On Wednesday, state lawmakers will head back to Albany for what could be a historic 2019 session, with the first fully Democratic-led state government since 2010.

That new political makeup in the Senate will likely change the course for state education policy: What can we expect for mayoral control of city schools? How bleak is the future of charter school openings? Will lawmakers move to get rid of the admissions test for New York City’s specialized high schools, or will they push the issue off for another year?

Here’s what to expect over the next few months.

SHSAT

New York City’s controversial proposal to diversify its most elite high schools needs state approval — specifically, the part of the plan that calls to eliminate the specialized high school admissions test, known in short as the SHSAT.

Last June, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a plan that would instead grant admission to the top 7 percent of middle school students. He swiftly earned a mix of backlash from families who believe the test is the best method of admissions and support from those who see his proposal as an important step toward integration.

The plan would usher more black and Hispanic students into the city’s eight most selective high schools. Many parents of white and Asian students, who represent the majority in these schools, have called the test “race blind” and argued that the city must instead properly educate all students earlier so they’re prepared to take the test. Supporters of the plan say that preparation for high-stakes testing is usually only accessible to more affluent families who have the time and resources.

Some advocates for keeping the test have decided to invest in lobbyists. The alumni foundation for Bronx High School of Science, one of the elite high schools, signed a $96,000 contract with lobbying firm Bolton-St. John, according to public filings. Brooklyn Tech Alumni Foundation, which renewed a $120,000 contract with firm Yoswein, has lobbied for the test since at least September 2017, filings show.

Another group called the Scholastic Merit Fund, comprised of more advocates who want to preserve the test, hired Parkside Group LLC for $60,000 to lobby in support of the test.

Sen. Shelley Mayer, a Yonkers Democrat who will chair the Senate education committee, said she has “serious process concerns” about how de Blasio’s office handled the rollout of this plan, but she declined to comment beyond that. She deferred to newly elected Queens senator John Liu, a Democrat who will chair the New York City Senate education subcommittee, who says he acknowledges the city’s segregation problem but feels the Asian community should have been consulted.

Larry Cary, president of the Brooklyn Tech Alumni Foundation, said his group supports efforts to diversify the elite high schools through stronger enrichment programs, but scrapping the test is not the answer. He says his group will “actively” engage lawmakers “about what the problem really is,” but he’s not sure it will even matter this year.

“It remains to be seen in all of the issues — and there are huge issues facing the legislature now — what kind of priority this issue will take,” Cary said in an interview late last year with Chalkbeat.

Teacher evaluations

Senate Democrats will prioritize untying certain state assessments from teacher evaluations, Mayer said. Like many opponents to the current law governing teacher evaluations, Mayer called it a “terrible system” for judging teachers, ultimately hurting students and parents.

Mayer expects Democrats to act quickly and believes support exists in both chambers. A similar bill to untether tests from evaluations sailed through the Assembly last year, but died in the Senate. The new make-up of the Senate could change that this year.

The state Board of Regents will soon formally extend a moratorium that separates evaluations from how students score on elementary English and math assessments. In the meantime, the board is planning to assemble work groups that will explore how to best evaluate teachers.

From these work groups, state education officials want to provide guidance for lawmakers as they make policy decisions on assessments and evaluations. Mayer said she welcomes the Regents’ input, but she’s also not willing to wait past this session.

“I think we should go right ahead,” Mayer said. “Let’s get this bill done.”

In December, State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia told reporters that she hadn’t received a signal from lawmakers on whether they’ll wait for the Regents’ recommendations.

“They certainly know the work we’ve done and have started, and we have shared with them that this is our plan,” Elia said. “If they are in a position to use that, then that’s great. And if that doesn’t happen, that’s certainly up to them.”

Mayoral control

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s control of city schools expires on June 30, so it’s the issue with perhaps the most pressing deadline.

Mayoral control, which replaced a fractured system of boards of elected officials, reaches back to Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration in 2002. State lawmakers must decide whether it should be extended past the expiration date written into law, and for how long.

