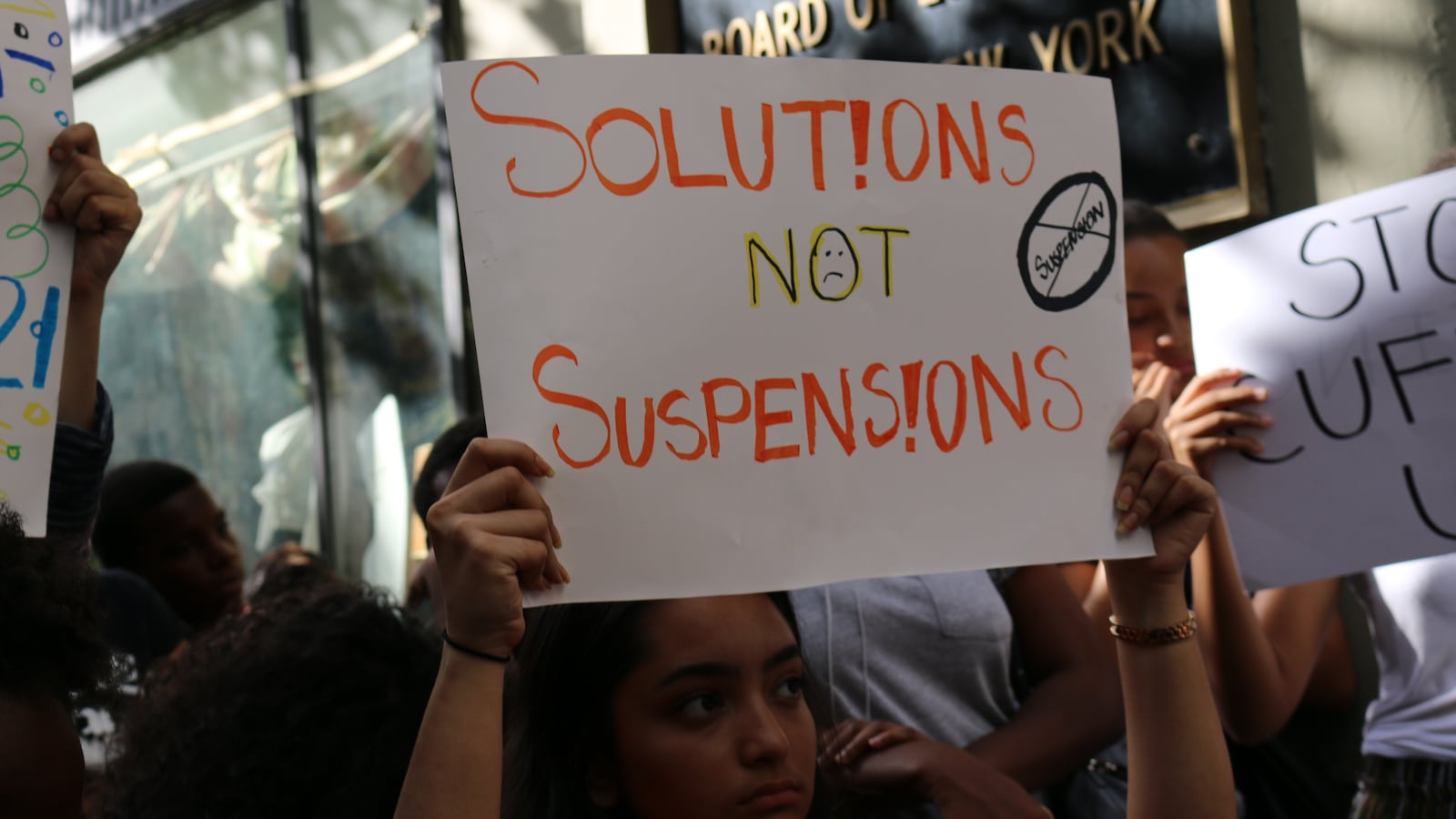

After successfully pressing Mayor Bill de Blasio to reduce the overall number of suspensions issued to New York City students, advocates are focusing on a new target: reducing the maximum length of suspensions — which can now last an entire school year.

