It’s getting harder and harder for Michelle Paige to hold onto pre-K teachers in the community-based centers she oversees. The problem: her teachers keep leaving in search of the higher paychecks available in New York City’s own pre-K programs, where they can earn thousands more every year.

“It’s at a crisis level,” said Paige, the associate executive director of early childhood programs at the social services organization University Settlement. “You are really looking at depleting a workforce.”

The pay gulf isn’t getting any better. A new United Federation of Teachers contract takes effect on Thursday, boosting salaries for some teachers while continuing to leave those who work in community programs significantly behind.

Advocates say the city has a fresh opportunity to address the disparity. The education department is set to take responsibility for publicly-funded early childhood programs — a bid to create a more streamlined system from birth through high school graduation. Providers say one major way to build cohesion is to make sure everyone is paid fairly.

Providers such as Paige say the pay disparity is among the greatest challenges they face ever since New York City began a rapid roll out of free pre-K, which has made it difficult to keep teachers who now have more opportunities to earn better pay. After making the program available for all 4-year-olds, Mayor Bill de Blasio is rushing to expand his signature education effort to serve the city’s 3-year-olds as well.

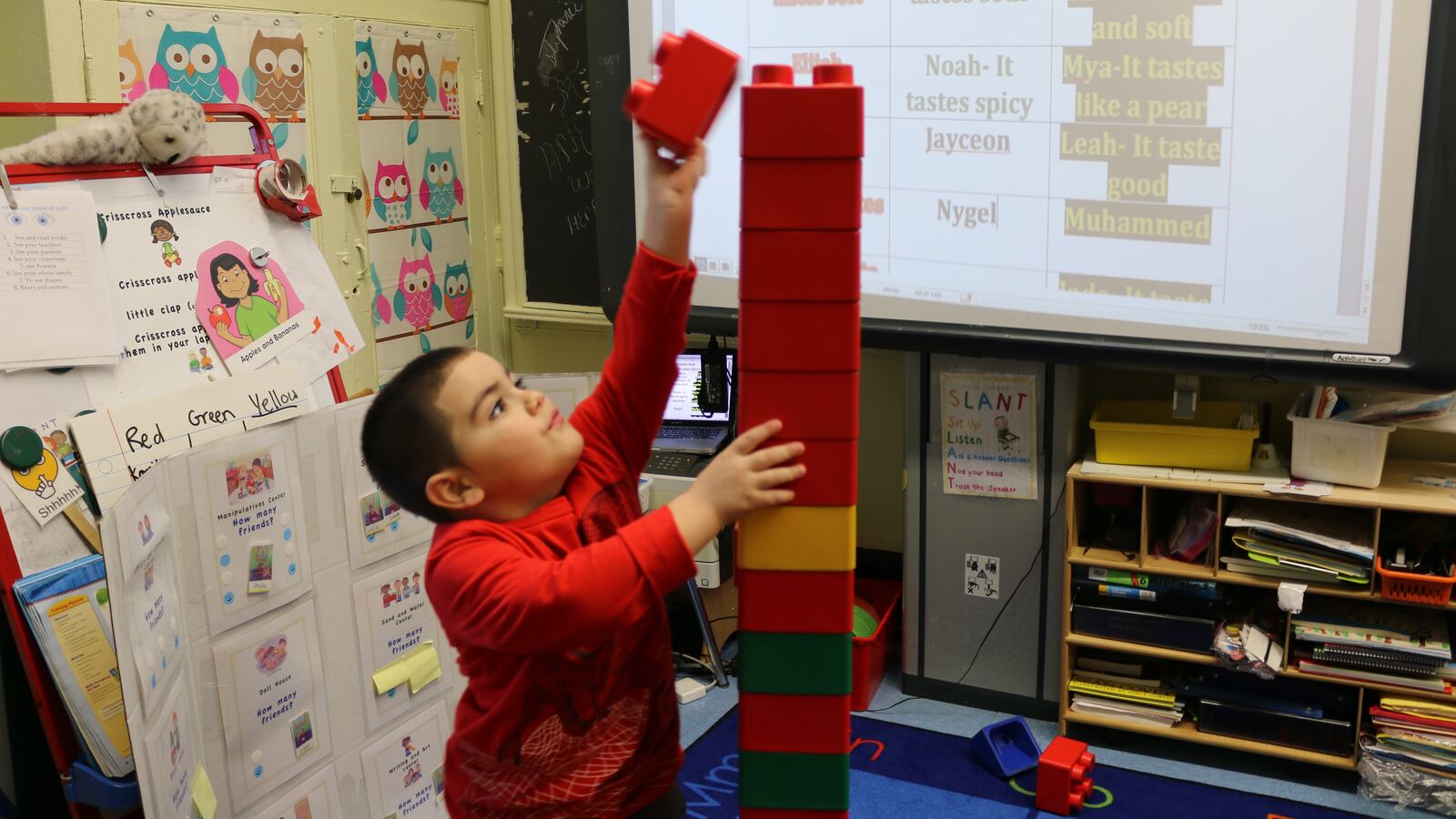

In order to enroll so many children, New York City offers pre-K in public school settings and also contracts with community-based organizations, which enroll about 60 percent of all pre-K students. Teachers in either setting are required to have the same degrees and credentials.

An education department official on Wednesday praised these community-based providers for the “critical role” they play and and pledged the department would “continue to work with our providers to recruit, retain, and grow a talented workforce.”

But those in district-run classrooms earn up to 60 percent more, and often work fewer hours a day, and a significantly shorter school year.

Reasons for the pay disparity are many. Teachers in city-run classrooms belong to the UFT, the largest local in the country — and enjoy comparable clout. Pre-K teachers in other work settings are represented by a patchwork of locals.

Funding streams for early childhood programs are also often attached to particular age groups — for example, the city’s Pre-K for All program serves 4-year-olds exclusively — or based on family need. As a result, teachers who work just down the hallway from each other can earn varying salaries and benefits.

“You have disparity within your own organization. And your hands are tied,” Paige said.

Caitlin McLean, who studies the early childhood workforce, sees other reasons for the gap. She says the skills needed to care for young children and early childhood care generally are undervalued — along with the women, often of color, who perform this work.

“But the brain science says that, if anything, we need the most trained, well-qualified people working with the youngest kids because that’s what sets you on your trajectory of learning for K-12 and beyond,” said McLean, a research specialist at the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, Berkeley.

After a decade without a pay raise, teachers in community organizations won a boost in their 2016 contract. Over the four-year term of that agreement, salaries will increase from $40,000 to $50,000 for certified teachers with a master’s degree. Teachers with lower degrees will still earn far more under the new UFT contract, which will push starting salaries up to more than $59,000 by 2020.

Other provisions of the contract provide pay incentives for teachers who work in hard-to-fill positions in schools and neighborhoods that struggle with high staff turnover — a benefit not available to teachers in community-based organizations that have fought the same challenges.

“The early education teachers in CBOs have been serving these communities for decades, and it just kind of made the pay disparity issue all the more real,” said Jennifer March, the executive director of the Citizens Committee for Children of New York, an advocacy organization.

March and other advocates hope the pending transition of early childhood contracts to education department oversight will include a new infusion of money to help bring parity to their teachers’ paychecks.

“I think it’s really a question about political will,” March said.

So far, the education department has signaled only that it will continue its existing efforts to help centers recruit and retain teachers, such as a $3,500 incentive for pre-K teachers who stay in community programs.

“We’re supposed to be all one system,” Paige said. “But with that, there has to be a very conscious decision to bring the workforce up to a salary that’s truly commensurate with the work that they’re doing.”