It’s “weighing heavily” on state lawmakers, especially since it “has been thrown around as a political football for so long,” Sen. Liu said in an interview with Chalkbeat last month.

With de Blasio’s political party at the wheel, he is likely to get the extension he needs without fighting the ugly political battle that bubbled up in past years with Republicans and Gov. Andrew Cuomo. But there could be some pushback over what mayoral control will look like in the future.

Liu and newly elected Sen. Robert Jackson, another former New York City politician, have suggested that the nature of de Blasio’s control over schools could be the real focal point.

“I don’t want to call it control,” Jackson told City and State New York. “Let’s call it mayoral authority with oversight. Oversight by the City Council, oversight by the state of New York, not control.”

City Hall officials did not answer questions about what de Blasio is expecting as the session starts, but asserted that mayoral control is in the best interest of New Yorkers.

“Mayoral control is the reason why we have record high graduation rates and college enrollment, record low dropout rates and a Pre-K seat for every four year old in New York City,” said Jaclyn Rothenberg, a spokeswoman for de Blasio. “This policy empowers families and strengthens school communities and allows us to build on our record progress.”

School funding

Expect a tough fight over education funding in this year’s budget proposal, Mayer said.

Backed with a majority, Mayer expects a “very aggressive response” from Senate Democrats for more education dollars, especially after Gov. Cuomo’s repeated rejection of a formula that is supposed to provide extra dollars for high-needs schools throughout the state.

