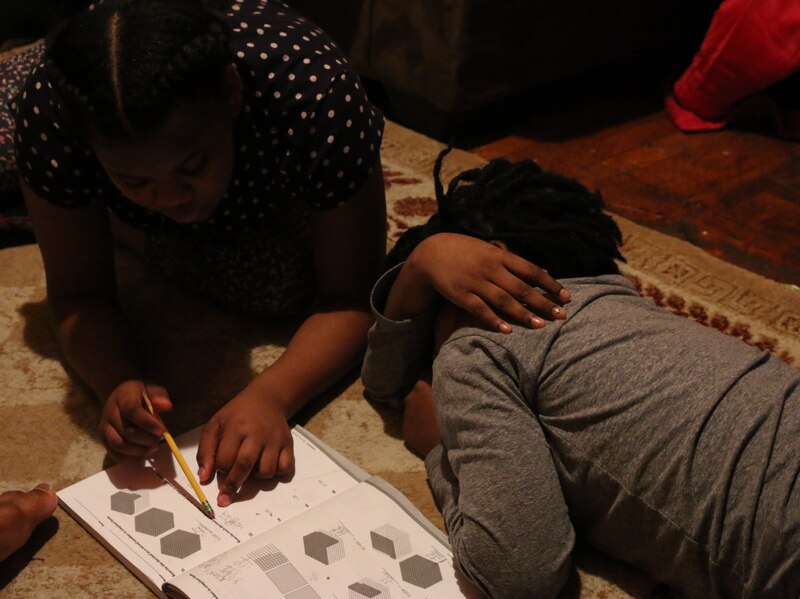

On a Monday evening in February, Niesha Jeffries tried to coax her 10-year-old son, Bishop Ashburn, to finish his math homework in their East Flatbush, Brooklyn, apartment.

A fifth grader at Community Partnership Charter School, Bishop was trying to simplify three pages of fractions but could not concentrate for long and was growing increasingly frustrated and sleepy.

“No, you can’t lay down, sweetheart,” his mother said. “Come on.”

At first glance, the wrangling was no different from countless other battles between parents and children over homework in the New York City school system of 1.1 million students. But as the homework session wore on, the scene grew increasingly desperate. Bishop splashed water on his face as his mother urged him to focus. He moaned and called his mom “mean,” eventually moving from the couch to the floor, where he could barely sit up. He alternated between curling in a fetal position and holding his head in his hands, trying but unable to stay on task for more than a few minutes at a time.

Bishop’s struggle, according to Jeffries and specialists who have examined him, is likely the result of permanent brain damage caused by his early exposure to lead, affecting his ability to learn.

In January, the city invigorated its efforts to prevent lead exposure in children with the new program, LeadFreeNYC, after scathing reports about the prevalence of lead in New York City public housing. The $50 million program aims to stamp out childhood lead exposure by 2029 and would mandate more inspections in private dwellings while connecting affected children with nurses to coordinate follow-up care. And the City Council also passed a series of bills in March aimed at strengthening its lead-related laws, including increasing public awareness. Lead exposure appears to be sharply declining in the city for children under the age of 18, to just 4,717 cases with concerning levels as of 2018 from a high of 17,054 in 2010.

But the city’s new initiatives do nothing to address lead’s lasting effects on thousands of city children like Bishop. When Bishop was first tested for lead in 2010, he was one of almost 14,000 children under the age of 6 that year with worrying levels in their blood, according to the most recent city data. And the actual numbers could be higher — roughly half of New York’s Medicaid-enrolled children were not tested for lead in 2014, a Reuters investigation found. Many of those children are likely now navigating a school system not equipped, advocates argue, to contend with the unique challenges lead poisoning poses for students, parents, and schools.

The education department performs an evaluation that includes a cognitive test and considers a student’s social history to recommend special education programs and related services to address the needs of students with disabilities, a spokeswoman for the department said. But those special plans may fall short for lead-poisoned students because the testing for disabilities isn’t comprehensive and detailed enough to identify and then address the permanent brain injuries lead exposure can cause and their effects on development, some psychologists and advocates have argued.

