Manhattan parents expressed outrage Monday night over Mayor Bill de Blasio’s controversial plan to overhaul admissions at some of the most sought-after high schools in New York City.

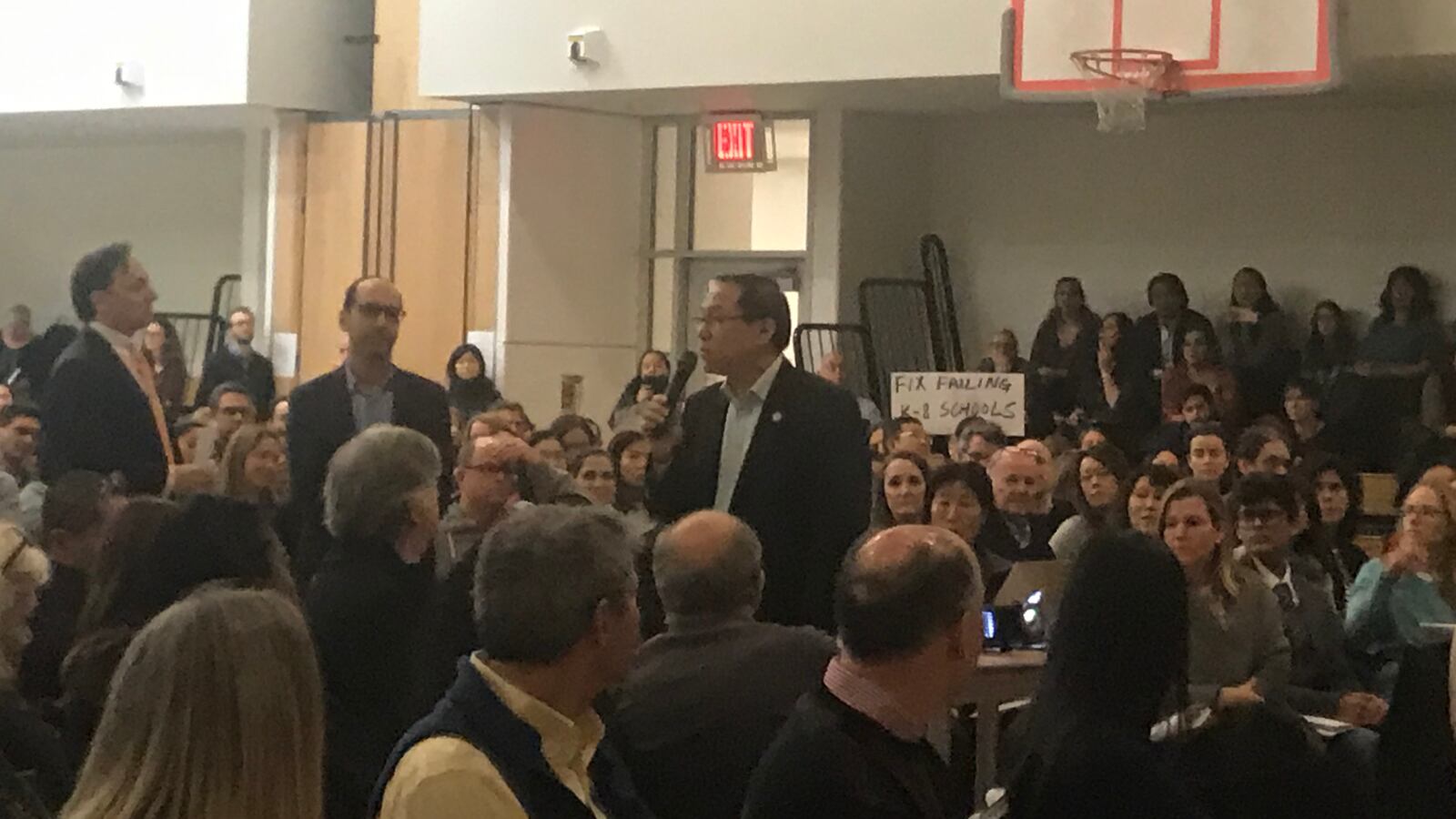

At least 300 people attended District 2’s Community Education Council meeting, where Deputy Chancellor Josh Wallack formally presented the city’s plan to get rid of the test that middle school students can take to gain admission to eight of the city’s specialized high schools.

In June, De Blasio announced his plan to phase out the test and instead guarantee a spot to the top 7 percent of students at every city middle school, using multiple measures including their GPAs and performance on state tests. Because the city’s middle schools are starkly segregated by race, the proposal would significantly increase the proportion of black and Hispanic students who are admitted. For the proposal to go through, it would require a change in state law.

Black or Hispanic students make up 10 percent of the enrollment at the city’s specialized high schools but represent almost 70 percent of students citywide. Critics have said basing admission on a single test advantages students who can afford test prep or are keenly aware of how important the exam is.

But many parents pushed back, including Asian families who have lobbied to keep the test (though one group supports getting rid of the exam). Asian students represent about 62 percent of students at the specialized high schools and just 16 percent citywide.

In District 2, the plan has sparked hot debate. The Manhattan district, which stretches from the Upper East Side and through Soho to Tribeca, enrolls just 8 percent of the city’s eighth graders but accounts for almost 13 percent of admissions to specialized high schools.

After Wallack’s presentation, at least 30 parents spoke out against the plan, cheered each other on and booed Wallack. When a parent asked the crowd to raise their hands if they supported the proposal, not a single hand was visible (though one parent did speak in support of the plan). Several parents argued the plan would offer admission to students who are not qualified for the schools’ rigorous curriculum.

According to education department projections, the plan would not significantly affect the average GPA and state test scores of admitted students. And even among selective public high schools nationwide, the reliance of the city’s specialized high schools on a single, high-stakes exam for admission is highly unusual and has contributed, critics say, to New York City’s being one of the most segregated school systems in the country.

Others, who acknowledged how segregated the system is, urged more investment in black and Hispanic students to improve their academic opportunities and characterized the plan as a well-intended proposal that will flop. Some said the plan will create a “snake pit” among middle schoolers, who will resort to vicious competition.

“Put yourself in the place of the black and Hispanic kids who are there because of counting methods,” said Jon Haidt, a professor of social psychology at New York University, who has a seventh-grader at The New York City Lab School for Collaborative Studies.

Alan Siegel, also an NYU professor of computer science, said, “You people are proposing a grand experiment on our children.”

The continued backlash against the plan shows just how challenging the fight will be for de Blasio, who has only recently pushed for admission changes at specialized schools despite promising to do so when he first ran for mayor. Key officials, including local politicians and union leaders have not lined up in support, and it’s unclear whether state lawmakers will get behind the plan.

Wallack repeated the city’s intention for the proposal in between clusters of speakers, at one point saying, “We all share the same goals, and no one, of course, is trying to create a plan that will set students up to fail.” One parent yelled out, “Liar,” a couple of times in response. Another parent repeatedly shouted that the test is a fair solution. The meeting, which started at 6:30 p.m., lasted until 10 p.m — because the meeting space was reserved until then.

Even the Community Education Council was split on the issue. Vice President Maud Maron proposed a resolution that, in part, asks the city education department to pull its support of the proposal and allow more community engagement before anything goes forward. The language is sharply critical of the plan, a view some members of the council didn’t appear to share.

Although Maron found some support, others thought the language problematic. Council member Eric Goldberg said he heard “insane obsessions with selection and assessment” during the meeting, and that he didn’t want to vote for something that “denies the essential truth that we have a segregated school system.”

With a 5-5 tie vote, the resolution did not pass.

Alex Zimmerman contributed to this report.