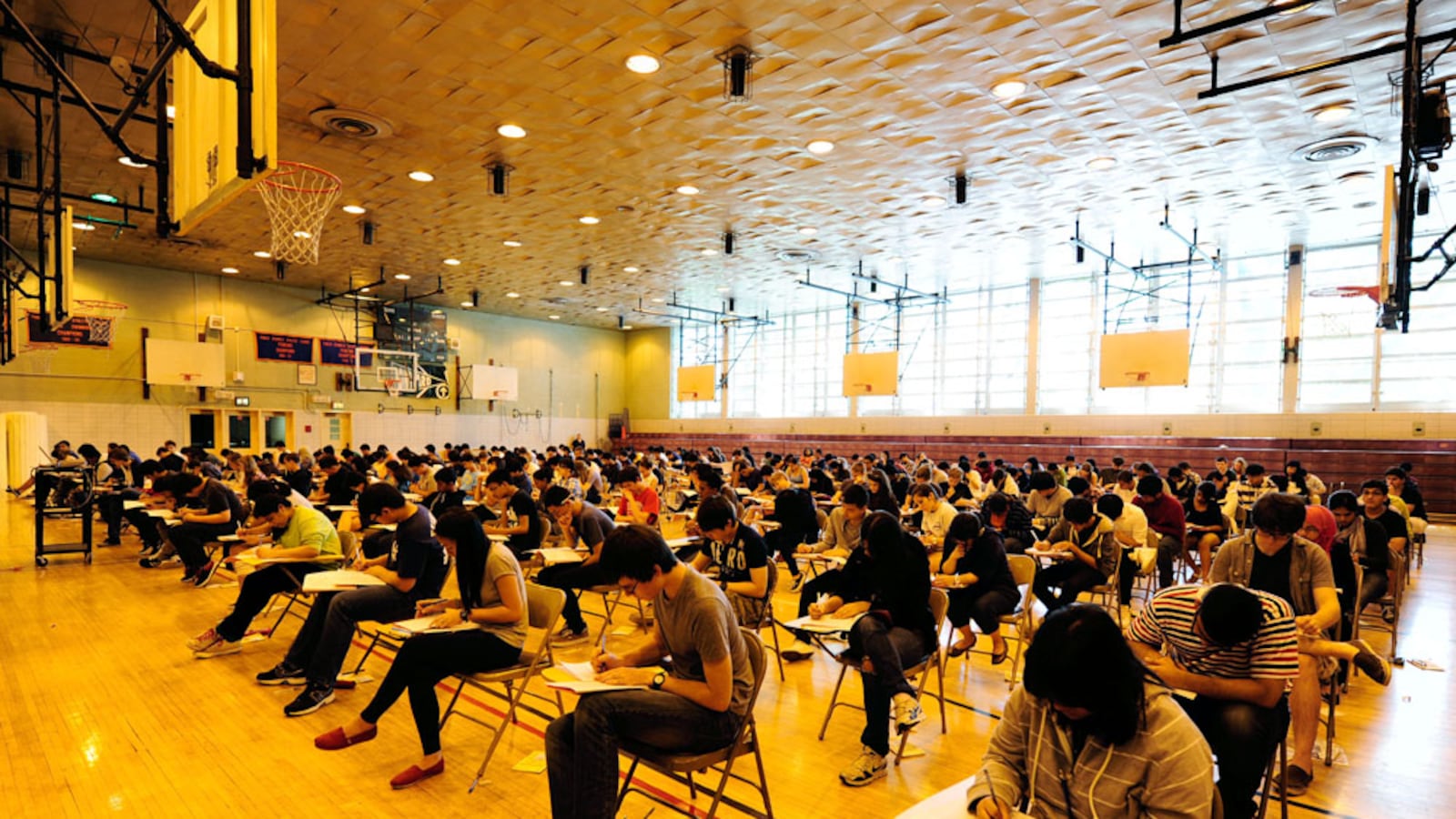

Students at dozens of middle schools across the city will take the Specialized High School Admissions Test on Thursday as part of an initiative to expand access for underrepresented students at the city’s specialized high schools. But data released by the education department shows that the program is not having its intended effect.

