Fatema Khanum could read English but barely speak it when she enrolled at ELLIS Preparatory Academy in the Bronx, a public high school that serves new immigrants.

Arriving in New York City from Bangladesh when she was 17, Khanum found it “overwhelming” to chat with her peers and teachers, she said, let alone write essays and complete homework. Two years later, she speaks English with ease, and she credits her teachers for nudging her toward after-school homework sessions and extracurricular activities and making sure she socialized with students who don’t look like her. And most importantly, she said, even though her teachers didn’t speak her native language, they were patient with her as she learned English.

“They were like parents to us because they were pushing us to move forward,” Khanum said.

It’s these teaching skills that New York state education officials want to bolster statewide to address the state’s growing English language learner population — as graduation rates for these students remain chronically low.

Right now, students studying to be teachers in New York are required to spend six semester hours learning about language acquisition and literacy. Last month, state education policymakers proposed requiring teacher preparation programs to dedicate three of those hours to how English language learners learn and acquire language.

“Courses in language acquisition and literacy development will help young teachers meet the particular needs of these students and build on the success we are seeing in New York’s ELL programs,” said Chancellor Betty Rosa in a press release.

Whether this change is enough to address the significant challenges that immigrant students face remains to be seen. Last June, just 29 percent of English language learners across the state and 35 percent in New York City graduated from high school on time, though these rates have gone up slightly in recent years. In New York City, just 10 percent of English language learners scored proficient on their third to eighth-grade reading state exams last year — up from 6 percent the year before (though because of changes to the assessments, state officials have cautioned against making comparisons).

Still, observers say the proposed new requirements suggest the state is taking a closer look at the needs of these students, building on rules passed five years ago that require 15 percent of professional development hours to focus on best approaches to teaching English language learners.

The state’s proposals would apply to 94 teacher preparation programs at colleges that offer certificates in early childhood, childhood, middle, and adolescence education, state education officials said. It would also extend to those studying to be teachers of students with disabilities, teachers of English to speakers of other languages, and library media specialists. If adopted, the requirement wouldn’t take effect until September 2022, a lag that the state says would allow prep programs to tweak their curriculum.

Some city colleges have already recognized the need to pay this student population more attention. New York University bakes lessons on educating English language learners into its curriculum for aspiring teachers in a way that exceeds what the Regents have proposed, said Diana Turk, director of teacher education and associate professor of teaching and learning at NYU Steinhardt.

“We’re glad New York is catching up,” Turk said with a laugh.

The school, Turk said, even takes special care with their words — faculty use the phrase “emergent bilinguals” because “it’s an asset-based term” that doesn’t assume students are lacking something. And its programs emphasize factors beyond the curriculum, such as how teachers should communicate with family members of students from different backgrounds, and when is it OK to rely on different mediums to communicate, such as Google Translate.

Additionally, the school’s teacher residency master’s program — which offers aspiring teachers a one-year classroom experience — has focused on serving vulnerable students, such as students with disabilities and immigrant students, Turk said.

The program recently received a $481,727 grant over the next two years from the Walton Family Foundation to bolster its residency program. The Foundation also awarded $500,000 to New York City’s Bank Street College of Education, which will go toward a similar program for those interested in certificates for TESOL — Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. (Chalkbeat receives support from The Walton Family Foundation.)

Bank Street created the program after hearing from those who work in New York City schools about better options for training TESOL teachers, said Shael Suransky, president of Bank Street. Student teachers will get placed in schools such as ELLIS Prep and receive a $20,000 stipend, Suransky said. That sort of exposure is important, especially for aspiring teachers who are interested in such a vulnerable student population, Suransky said. In general, Suransky said Bank Street likely already satisfies the requirements proposed by the Regents, but they’ll have to review to make sure.

“We also believe really strongly that if you’re going to successfully change outcomes for English Language Learners in New York, you need to create a curriculum for those students that is attuned to their developmental needs,” Suransky said.

While the state requirements are a welcome change, some observers say there must be more support for aspiring teachers when they get to run their own classroom — especially those who don’t have certificates in teaching English as a second language. Suransky, former senior deputy chancellor for the city education department, said city officials should “move beyond sort of a compliance approach” in meeting state professional development requirements and create more curriculum support for general education teachers, who spend a lot of time with students learning English.

The city education department has a team in each borough office that provides schools with instructional coaching on teaching English language learners, according to an education department official. Each team — comprised of a director, coaches, and service administrators — operates differently based on what each network of schools needs.

The department also offers a program in which teachers can earn a bilingual extension of their New York State teacher certification through university partnerships.

“We’re committed to providing the best education for our multilingual learners,” said Danielle Filson, a spokeswoman for the city education department, in a statement. “We offer high-quality training for our teachers and are building on this work through our new Division of Multilingual Learners.”

What happens when the handful of courses that they took in college don’t apply to a real-life situation? That’s when teachers need the most support, said Michael Henson, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and director of the Brown Center on Education Policy, who wrote in 2017 about the growing need for qualified teachers of English language learners.