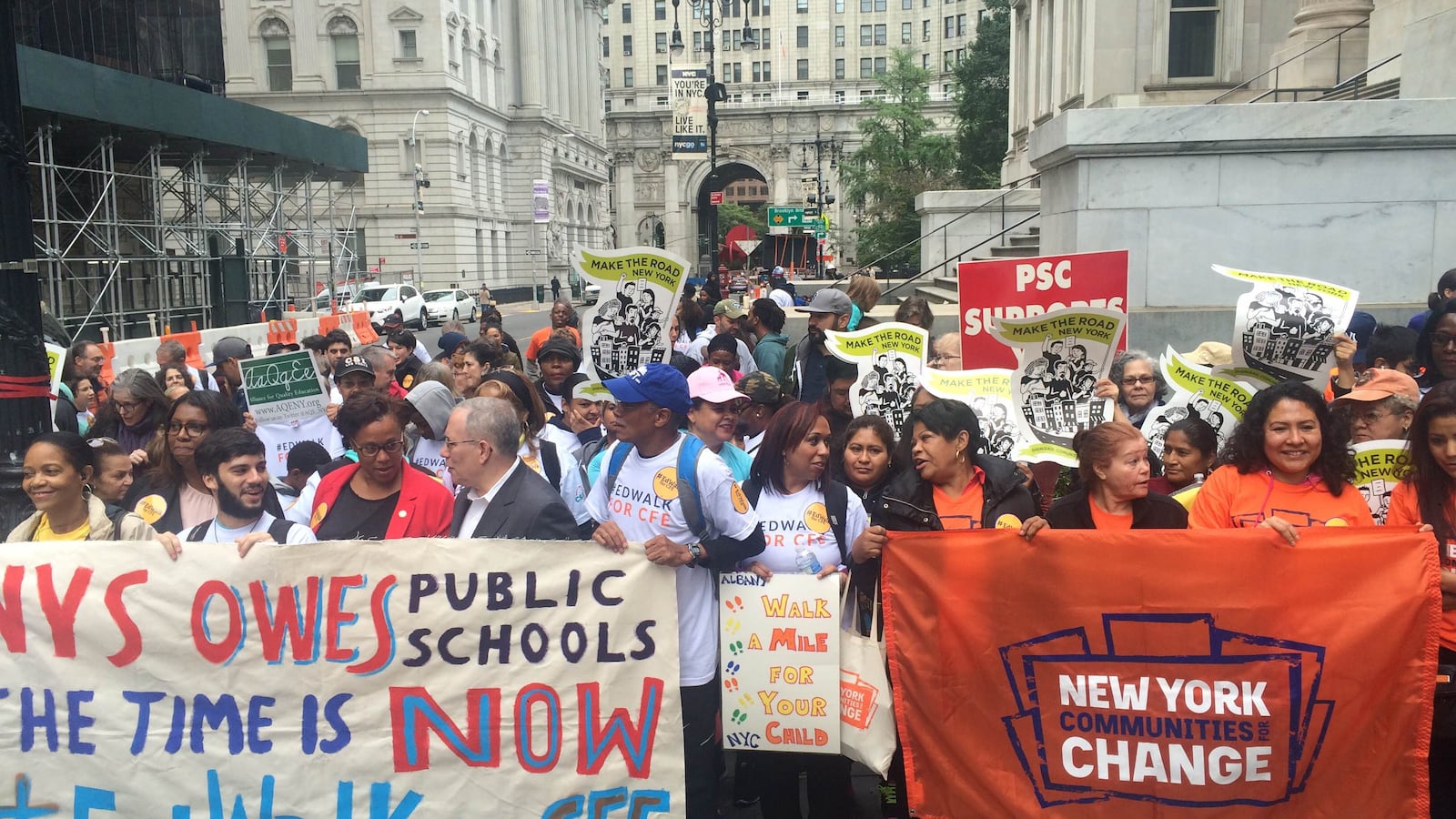

The formula, called foundation aid, was the result of a 1993 lawsuit that argued the state wasn’t providing enough money for schools. The formula sent extra dollars to high-needs schools until the recession set in. Now, advocates and state education officials contend that districts with the most vulnerable students are owed $4 billion in foundation aid.

In a speech and on a radio program, Cuomo called the lawsuit a “ghost of the past,” and compared people still pushing for foundation aid dollars to those “who would say the world is flat.”

Cuomo’s comments angered funding advocates and progressive lawmakers, who campaigned on boosting education funding. State education policymakers have requested an almost $5 billion phase-in of foundation aid money (adjusting for inflation) over the next three years. Sen. Jackson, the former New York City councilman, was one of the lead plaintiffs on the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit that eventually created foundation aid. In a statement last month, he and a few new Democrats rejected Cuomo’s view.

“The outcome of CFE’s lawsuit still remains clear: New York state is legally obligated to release billions of dollars in funding to our schools, and the foundation aid formula should be used to allocate those funds,” Jackson said. “Burying this obligation and claiming that it’s ‘a ghost of the past’ doesn’t make it go away—it makes a bad problem worse.”

Mayer, who also believes districts are still owed foundation aid, said there will likely be budget negotiations to revamp the formula so that it uses more updated data when counting how many high-needs students are in districts throughout the state.

Charter schools

After November’s elections, charter school advocates lost some of their biggest cheerleaders in state government— several Senate Republicans and a group of Democrats who broke with their party.

Now, new and more public-school-focused lawmakers probably won’t have the appetite to expand the cap on how many charter schools can open in New York. There are just seven slots left for New York City, so for advocates of charter schools, the issue is essential for their expansion efforts.

Some charter advocates told Chalkbeat that their main strategy will now have to be grassroots organizing — so that new progressive lawmakers who campaigned against charters can hear the “drumbeat” from constituents who want different school options.

In the meantime, it’s possible the new Democratic majority will push for stronger regulation of charter schools and maintaining the cap — both things Mayer supports.

“Our focus has to be on primarily on something for public schools,” Mayer said, adding New York City and her own community in Yonkers are “desperately” in need of resources.

“My door is open to the charter school community and I look forward to hearing what their concerns are. They educate a lot of kids — I’m very mindful of that — but we can’t pretend we’re starting on an equal playing field.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story incorrectly said the Scholastic Merit Fund and Brooklyn Tech alumni foundation were lobbying against the SHSAT.