The initiative, started two years ago and expanded this admissions cycle, allows students to take the SHSAT during the school day, instead of on a weekend. The idea is that by offering the exam during school hours, and giving schools extra test preparation materials, black and Hispanic students and other underrepresented groups are more likely to take the test and have a shot at attending a specialized school.

Yet an analysis of the city data, which Chalkbeat requested, shows the program is overwhelmingly benefitting white and Asian students — groups that already dominate admissions to those schools.

At the 15 schools that administered the SHSAT during the school day last year, Asian students accounted for 68 percent of acceptances to attend specialized high schools. Overall, Asian students represented just over half of offers to specialized schools last year, which means that Asian students were even more likely to benefit from their schools offering the test during the day. (Just 16 percent of the city’s students are Asian.)

By contrast, Hispanic students accounted for just under 11 percent of offers at schools that administered the exam during the day last year, slightly better than the 6 percent who received offers during the overall testing process. Another 13 percent of offers went to white students. So few black students received offers through the program, the education department redacted the data citing privacy laws. Black and Hispanic students are nearly 67 percent of the city’s overall student body.

“What I call supply-side initiatives — more prep, better access to the test — the history of all these initiatives is they tend to get taken advantage of by the people who already do well on the tests,” said Lazar Treschan, youth policy director at the Community Service Society who has studied specialized high school admissions.

Despite those results, city officials are expanding the program significantly this year. Fifty middle schools across the city are offering the exam during the day on Thursday, up from 15 last year.

Will Mantell, an education department spokesman, defended the decision to expand the program. He noted that it has successfully boosted the number of students who take the SHSAT at participating schools by roughly 40 percent and pointed to figures that show the program has boosted the share of black, Hispanic, and low-income students who take the exam.

Hispanic students, for instance, made up 38 percent of the students who took the SHSAT during the school day last year; overall, just 23 percent of students who take the exam are Hispanic.

Mantell said the program “may show more impact as schools participate in the program for two or more years.”

In June, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a more aggressive push to integrate specialized high schools by eliminating the SHSAT as the sole entrance exam at eight specialized high schools, which include Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech, and Bronx Science. In its place, the city plans to offer a spot at a specialized school to the top 7 percent of students at every middle school — a move that officials say will significantly boost the share of black and Hispanic students at the schools.

“While it’s a start to see an increase in testers and offers at SHSAT School Day schools, the fact is: a single test shouldn’t determine a student’s future,” Mantell said in a statement.

Overall, just 10.4 percent of offers to eight specialized high school went to black and Hispanic students, even though they represent two-thirds of the city’s students, a number that hasn’t budged significantly in years.

Offering the SHSAT during the school day isn’t the only diversity initiative aimed at specialized high schools to fall flat. A separate program that offers admission to students who just missed the testing cutoff has also tended to benefit white and Asian students over black and Hispanic ones. (The city plans to expand that program, too, but with tweaks designed to enroll more underrepresented students.)

Some educators at schools that offer the SHSAT during the school day say there are benefits beyond increasing the number of students who get offers to specialized schools. At J.H.S. 118 in the Bronx, which is offering the exam during the school day Thursday, roughly 81 percent of students are black or Hispanic. Through the program, the school has also been able to offer SHSAT test prep to any student who wants it; before, it was limited to the school’s strongest students.

“We’re generally enthusiastic about what the program offers to our kids and what it tells our kids about who they are,” said Giulia Cox, the school’s principal, arguing it signals to a wider group of students that they have a shot at the most competitive high schools.

But even though the school boosted the number of students taking the exam by 38 percent (or 74 students) after offering the SHSAT during the day, only two more students received offers to a specialized school. Cox acknowledged the number of offers haven’t jumped much, but said the practice can still help students academically and give them a leg up in their test-taking skills.

“Maybe they don’t get an offer to a specialized high school,” she said, “but [they] are more prepared.”