My mother, three sisters, and I didn’t talk about politics much when I was growing up in Washington Heights. My parents, Mexican immigrants, couldn’t vote. But even if they could have, there was a common belief that our voices wouldn’t be heard. Todos son corruptos, my Mama reminded me as I tied my shoes on Tuesday to walk over to 158st and Amsterdam, where Community Health Academy of the Heights is located — my polling place. I was about to vote for the first time, a day after my 18th birthday.

Although this was the first election I have ever participated in, my journey to the ballot box began more than a year earlier, at New Heights Academy Charter School in Hamilton Heights. Before that, I hadn’t paid much attention to politics since elementary school. But starting in 2016, politics began, in the words of one of the survivors of the Parkland school shooting, to “hit home.”

Years before, when I was in elementary school at P.S. 28 Wright Brothers, I remember staring at a book in my classroom. On the cover was a drawing of a black girl in front of a podium. The book was about the first female president. At the time, I couldn’t believe there weren’t any ladies who wanted to be presidents and remember thinking, I’d just have to take on the job myself! Today, I know that the book was Grace for President! by Kelly Di Pucchio. As a 7-year old in the 2008 elections, I hoped Hillary Clinton would defeat Barack Obama —not because I preferred one’s politics to the other. I just really wanted a woman in charge. Now I don’t want to be the next female president anymore because I want America to have more female and diverse presidents as soon as possible. Still, into my early teens, I wasn’t a big fan of politics, because the subject struck me as boring and artificial. It always seemed to involve someone putting on a mask that an audience would like to see rather than a candidate presenting a genuine face to others.

Although I couldn’t yet vote, the 2016 election is when I really began to think about politics for the first time. Previously I’d been afraid to touch the subject, worried in part about the advice I’d seen on social media: Never talk about politics with friends unless you want to lose them. But after the election, my classmates at New Heights Academy Charter School, where a majority of the students were Latino, began to talk about politics every day in school. I am Mexican-American. I’d hear the same comments: Impeach Donald Trump! Oh, the Orange man! He doesn’t have real hair.

Even jokes about Mexicans being deported became normal after the president decided to make outwardly racist remarks. I often stayed silent. In my Advanced Placement U.S. History class, we would sometimes spend a whole hour talking about politics. And I still tuned out, thinking I didn’t have anything smart to say. Since I barely knew the importance of political parties, and the differences between electoral votes and popular votes, I spent my mornings in the A.P. course munching away on peanuts and daydreaming.

But then in one of those classes, a student made a derogatory comment about Mexicans working hard — the student thought it was a joke but it wasn’t funny. The teacher did not respond or object, and I remember feeling very disappointed. I knew teachers aren’t supposed to share their political views. But for a joke about a specific group of people, it hit home. One of the students who survived the Parkland shooting said that one does not get involved in a cause until it does hit home. This is the truth.

I remember paying more attention to the conversations we had in class after that. I was also frustrated that there was typically only one view being thrown around the room. So when a year later my AP Italian teacher shared with us voter-registration forms, I grabbed one. That teacher encouraged us to vote, and everyone became so excited, I became excited myself. Partly, I was afraid of missing out on something that everyone else was involved in. I was also thrilled to learn that the elections would take place on November 6th, the day after my 18th birthday — just in time for me to vote!

In addition, I became involved with a youth-led movement called Teens Take Charge. This coalition focuses on school integration in New York City. For the first time, I became exposed to policymakers. I became a photographer for the group and quickly became informed about different aspects of integration. Our work even landed us in front of Chancellor Carranza. More than ever, I came to realize that there were people at the forefront of change, expanding my horizons well beyond education policies.

I feared registering might be an arduous process, but for those thinking of doing it, it’s easy. I filled out the form in minutes and mailed it once I was home. Jorge Morales, a classmate who was a Policy Director of Teens Take Charge, Nadia Gallardo, another classmate, and I planned a walkout to protest gun violence on March 14th at our school. The students in Parkland Florida were very inspiring, and their activism reminded me of the work I and my friends were doing.

For the first time, I was in a like-minded group, which believed students shouldn’t have to wait until college or after to get involved in the policy work that affects their own education. Unfortunately in New York, because of the age when students enter school, most public school students have left high school before they turn 18. I was no exception. But I was lucky — because of my activism in high school, I was ready to vote when the time came, even though by that point I was a freshman at New York University.

In August, there was no escaping the “Go Vote” message. It started with a theatre production for the class of 2022, where the actors would stop midway to say, “And while you are at it, go register to vote.” There were signs in the library and in my residence hall. “NYU Votes” pins were handed out on every corner, and political conversations would arise in class.

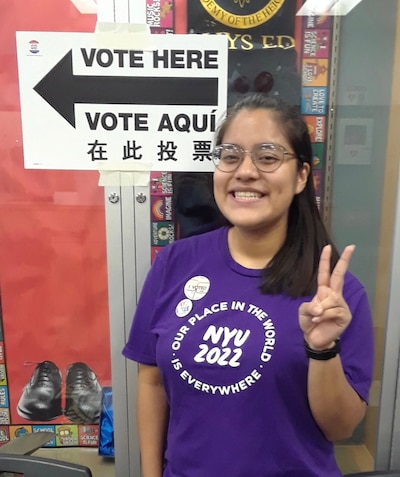

As a result, by the time November rolled around, I was more excited about voting than my own birthday on Monday. I had done some research on the candidates but wondered how much impact my vote would have. I voted because my work involves advocating for policy changes I believe in and to not vote, I would be contradicting the values behind this work. I wasn’t sure what to expect, but the experience was smooth. I went about my usual day, attending afternoon classes and then headed home to vote at the polling place in my Washington Heights neighborhood.

I decided I did not want to go alone. I called a friend who cannot yet vote, but who was willing to go with me. I was treated kindly and directed to my district’s desk. I wasn’t asked for identification, because I had provided a form that proved I had the necessary credentials when I registered. I proceeded to vote. Because I knew whom I would be voting for, the voting part was quite simple. However, I did some research beforehand about the referendum questions but I still worried: What if I vote incorrectly? Among my friends from high school with whom I’ve stayed in touch, roughly half voted and half did not. Those who did, I noticed, were involved in organizations or movements for social justice. Those who didn’t were not.

I was happy to see my community out voting: people who attend my church or who are parents of my friends. Washington Heights is a Latino neighborhood and to see Dominican moms and Ecuadorian teens reminded me that our voices could be heard. For this reason, I know I will vote again. Even as I avoid news channels or social media, politics shape your daily life. It’s the reason you live in the district you do. There was once a policy implemented one way or another. There’s a reason you attend the school you do. And there is a reason you use public transportation. Politics is behind a lot of the daily experiences we have, and voting to me means I get to shape those moments and help ensure I and others in my community get what we need. To remind myself that I own that kind of power — yes, that’s the best birthday present I could ever have.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.