On a January afternoon, seven-year-old Jazmiah Vasquez was teaching herself how to make goo out of eye drops, shaving cream, and Elmer’s glue. Based on instructions from a YouTube video, she mixed the ingredients together with a spoon, grinning at the sticky white ooze.

It wasn’t part of a homework assignment or school project. Jazmiah, who is autistic, and struggles with ADHD and behavior issues, has not attended school for nearly a year and a half. The scene playing out in her living room that afternoon was just her latest attempt at staving off boredom.

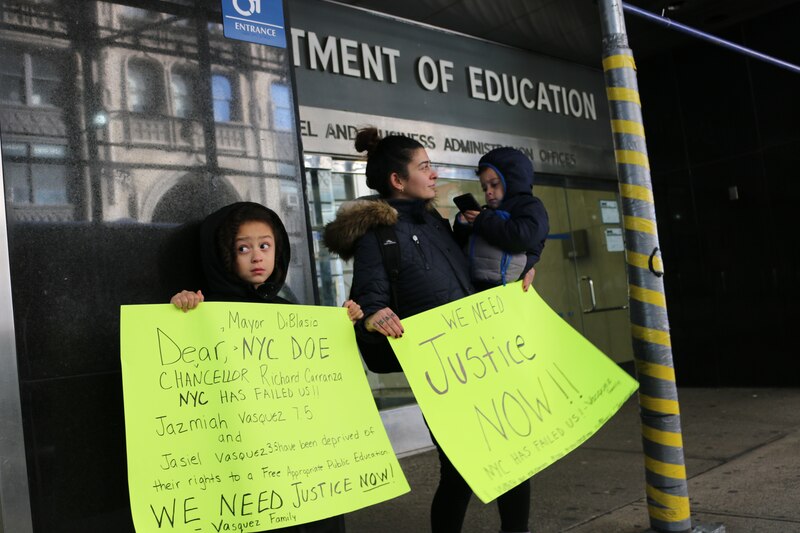

Her mother, Lisa Vasquez, says she is desperate to get her daughter into a school. She routinely emails the education department, has protested outside its Brooklyn offices with her two children in tow, and testified at a February City Council hearing and pleaded with lawmakers to intervene.

A legal ruling, issued last October, faulted the education department for failing to find a school placement for Jazmiah or providing any other appropriate education. But in the six and half months that followed, she was not provided one.

“We’re just existing day to day,” Vasquez said while sitting at her kitchen table on Staten Island earlier this year. “The rope has gone as far as it can go.”

Jazmiah is one of thousands of students with disabilities in New York City who are going without mandated services. According to the city’s own statistics, roughly one-quarter of its 224,000 students with disabilities are not getting all of the help they’re entitled to — or aren’t receiving services at all.

Jazmiah’s case is both complicated and extreme, highlighting some of the failures of the city’s special education system, including the most basic requirement to provide children with schooling. It also highlights the invisible stresses this can create for parents who may not always be best equipped to advocate for their children.

Vasquez, a mother in her mid-20s raising two children with disabilities, lives in public housing and has struggled to continue her education or find work while taking care of her kids. Much of her day is spent seeking a resolution to her daughter’s situation — a campaign that has created friction with officials tasked with placing Jazmiah in a suitable school. According to legal documents, the city education department has argued that Vasquez has at times worked at cross purposes to their efforts to support her daughter educationally.

Just why Jazmiah has languished without a school placement since November 2017 can’t be pinned on a single cause. For years, Vasquez has struggled to navigate the special education bureaucracy and says the city has fallen short providing services ever since Jazmiah started preschool.

According to Vasquez and hundreds of pages of legal records and learning plans, required evaluations were missed or not conducted on time. Services were cancelled or scaled back. And Jazmiah’s underlying learning and behavior issues often went undiagnosed and unaddressed.

Records also show that Vasquez has withdrawn Jazmiah from school on multiple occasions — decisions she says were made because of difficulties securing the right special education environment.

“We are committed to serving every student according to his or her [individualized learning plan], and we have been in frequent communication with this family for several years,” Danielle Filson, an education department spokeswoman, wrote in a statement. “We have made repeated efforts to serve this family and strongly disagree with this description of events, but cannot comment on specific details because of federal privacy laws and ongoing litigation.”

One thing the education department and Vasquez agree on: a private school, funded by the state, is the best option for Jazmiah. But to date, they have struggled to actually enroll her, partly owing to her mix of behavioral challenges and academic promise. Though Jazmiah has an autism diagnosis, her intellectual ability falls within the range of children who are typically placed in general education classrooms.

A solution, however, may now be in sight. According to Elisa Hyman, Vasquez’s lawyer, Jazmiah will have a seat at a school starting in July. But due to ongoing legal issues in her case, it is still not clear how long she will be guaranteed that placement.

“It is no surprise that she is hard to place,” according to a legal order written by John Farago, a hearing officer who has issued rulings on Jazmiah’s case. “Her cognitive potential and mix of learning disability and autism makes it impossible to find an in-district placement,” he added, noting that her behavioral issues also present potentially severe challenges.

In an interview, Farago added that Jazmiah’s case is unusual among the thousands he has presided over.

