. Research does not point to any single approach for turning around low-performing schools. Mayor Bloomberg’s efforts to shut down such schools and replace them led to some gains, research has found, but school closures can also backfire if they only serve to disrupt a student’s education and don’t wind up at a better school.

“In fairness,” Pallas noted, there are not obvious or easy models for the kind of rapid turnaround that de Blasio promised. “The alternative is perhaps quickly closing schools and quickly shunting students in Renewal schools to other schools,” he said, “but we know that’s not great for all students, and it takes time to do it responsibly.”

City officials have insisted that many Renewal schools have made strides, though they have also closed or merged schools that haven’t measured up. Of the 94 original schools, 14 have been closed, nine have left the program after being merged with other schools, and city officials said 21 have shown enough progress to slowly ease out of the program.

But within a year of its beginning, the Times reported, city officials privately worried that roughly one third of Renewal schools were likely to see little or no improvement — yet continued to champion the program and kept most of the schools open.

Even outside supporters of Renewal were concerned that de Blasio had set unrealistic expectations for an intervention that, at best, was likely to be slow, arduous work. In his speech announcing the program, the mayor promised the schools would see rapid improvements within three years, and the city would “move heaven and earth” to ensure this success.

Moreover, if the Renewal program faltered on a national stage, this failure could undermine the broader “community schools” movement, which has shown signs of promise and holds that struggling schools need extra social services to overcome the effects of poverty that can impede student learning — a central tenet of de Blasio’s turnaround strategy.

De Blasio hoped Renewal would be a definitive answer to former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s approach of closing dozens of schools and opening new ones, a process that often drew outrage from school communities and prompted lawsuits from the city teachers union.

“Closing them and replacing them with something that couldn’t necessarily address the problem any better was not the solution,” de Blasio said Friday.

Signs of strain and missteps, however, were evident from nearly the beginning. Expecting quick and significant gains from schools that had struggled for years put enormous pressure on them, many of which did not immediately receive clear guidance — or promised support — from the education department.

Though Renewal schools had seen declining enrollment well before the program started, the schools struggled to attract students. Education officials, who had initially refused to release any benchmarks at all, eventually acknowledged the schools would get three years to hit targets other schools were expected to meet in one. (More recently, schools were even allowed to backslide and still meet their goals.)

Still, as the program gained steam, some school leaders said the extra support made a big difference. At Juan Morel Campos, a 6-12 school in Brooklyn, school officials used the extra coaches to help teachers adapt to a more rigorous curriculum. And at Longwood Prep, a high school in the Bronx, school leaders have implemented a new data system for identifying students who don’t show up to school.

But indications that the city might be readying to end the program have been accumulating for months. Though officials had previously toyed with the idea of adding schools to Renewal, the education department has acted as if it could be phased out.

Soon after being named chancellor, Richard Carranza criticized the program, saying it seemed to lack a clear “theory of action”; the initiative has gone without a permanent leader since its executive superintendent stepped down in March; and the city has not given Renewal schools goals they are expected to meet this year, despite doing so in the past.

De Blasio, however, sounded a defiant note on the Lehrer show on Friday. “I disagree with the premise of this [Times] article that this was in some way an idea that was not appropriate to the problem,” he said.