Bishop receives speech and occupational therapy as part of his special education services but still reads grades below where he should, struggling to keep up in multiple subjects. But following a more comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation, two specialists determined that his needs are greater than his family or school previously recognized — and that his current school can no longer help him. After hearing about those specialists’ findings, the guidance counselor at Bishop’s school agrees with this prognosis.

“We need to find somewhere where he can get the academic remediation he needs,” said Jayson Brown, a social worker at Community Partnership Charter School, who has known and worked with Bishop since kindergarten.

Cases like Bishop’s are also why some advocates have asked the City Council to create a law that would automatically entitle lead-exposed children to the same comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation that Bishop recently had, which is the type of testing now legally mandated in Flint, Michigan, following its lead crisis.

Vicki Sudhalter, a former New York City teacher who performs comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations locally and in places such as Flint, was one of the specialists who examined Bishop and said there is no time to waste.

“We will lose Bishop if we don’t provide him with the accommodations he needs,” she said, “and a better self image of himself to at least put in the effort to try.”

Paint chips and an incomplete recognition of lead’s perils

Jeffries, a conductor with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, first became concerned about Bishop’s development in 2010, when she, her four children, and her mother were living in a first floor rental home in Prospect Lefferts Gardens in Brooklyn.

As Bishop approached his second birthday, Jeffries noticed that he still wasn’t talking, a milestone his older sisters had reached at that age.

As Bishop wailed, a technician drew his blood during a routine physical on Nov. 8, 2010, and tested it for lead exposure. State law requires such testing for all 1- and 2-year-olds. Health records show Bishop’s blood had nearly four times the level at which the Centers for Disease Control recommends public health agencies get involved.

“When the lead came, that’s when everything came into perspective,” Jeffries said. “The doctor was telling me that’s probably why he’s delayed in his speech.”

Because of a city law governing cases of heavy lead exposure in children, city officials were notified of Bishop’s test results, and a city inspector found lead in 54 areas of the Jeffries’ home, according to city records obtained by Chalkbeat. Noting the peeling and chipped paint, the agency labeled the home as hazardous for young children, who are most vulnerable to lead exposure because they may crawl on the ground and eat the chips or stick fingers covered in paint dust in their mouths — a potential peril Jeffries hadn’t fully recognized before.

Documents show the city offered Jeffries a lead-safe home but that she declined, something Jeffries doesn’t recall, insisting she would have welcomed another place to live. Instead, she said she kept the children isolated in one bedroom where lead wasn’t detected and moved them to the home of her partner’s mother while the lead was abated months later.

According to inspection records, the city had trouble tracking down the landlord, who didn’t respond to multiple city orders to fix the lead violations. (The landlord, who could not be reached and whose lawyer declined to comment, would later tell inspectors that officials had been trying her at the wrong address.) Jeffries has an active lawsuit against the property owner.

Responsibility for addressing the lead next fell to the city under its lead laws. The city was required to file orders for cleanup, then fix the matter on its own if needed within 34 days of receiving notice of Bishop’s test results. In fact, the entire process took four months. City health officials blame the delay on difficulties reaching the landlord and setting up appointments with Jeffries.

“The important thing is that obstacle doesn’t stop us from achieving the results, which is to get the damaged paint repaired,” said Corinne Schiff, deputy commissioner of environmental health, in a statement.

In the meantime, Jeffries said she was following instructions from Bishop’s doctor, who advised her to keep Bishop from the lead-exposed rooms and to feed him more vegetables and iron. Research shows a focus on nutrition and coordinated services can boost student learning. The city also monitored Bishop’s lead level until it went down to less worrisome levels.

In addition, Jeffries signed Bishop up for a city early intervention program, which pairs families with coordinators who help children at risk of developmental delays. She recalls a coordinator coming once a week and focusing on improving Bishop’s speech development. It was challenging at first, but Jeffries began to see the difference.