In the wake of new discipline data that continue to show stark divides — including a report that found black students often receive longer suspensions than students from other racial groups for the same infractions — advocates and a group of city councilors argue the city must adopt a series of new reforms, including a cap on the length of suspensions to 20 days. Now, the education department is seriously considering a strict cap on the number of days a student can be suspended.

“The biggest thing we can’t wrap our head around is why you can suspend a student for 180 days,” said Tannya Benavides, a fourth grade teacher and volunteer with Organizing for Equity. The organization, which formed about a year ago, is conducting door-knocking campaigns in districts with high suspension rates to help create momentum for discipline reforms, including limits to the amount of time students can be removed from their classrooms.

Only a dozen city students were suspended for 180 days in the last school year, according to city data, but “superintendent suspensions,” which are issued for more serious infractions and can run from six days through the whole school year, were handed out more than 10,000 times. About a quarter of those long-term suspensions were for 30 days of more, meaning that thousands of students were kicked out of their schools for at least a month last year.

Those suspensions were heavily tilted toward students of color. Black students, who make up 26 percent of the city’s student body, received 52 percent of last year’s superintendent suspensions. White students — who make up 15 percent of students — received 6 percent of the long-term suspensions.

In response to recent advocacy, both City Hall and the chancellor say they are eyeing changes to the discipline code, essentially the manual that dictates how educators respond to student misbehavior, including the length of suspensions.

Advocacy efforts in recent years have broadly focused on decreasing suspensions overall, an effort that has been largely successful. De Blasio has implemented a series of school discipline reforms that have made it harder to suspend students for certain infractions, and dramatically reduced suspensions for the city’s youngest students. Overall, suspensions have fallen by roughly 32 percent since he took office.

But the number of lengthier suspensions has not fallen as precipitously.

Students who receive superintendent suspensions — which can be issued for infractions ranging from minor shoving to bringing a weapon to school — have the right to a formal hearing and are removed from their school to one of the city’s 37 “Alternative Learning Centers” where students are expected to continue their studies.

Multiple advocates said that even if students continue to have access to instruction, lengthy suspensions can have serious consequences, setting students on a path to falling behind in school and dropping out. A recent study, focusing on New York City, found that suspensions contribute to students passing fewer classes, increasing their risk of dropping out, and lowering the odds of graduating.

“Our experience has been with young people who are already struggling, that the long-term suspension compounds those struggles,” said Kesi Foster, who has worked closely with students in the school discipline system and is a coordinator with the advocacy group Make the Road New York.

A group of city councilors penned a letter to de Blasio and Carranza last month seeking a series of discipline policy changes, including the elimination of arrests and summonses for low-level offenses and eliminating suspensions entirely for “insubordination” — a category that advocates argue is subjective and can invite bias. But at the top of their list was a demand to limit the length of suspensions, and shrink the range of days a student can be suspended in several categories.

Top city officials now say they are revisiting changes to discipline policy, which has already been edited under the current administration.

Jaclyn Rothenberg, a de Blasio spokeswoman, said the mayor has asked schools Chancellor Richard Carranza “to take a hard look at our current discipline code.”

“The mayor is concerned with the length of our suspensions coupled with the suspension trends in some of our most vulnerable communities,” Rothenberg said in a statement.

In a brief interview last week, Carranza suggested that he is considering a wide range of possible changes, saying there are “no sacred cows” in the city’s discipline policy.

But previous efforts to overhaul the discipline code have been controversial. Some educators, union officials and school leaders have resisted policies that limit their power to suspend students, arguing that is has lead to more chaotic school environments. And while the city has made some efforts to train educators on “restorative” approaches — such as mediation, in which school adults or peers encourage students to talk through conflicts — critics argue those efforts have not reached enough schools.

Still, advocates hope to take advantage of the latest signal that city officials are open to a new set of policy changes.

“It’s getting new attention from the [education department]” said Dawn Yuster, the School Justice Project director at Advocates for Children, an advocacy organization that has pushed for school discipline reform. “We see that we can get traction now, so we’re looking at as many openings as we can.”