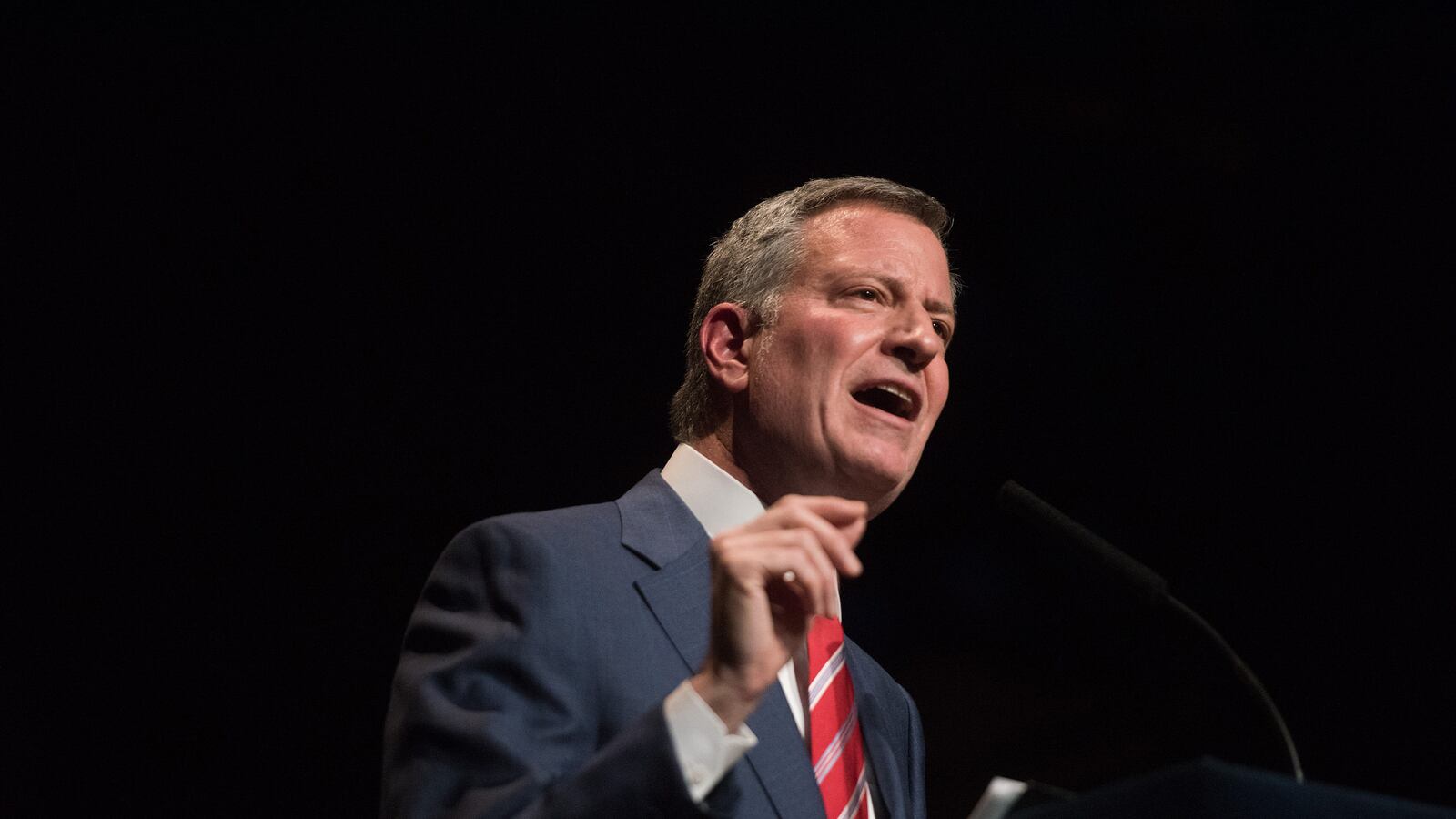

Days after new statistics showed the city’s elite high schools continue to admit few black and Hispanic students, Mayor Bill de Blasio said the admissions system “has perpetuated massive segregation” — a remarkable shift in rhetoric for a mayor who has avoided the word “segregation” to describe the city’s schools.

“People want to see change,” de Blasio said in response to a question about admissions to the city’s specialized high schools on WNYC’s Brian Lehrer Show. “That’s why we’re doing something bold here, and we’re saying we’re not going to live by this old system that has perpetuated massive segregation — not just segregation, massive segregation.”

The dramatic shift in tone comes amid renewed debate about his plan to overhaul admissions at eight elite high schools, which currently admit students based on a single exam. On Monday, new data showed that just over 10 percent of offers to the elite schools this year went to black or Hispanic students, even though they represent roughly 70 percent of the city’s enrollment. Just seven black students, out of 895 offers, got into Stuyvesant High School, a statistic that has captured national attention.

For years, de Blasio has avoided the words “integration” or “segregation” — even though the city’s schools are among the most segregated in the country. Those words can’t be found in the mayor’s “diversity” plan, released in June 2017. And de Blasio has suggested segregation is an intractable problem — once saying he can’t “wipe away 400 years of American history.”

So why the sudden shift in language?

One clear reason is the mayor needs to ratchet up pressure on state lawmakers, who have control over the plan’s fate, but have demonstrated little interest in taking action. Even some of the mayor’s supporters say it has dim chances in Albany. (Though for the first time, after the new numbers were released, lawmakers called for hearings and community forums on the issue.)

Under the mayor’s proposal, the top 7 percent of students citywide would gain admission to a specialized school, scrapping the test entirely. De Blasio’s use of stronger language could create more pressure on lawmakers to act, since the the single-test admissions process is written into state law. A “massive segregation” problem is harder to ignore than a “diversity” plan.

He’s also mulling a run for president and may sense an opportunity to be seen fighting for integration during a Democratic primary where racial equity and class are broad themes. There could be a big political upside in being on what de Blasio sees as the right side of a civil rights issue.

And his schools Chancellor, Richard Carranza, repeatedly uses the words segregation, which has drawn attention to the mayor’s insistence on talking about “diversity” instead.

Still, adopting stronger language could create more pressure on the mayor to address segregation beyond eight of the city’s 1,800 public schools. Whether he has the appetite to wade into a broader debate about the system as a whole remains to be seen.

Last month, a task force convened by de Blasio issued a series of modest recommendations on how to integrate the city’s schools. The mayor has yet to comment on them.