“When he started talking more, I was like, ‘Oh my God, OK,’ maybe he’s not going to have a delay — maybe this and maybe that,” Jeffries said. “I felt like it was progress.”

By early April, the lead abatement was finally finished, after the city hired a company to complete the work, inspection records show. (Jeffries filed a separate lawsuit against the company, alleging it didn’t properly clean up the lead, even though the company submitted paperwork that showed otherwise.)

That July, Jeffries’ attorney, Reuven Frankel, hired a consultant to check the apartment for remaining lead; they still found traces of it in the home. In the months after his first blood test, Bishop’s lead level had dropped to 5 micrograms per deciliter, right at the cutoff where intervention isn’t typically seen as necessary. But by August 2011, it had risen again to 9 micrograms per deciliter.

That same month, now 10 months after Bishop’s lead test, Jeffries and her family moved out of the house for good and into their current East Flatbush apartment. But tackling school would be Bishop’s next big battle.

“Ma, I can’t do it” — interventions but mounting difficulties in school

Three years later, Bishop entered kindergarten at Community Partnership Charter School in Brooklyn, after getting special education services in preschool. He was assessed and deemed eligible for speech therapy (occupational therapy would come later). The motherly fear that had been gnawing at Jeffries was starting to subside. Her son’s lead ordeal appeared to be over — until second grade, when he began to fall further below benchmarks for grade-level reading and was struggling with speaking aloud. Jeffries recalls Bishop’s classmates teasing him for stuttering, and the school calling twice to report that Bishop had thrown objects because he was frustrated with his teachers. He was often not doing classwork at all, Jeffries said.

By third and fourth grades, homework was becoming an obstacle as well. Sometimes Jeffries watched him work, and within minutes he would zone out.

“He’ll be like, ‘But I need help,’ and I’ll try to help,” Jeffries said. “And then sometimes, he’ll be like, ‘You know ma, I can’t do it.’”

Brown, the social worker at Bishop’s school, said he is well-liked by classmates. He enjoys gym class — and loves football — and science because of the experiments. Making a light bulb light up is a favorite activity, Bishop says. But he also faces severe academic impediments and struggles to express his feelings or what he needs.

“If I think about the lack of growth, I think that’s where it’s the most concerning,” Brown said. “We’ve seen the same issues presented the same way over the course of first through fifth grades — what is that, five years?”

But Bishop’s individual education program for most of this school year, which is largely based on special education evaluations from third and fourth grade, mentions lead only once and ties it solely to his inability to focus. He recently received a new program that Chalkbeat has been unable to review, but his mother has reviewed the document and described it as largely unchanged, beyond prescribing more time for test taking.

The “cardinal features” of lead exposure

Bishop was exposed to lead when his central nervous system was particularly vulnerable, said a November 2018 report by Dr. Karen Hopkins, a specialist in pediatric and behavioral development at New York University’s Langone Health Center. Bishop’s difficulties, she found, were with language-based learning such as reading, which a lot of school work is based on.

Hopkins, who developed the report at the request of Jeffries’ attorney, said she believes “with a reasonable degree of medical certainty” that nothing in Bishop’s medical history besides the lead could have caused his neurodevelopmental weaknesses, and that the “full extent of the damage” will become clearer as classwork gets harder.

Bishop’s attendance has also been an issue, which the school flagged when they almost held him back last year, Brown, the social worker, said. This year, he has missed 21 days of school as of May 1. Jeffries, who is a single mom, said a number of factors has contributed to his poor attendance, including court proceedings and other health issues, such as Bishop’s asthma.

Hopkins noted that Bishop’s current school program can’t meet his needs, an assessment his school counselor validated.

“If this is what’s causing the deficits in his learning, then this really this isn’t the right place because we can’t give him the one-to-one services that he needs,” Brown said.

The night of the homework wrangle, Bishop was visibly fed up and couldn’t maintain focus. “I don’t like nothing,” he said when asked about his favorite part of school. “I don’t like reading; I don’t like math.”