“Jazmiah still stands out as being more stuck than almost any other kid,” he said.

Challenges from an early age

Vasquez had suspected her daughter might be different from the time she was an infant. Jazmiah seemed fussier than most babies and was slow to reach milestones such as saying her first words or walking. “In my heart I knew something wasn’t right with my child,” Vasquez said.

In preschool, Jazmiah was recommended for speech, occupational, and physical therapy. She also received a recommendation for an individual teacher to help her keep up with her peers in a traditional classroom.

According to Vasquez, those services were spotty — a problem that drew the attention of the Staten Island Advance. The individual special education teacher only materialized several months after the school year had started, according to a complaint filed by her lawyer. Before the school year was out, Vasquez had pulled Jazmiah out of preschool because she felt Jazmiah was “not properly accommodated,” records show.

Vasquez says she has struggled to ensure Jazmiah is getting all of the services she is entitled to and has repeatedly withdrawn her daughter from school in response to situations that she found unsatisfactory.

For kindergarten, Vasquez enrolled Jazmiah at P.S. 46, a traditional public school visible from their living room window at Staten Island’s South Beach Houses. Vasquez said her own education was subpar, and is now raising Jazmiah and her younger brother Jasiel, who is four and also requires special education services, on her own.

Even though Jazmiah was toilet trained, she began wetting herself regularly, Vasquez said. In addition, school officials reported that “Jazmiah would simply get up and walk around during class and was unfocused,” according to a complaint Vasquez and her lawyer filed.

Vasquez traces some of these problems to the re-evaluation process, known as the “turning five” meeting, that every preschool student with a disability is supposed to get. The team recommended removing Jazmiah’s physical therapy services so she wouldn’t miss class time, Vasquez said, even though Jazmiah had trouble with basic motor skills like climbing stairs.

Instead of a one-on-one teacher to help Jazmiah acclimate and manage her behavior, Jazmiah began getting special education in a larger group. Even though Vasquez acknowledges that she was involved in the process, she claims that she did not fully understand the revisions to her daughter’s learning plan, and that she believed Jazmiah should continue to receive one-on-one help. Vasquez also claims she was not given a copy of her daughter’s learning plan.

“I suspected something wasn’t right,” Vasquez said. “I kept sending her because I didn’t know what to do.”

The final straw came that January, though the details of what exactly happened are not entirely clear. Vasquez claims that there was a dispute about whether Jazmiah called another student “gay.” (According to Vasquez it was a misunderstanding, and Jazmiah had difficulty pronouncing the word “gray.”) According to Vasquez’s account, school officials overreacted to the incident, traumatizing Jazmiah. Those at the school and education department officials declined to comment on any specifics of Jazmiah’s story.

The incident solidified Vasquez’s concerns about the ability of P.S. 46 to meet Jazmiah’s needs. Before the end of the year, she withdrew her daughter.

Success Academy

For months, the family scrambled. At one point, Vasquez appeared to push for home instruction — a solution typically designated for students who have significant medical or emotional issues. (Vasquez and her pediatrician say that her daughter’s experience at school had left Jazmiah with extreme anxiety.)

After considering her options that spring, Vasquez ultimately settled on Success Academy Prospect Heights in Brooklyn.

Success has come under fire for its treatment of students with disabilities. State officials recently ruled that the charter network has violated the civil rights of students with disabilities by not providing required support and changing students’ special education services without parental input.

It’s not clear how much Vasquez knew about the network, but she says she was impressed with some of their offerings, including chess, and enrolled Jazmiah for first grade and hoped it would be an improvement on the traditional public school she felt had fallen short.

Jazmiah’s time at Success was brief — she stayed just a few months. Vasquez and Success officials tell very different stories about Jazmiah’s experience there.

Vasquez sent Success an evaluation that detailed Jazmiah’s diagnosis and history and said she was upfront about her daughter’s challenges. And while Success officials say Jazmiah was placed in a class with a mix of students with disabilities and general education students, within a few weeks the school told Vasquez they planned to send Jazmiah back to kindergarten.

The Success principal, Sydney Solomon, wrote in an email to Vasquez at the time that Jazmiah was “performing below grade level in all subject areas,” noting Jazmiah could not count beyond the number 12. (Assessments from the time show Jazmiah was still within the average range in “intellectual function” but showed particular weakness in math.) “Although you may disagree,” the email continued, “this is a decision we made after careful consideration.”

Vasquez pushed back and said she felt like the decision was an attempt to push out her daughter. She said the school repeatedly called her complaining of Jazmiah’s behavioral problems and asked her to pick Jazmiah up early, a challenge given Vasquez had to travel from Staten Island to Brooklyn. She said the school also threatened to call child protective services.

“She had trouble exhibiting appropriate posture during circle time,” Vasquez said, “It wasn’t like she was throwing a desk across the room. They were just looking for a reason to push her out of there.”

Success forcefully denies that characterization. Officials said that even though they moved Jazmiah back a grade, she was acclimating. “Despite a few small incidents, Jazmiah was adapting well to school and did not receive any suspensions or suffer any other serious disciplinary measures,” Success spokeswoman Ann Powell wrote in an email.