“Encourage districts themselves to have a deeper bench that your typical teacher can draw upon in the instances when they do have English learner students in their class, and they find that what they’ve been trained on is not quite cutting it,” Henson said in an interview.

Drawing on her decade-long experience at ELLIS Prep, Principal Norma Vega pointed to all the challenges her new students face. They are often balancing work and school, or life at home may not be stable. One of her students arrived at ELLIS having read only the Islamic holy text, the Quran, in Arabic in his home country.

Facing those challenges can be tough at other schools that don’t have the sort of social and emotional supports at ELLIS, a transfer school that serves older students who are undercredited. And while she thinks the state’s proposal is a move in the right direction, she hopes that policymakers understand how long it takes for this population of students to show signs of success.

“I think we need to embrace the fact that things take time,” Vega said.

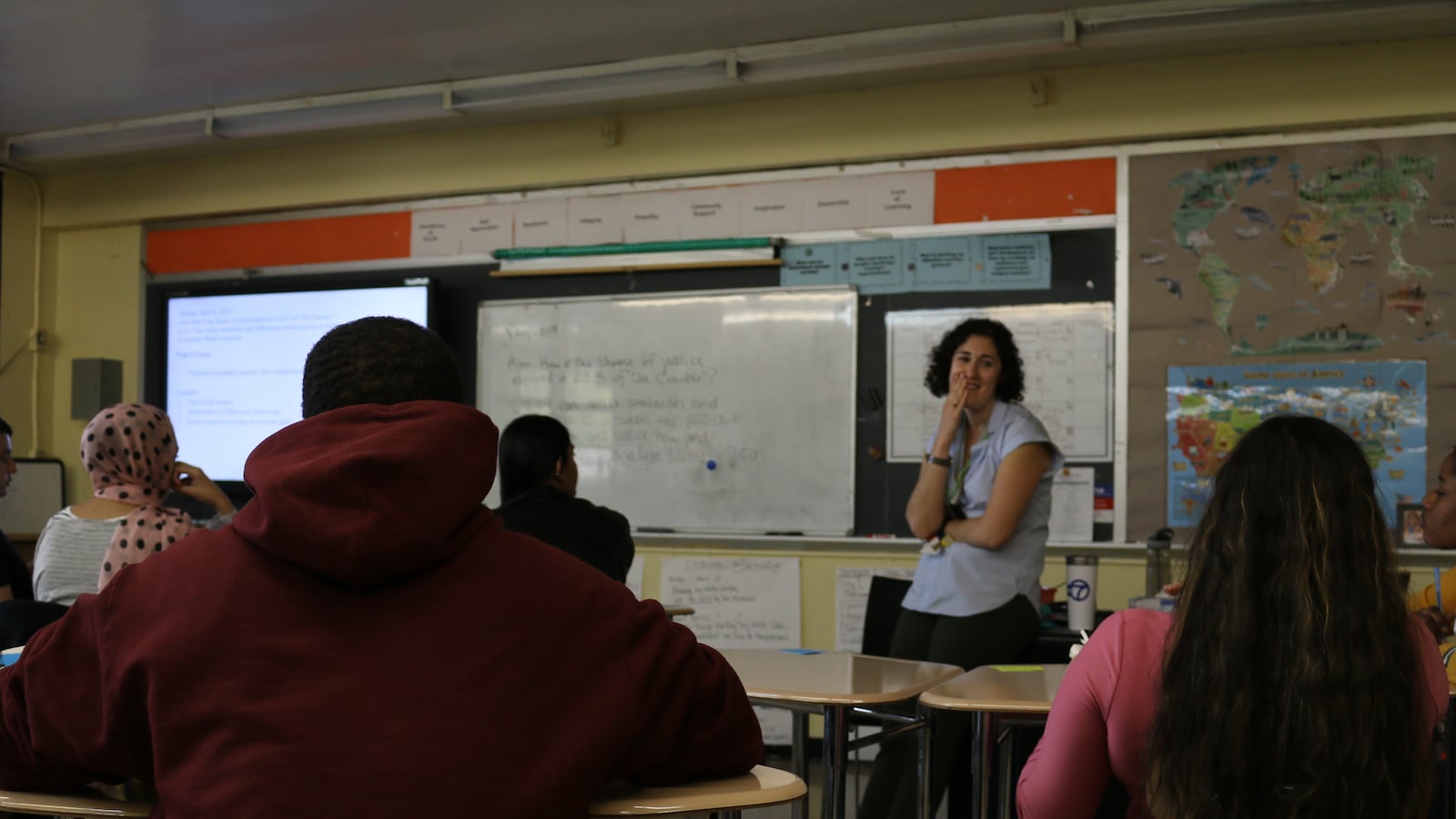

On a recent afternoon, a group of third and fourth-year ELLIS students were sharing opinions in English class about Arthur Miller’s classic play, “The Crucible.” One student was telling the teacher about the play’s depiction of justice when she abruptly stopped. She looked at the teacher, then turned to her classmates: “Como se dice ‘juez’”, she asked (how do you say “judge”)?

The teacher waited and watched the students deliberate. After a few suggestions, the word “judge” was shouted out. “Judge,” the student affirmed, then continued explaining her thought.