It can be hard to separate exactly where the impact of lead exposure ends and other learning difficulties may begin. Lead’s effects can also take different forms in different children. But irritability and the inability to pay attention are “cardinal features” of excess lead exposure, said David Bellinger, a professor of neurology and psychology at Harvard Medical School who has studied the effects lead has on young nervous systems. Children become unable to sit in their seat or follow directions and are disorganized, he explained — which could be the case for thousands of other children who have been exposed to lead in New York City.

Bellinger hasn’t evaluated Bishop but said, in general, a child with his level of lead exposure “would have a somewhat reduced IQ score and would be expected to struggle with academic progression and difficulty reading and doing math.”

Jeffries has seen little improvement from Bishop this school year.

“The fingerprint of a brain injury” — a new approach, pioneered in Flint, Michigan

Cases like Bishop’s are familiar in Flint, Michigan, where a group of doctors discovered in 2015 that the city’s municipal water supply was contaminated with high levels of lead. Now, some child advocates in New York City are pushing for a law that follows Flint’s example for identifying students who need more help in school.

In 2016, attorneys representing Flint students sued the Michigan Department of Education, Flint Community Schools, and the system’s parent agency, the Genesee Intermediate School District, alleging students were not properly being identified and offered appropriate special education services. The attorneys hired Ted Lidsky, a neuroscientist who specializes in behavioral neuropsychology, to evaluate some of the children involved in the case. He concluded that the best assessment for Flint’s children was what other doctors and psychologists recommend — a comprehensive neuropsychological exam that gives a deeper picture of what’s going on inside the brain and a better idea of what children need to make it through school.

“Whenever you are attempting to make inferences about the integrity of the brain, it should [be] through a neuropsychological evaluation conducted by an expert (i.e. a neuropsychologist),” wrote Douglas Ris, a clinical neuropsychologist at Texas Children’s Hospital and a psychology professor at the Baylor College of Medicine, in an email. “A psychologist in the school is not likely to have undergone such specialty training.”

Brown, Bishop’s school counselor, concurred.

Some research also backs up this approach. In a 2015 CDC paper, a panel of experts found that “all children” with high lead levels should be screened “using neuropsychological evaluation tools that provide a complete assessment to identify the complex subsystems in the brain that work differently when affected by lead.”

In a partial settlement reached last April in the Flint families’ lawsuit, the Michigan Department of Education agreed to spend about $4 million to create the Neurodevelopmental Center for Excellence, or NCE, where Flint children can get screened and receive comprehensive evaluations. More than a thousand children have been referred to the center to date.

Children receive an initial screening to see if they need more comprehensive evaluations, which would take place over several hours. The final report from the longer evaluation includes the child’s social history and behavioral observations and results from a battery of memory, language, and sensory-motor-skills tests. This data then helps a neuropsychologist at the Center recommend additional resources children might need in the classroom to help them learn despite brain damage, such as more more one-on-one time with an instructor.

“If you think of a road, and it’s blocked off, and you can’t get through, your job is to try to find a detour,” said Katherine Burrell, a clinical psychologist and the NCE’s associate director of assessment services.

In New York City, children who are assessed for special education services receive a specific evaluation that focuses on IQ, academic strengths and weaknesses, and interviews with the student. The city’s process for determining such services also considers a student’s social history, developmental milestones, family history, health and a recent physical exam, and environmental factors.

But none of that does the work of a neuropsychological comprehensive evaluation, Lidsky said, which involves evaluating “dozens and dozens” of brain functions and can pinpoint specific issues, for example, with learning and memory.

“It’s focused testing really used for identifying the fingerprint of a brain injury,” Lidsky said.

Jeffries’ attorney contacted Sudhalter, the former New York City schools teacher who performs these types of comprehensive evaluations (including in Flint), to conduct a neuropsychological evaluation of Bishop. It took place in late March.

Sudhalter found that Bishop has strong memory skills but scored in the lowest percentiles for verbal comprehension, fine motor skills, controlling impulses, and processing information — he can remember what his teacher asked him to do, for example, but has trouble carrying out the assignment.

