Plans to integrate New York City’s specialized high schools can move forward as a lawsuit targeting the admissions changes winds through court, a judge ruled on Monday.

The judge denied a temporary injunction meant to halt the city’s expansion of the Discovery program, which offers admission to students who scored below the cutoff on the exam that is the sole entrance criteria for specialized high schools. For now, the judge’s ruling will also enable the city to change who is eligible for Discovery, “which may in turn increase racial diversity” at the schools, the city argued in legal filings.

The decision came in time for the education department to begin informing students of their high school placement offers in March.

Parents and community organizations filed suit in December against the city’s plans, saying they violate the rights of Asian students.

But in his ruling, Judge Edgardo Ramos wrote that the plaintiffs were “not likely to succeed in showing discriminatory intent,” nor to prove their claims that the city’s changes violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Rather, Ramos wrote he believes “it is more likely than not that achieving racially diverse classrooms will be shown to be a compelling government interest.”

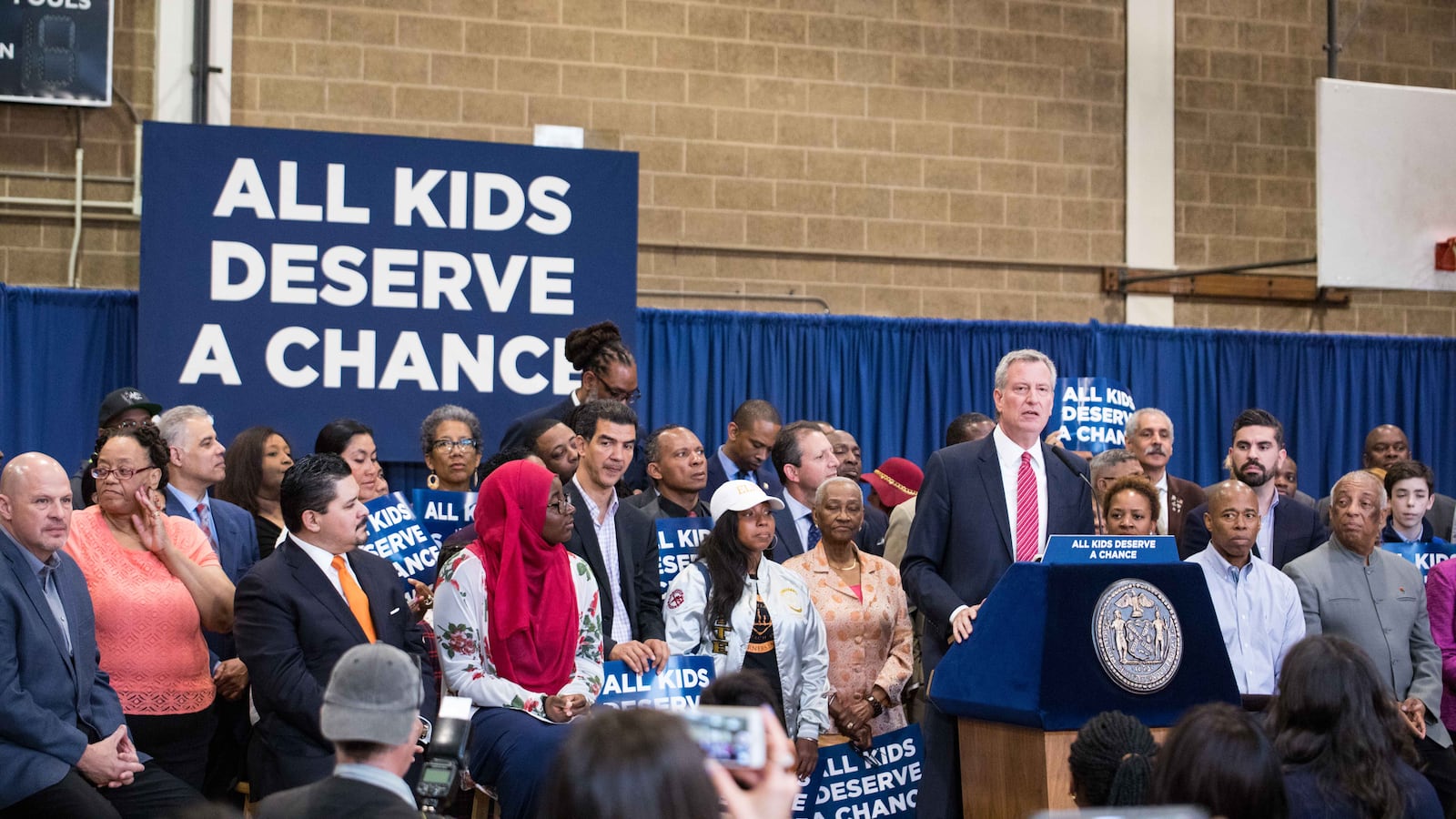

The Discovery changes are just one piece of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s recent push to integrate specialized high schools, where Asian students make up 62 percent of enrollment but black and Hispanic students constitute only 10 percent. Citywide, 16 percent of students are Asian and almost 70 percent are black and Hispanic. The mayor has also launched a lobbying effort to eliminate the entrance exam, which would require a change in state law, and instead offer admission to top students in every public middle school.

In previous legal filings, the city has said it will offer 528 spots through the Discovery program, a significant increase over the 250 students who entered through the program this year. With more seats dedicated to Discovery, the cutoff for admission based on the specialized high school exam alone (for students who don’t qualify under Discovery) is expected to be 486 out of around 700 — about five points higher than if the expansion were halted.

The judge wrote that the city’s changes to Discovery “are exactly the sort of alternative, race-neutral means to increase racial diversity,” that courts have suggested governments may use.

But Joshua Thompson, a senior attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, the firm representing the plaintiffs in the case, said Asian students will suffer because of the city’s moves.

“Absent the injunction, hundreds of Asian-American kids will be denied the opportunity to attend life-changing schools solely because they are from the ‘wrong’ race,” he said in an emailed statement.

Lawyers representing the city had asked for a ruling by Feb. 25 in order to send high school admissions offers to families by March 18, which is about two weeks later than originally planned. In New York City, students must apply to high school and are matched to their top choices, a process that is often stressful for families vying for the most sought-after schools.

“It has been a confusing, anxiety-ridden, complicated year in admissions for parents,” said Robin Aronow, a consultant who helps families navigate the application process through her company, School Search NYC.

Aronow said a delay in admissions could be especially problematic for parents who are considering private schools, many of which have set a March 14 date to accept offers.

“The longer it takes, the more anxious everyone becomes,” she said. “ They want to know how it’s going to directly affect their kid’s admissions.”