A November email from the school’s principal to Vasquez said: “You have have raised weekly concerns that are simply untrue. Jazmiah is happy at school. Her teachers love her.” Powell added that there is no record of the school calling Vasquez to pick up Jazmiah early.

Still, Jazmiah was frequently absent, which raised alarms among school officials. By the end of November, she had accumulated 19 unexcused absences — a pattern that prompted Success to notify child services, Powell said.

In response to questions from Chalkbeat, Success officials provided detailed records of Jazmiah’s time at the charter network, including progress reports, contemporaneous notes from multiple educators and psychologists, and a copy of her learning plan.

Frank LoMonte, an expert on student privacy at the University of Florida, said Success’ disclosure of these records is likely a violation of FERPA, a federal privacy law that protects students’ education records from distribution without permission. “Giving out documents about an individual student’s academic or psychological history is pretty close to the heart of what FERPA was meant to prohibit,” he said.

Success officials defended the disclosure. “It is our position that we are allowed to rebut false claims without violating FERPA when a parent has chosen to go the press but our critics don’t accept that position,” Powell wrote in an email. Success has previously faced criticism for disclosing a student’s records.

Records provided by Success show there were some signs that Jazmiah was making progress, and Powell emphasized the school was “disappointed” she left.

Hyman, Vasquez’s lawyer, disputes that things were going well at Success. She pointed to the fact that Success sent Jazmiah back to kindergarten in response to her struggles with basic reading and math skills.

“It’s outrageous to say she was doing fine under the circumstances,” Hyman said. By December, Jazmiah and Success had parted ways.

‘A wasteland’

If public schools cannot meet a particular student’s needs, district officials can recommend that the child be placed within a special set of private schools that receive public funding. The task of facilitating that decision falls to the district, which is required to hold a meeting with the family, charter school, and district officials.

In November 2017, the attendees at that meeting appeared to agree that none of the city’s traditional district schools or charters were the right fit for Jazmiah, according to a learning plan reviewed by Chalkbeat. That group concluded that Jazmiah’s best option would be to attend a private school, with publicly funded tuition. But such schools are not required to admit students, and finding a spot can be challenging, experts said.

Vasquez said she was told that withdrawing Jazmiah from Success might expedite her placement at a new school, even in the middle of the school year. Success officials said they did not suggest that to her.

But while Jazmiah should now have a placement by July, she has been out of school for nearly a year and a half, putting her on a potentially dangerous trajectory academically, given the large swaths of education she missed during key developmental years.

During that time, Jazmiah has intermittently received some services, including occupational therapy, speech therapy, and tutoring in reading. According to Vasquez, the interim services have not been adequate or comparable to a school experience — a near constant battle.

It is difficult to pinpoint a single reason why Jazmiah has remained out of school for so long. Hyman describes a combination of interlocking factors.

The city has “not built the capacity of community schools to meet the needs of children with autism,” Hyman said. She noted that there is just one state-approved private school on Staten Island, and that it caters to students with more severe needs than Jazmiah.

“Staten Island is a wasteland,” she said, referring to the kind of special education placement Jazmiah needs.

The education department, legal records show, has argued that a key reason for the delay is that Vasquez has thwarted their efforts to place her daughter in a school. But Farago, the independent hearing officer who presided over Jazmiah’s case, disagreed with that assessment.

“The entirety of [the education department’s] case, amounts to an effort to demonstrate, that it has been trying – trying REEALLY HARD! – to effectuate [a school placement] and I am largely convinced that this is the case,” he wrote in his October ruling. “But it is not the law, and not the boundary of the district’s obligation. Rather, the district is legally obligated actually to offer such a placement, not simply to theorize about it or strive to accomplish it.”

And her time out of school has had other unintended consequences. A health department ruling stated that four-year-old Jasiel, Jazmiah’s younger half-brother who also has autism, has not received some special education services because providers claimed Jazmiah’s presence in their home was too disruptive.

“It’s a completely untenable situation to have two kids out of school,” Hyman said.

For its part, the education department says it has made important investments in special education, such as adding $33 million for special education programming in the executive budget as well as 4,300 more special education staff. Officials say they have also increased the number of programs serving bilingual students and students with autism.

Vasquez recognizes her family’s situation could have far-reaching consequences for her kids. “Seven-year-old children who can’t read turn into 17- year-old children who can’t read,” she said.

Much of her day is taken up by efforts to resolve Jazmiah’s situation — a campaign that has put her in daily communications with lawyers, case workers, and city officials. The rest of her time is spent in relative isolation with her children at doctors’ appointments, public assistance offices, and in the living room watching YouTube.

On a January afternoon, Vasquez demonstrated with her children outside an education department building in Brooklyn. They held neon signs that read “We need justice now!!” Eventually, she walked into the lobby and asked to meet with an official working on her case. An education department staff member introduced himself to Vasquez. “We’ve been working on the case every single day,” he said.

Four months later, Vasquez still sends a daily flurry of phone calls, emails, and text messages. Although the city has now found that July placement, Jazmiah, the child at the center of it all, is still waiting.