That variability in strengths, Sudhalter said, is a typical sign of brain damage. But it’s also very confusing for a child who doesn’t understand why he can do one thing but not another, she added. And it can also be confusing to teachers. “The first thing they would say is, ‘You’re not trying,’” Sudhalter noted.

One education program for Bishop notes his specific academic hurdles but also describes his refusing to follow the rules and becoming “unmotivated quickly,” and often showing “disinterest and boredom” during reading assignments. Sudhalter suggests that teachers and classmates may not understand the full nature of Bishop’s struggles — and if they did, they might approach his classroom instruction differently, even if all the resources weren’t there to help him.

Sudhalter was struck by just how much Bishop’s self-esteem has apparently suffered. She noted that without constant encouragement, Bishop struggled to do some of the activities required by the evaluation. At one point, he ran out of the room crying because he didn’t believe he could complete a task, Sudhalter wrote. Bishop’s counselor, too, has noticed the boy hiding his face behind his long hair when he feels embarrassed, instead of reaching out for support.

“I worry that being here, when he sees other people being successful …he’s going to get more and more reserved and be less likely to ask for help, and his problems are just going to start to fester,” Brown said.

Sudhalter concluded that Bishop needs more one-on-one help in a small classroom setting, at a private school for students with disabilities, and more frequent occupational and speech therapy. But he also needs psychological therapy, she said, to address his withered self-esteem and should continue to receive an unlimited amount of time to take tests.

Sudhalter stopped short, however, of criticizing Bishop’s current school. She noted that public schools are willing to help but “do not have the personnel nor the training to help Bishop learn.” But she noted that if things don’t change, it will be nearly impossible for him to graduate.

Parents in New York City can request a neuropsychological assessment and ask the education department to pay for it, which at a private practice can cost between $3,500 to $5,000. But parents don’t typically know that option exists, said Frankel, Jeffries attorney, who has worked with parents of lead-exposed children. And in a system already struggling to meet the needs of its existing special education population, it’s uncertain whether there is really capacity to help such students.

Over the past two years, Frankel and a group of advocates – including the Children’s Defense Fund and the Northern Manhattan Improvement Corporation – have quietly floated a change in city law requiring that when a child has been exposed to lead and the family suspects a learning disability, the Committee on Special Education must immediately connect that child to comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations.

Frankel and Lidsky argue that setting up such a system might be easier than it sounds. Current school psychologists could administer the more thorough exam and a neuropsychologist could then be tapped to decode the results and provide recommendations.

“It would happen as a matter of routine,” said Frankel, and this way, schools would ultimately know what a child’s deficits really are.

The City Council is taking the draft into consideration, “as we do with all the feedback we receive from advocates,” wrote Breanna Mulligan, a spokesperson for the council, in an email.

Asked if the city is considering introducing such evaluations, a City Hall spokeswoman pointed to what the health department already does: contact the family, offer early intervention services before kids enter school, and monitor blood lead levels until they go down. “This is only just the beginning of our LeadFreeNYC Plan, and we will continue to look for ways to keep our kids safe,” she said.

Despite those services, however, Bishop and his mother continue to struggle, just as other New York City families whose children are experiencing the lasting effects of lead exposure might be. Sudhalter has suggested Bishop should attend a private state-approved school for students with disabilities, but this requires a recommendation from the committee on special education. It’s unclear whether Jeffries would pursue that option, and she’s hesitant to move him from a mainstream environment.

The night of the homework wrangle, Jeffries became frustrated by the son she also wants to help. “You’re gonna repeat the fifth grade,” she said. “You’re not going to like it. You have to do your homework.”

Bishop didn’t respond.

Jeffries then picked up her son, set him on her lap and wrapped him in her arms. She asked him to close his eyes and clear his mind — a method she picked up from her own therapy sessions. Both of their eyelids closed, Bishop leaned into his mother’s shoulder. About a minute later, they erupted in laughter, a moment of levity amid the enormous challenges they — and perhaps thousands of other families — still face.