After years of declines, the number of suspensions handed out to New York City public school students increased last school year — the first jump since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014.

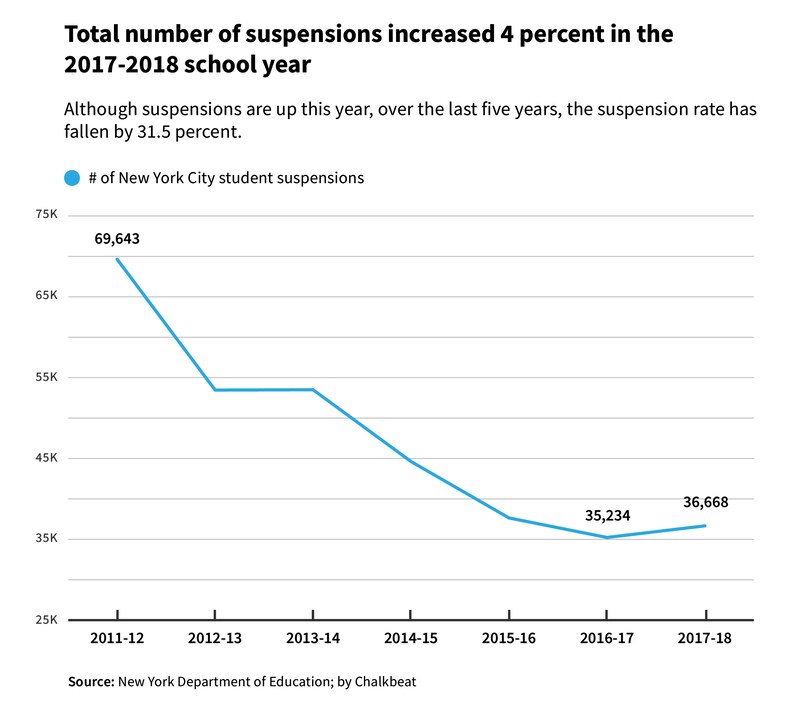

The total number of suspensions increased 4 percent in the 2017-2018 school year to 36,668, according to new data released Wednesday by the education department. Principal suspensions, which are handed out for less serious offenses, increased by 3.4 percent. Meanwhile, more serious superintendent suspensions jumped by nearly 6 percent.

The increase comes after a sudden 21 percent spike in suspensions during the first half of the school year but the rate declined in the second half of the year for an overall increase of just 4 percent.

[Related: Here’s what the numbers show for every school in New York City]

“We took swift action to implement and expand interventions,” education officials said in a statement but did not comment further about why suspensions increased so significantly in the first half of the school year, only to fall back in the second half, leading to the marginal increase overall.

As in previous years, black students and students with disabilities continue to be disproportionately suspended, while white students are underrepresented, a gap that slightly narrowed last school year.

New York City has joined many other districts working to reduce suspensions, especially for this population of students. But even supporters of the mayor’s efforts say the city still needs to do more to ensure schools aren’t funneling some student populations into the criminal justice system.

During a rally Tuesday afternoon on the steps of City Hall, activists pointed to a recent report from the city’s Independent Budget Office that found black students are more likely to receive harsher suspensions than students from other racial groups for the top eight out of ten categories of infractions. Rally participants also argued the city needs to step up efforts to replace school safety agents with guidance counselors and other mental health supports.

De Blasio has championed policies that make issuing suspensions more difficult — including among students in grades K-2 — and the education department has started requiring central signoff for suspensions for certain infractions. The city has also invested in training staff members to provide alternatives to suspensions, something that community advocates have asked for.

Although suspensions are up this year, over the last five years, the suspension rate has fallen by 31.5 percent. City officials added that major crimes in schools have decreased 29 percent since de Blasio took office. And in Brooklyn’s District 18, the education department has piloted a program that favors peer-mediation and other less punitive responses to misbehavior, a program that coincided with an 11 percent decrease in suspensions last year and which expanded to three other districts this year.

Yet the city’s new discipline policies have drawn criticism from some quarters. Some union officials and educators have complained that limiting schools’ ability to suspend students without proper training in alternative approaches has made schools more chaotic and dangerous, an assertion that is at least partially backed up by student and teacher surveys.

The data released Wednesday continues to show deep disparities, and many students of color note they continue to be disproportionately targeted for discipline. Research has shown that suspensions can have a long-lasting impact. They are associated with declines in students’ academic performance, and suspended students are more likely to drop out of school and enter the juvenile-justice system.

Malachi Davidson, a recent public school graduate who helps organize students to fight against harsh discipline practices, recalled being suspended in elementary school for a minor fight with one of his classmates. “It was scary. I was really struck to my core,” he said of the experience, which resulted in a weeklong in-school suspension.

About 46 percent of the city’s suspensions went to black students, even though they represent 26 percent of the student population. That’s slightly better than the previous school year, when that group represented 47 percent of the city’s suspensions.

White students accounted for eight percent of the city’s suspensions — essentially unchanged compared with the previous year — despite being roughly 15 percent of the city’s students. Hispanic students accounted for 39 percent of suspensions and are just under 41 percent of students.

About 40 percent of suspensions were issued to students with disabilities last year, up from 39 percent during the previous year. Overall, 20 percent of the city’s students have a disability.

There is research that some — though not all — of the disparities in school discipline are the result of bias from teachers and administrators. A study in Louisiana found that black students receive slightly harsher punishments than white students do while looking at the same altercation; other research has shown that black students are more likely to be suspended for discretionary offenses such as insubordination.

Black teachers are also less likely to suspend black students than white teachers. (In New York City, although 83 percent of students are Asian, black or Hispanic, less than 40 percent of their teachers are, according to data from the 2015-16 school year.)

“We have made significant progress,” said Deputy Chancellor LaShawn Robinson, who oversees school climate and wellness for the education department, “and acknowledge there is much work to do.”