This story was originally published on June17 by THE CITY in collaboration with Measure of America. Léalo en español..

Gabriela Ureña began worrying about her son, Lucas, when he was 15 months old.

During a check-up, Lucas’ pediatrician grew concerned, too. The Bronx boy could only sound out three words. He couldn’t imitate names of familiar objects or gesture to request food, records show.

The physician sent a two-page referral to the city’s Early Intervention Program offices in Lower Manhattan. This federal program mandates that local governments provide necessary therapies and services to children 3 and under with severe delays or disabilities.

If a program coordinator determines a child’s speech, gait or social skills are significantly delayed, the toddler becomes eligible for free services. Within 45 days, specialists must design an individualized care plan with up to 40 hours a week of therapies.

It took twice as long for a plan to come together for Lucas, who has autism. And his 25 hours a week of therapy quickly decreased to five when the two behavioral therapists couldn’t coordinate their schedules, and then one stopped coming to the family’s home on the northern edge of The Bronx.

“I called and called, and they never sent somebody new,” Ureña said, her raspy voice jumping an octave higher. “It’s just a mess.”

The Early Intervention system that provides a lifeline to children with developmental delays and disabilities is facing its own struggle to thrive — suffering from a shortage of providers and geographic gaps in services that are falling hardest on young black and Latino New Yorkers.

And accessing this care has become increasingly onerous for families — nowhere more so than in The Bronx. An analysis by Measure of America and THE CITY of records from the state and city health departments reveals:

• Last year, about one in five Early Intervention agencies got a failing grade from the city Department of Health for service coordination for kids, with almost as many providers judged “marginal,” a number that’s been rising, agency records show.

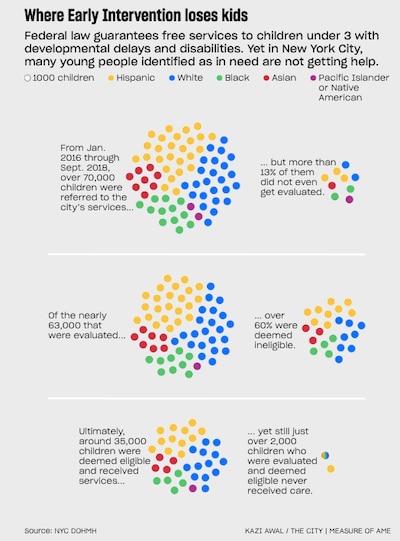

• Between January 2016 and September 2018, one in five black children and nearly one in seven Latino children referred to Early Intervention never received evaluations to determine whether they were eligible for services, according to reports from the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Fewer than one in ten white children referred didn’t receive evaluations.

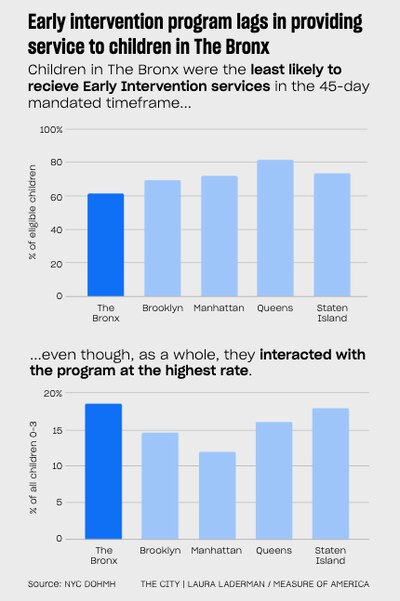

• In that same period, three out of five Bronx children deemed in need of services actually received them in the legally required timeframe — fewer than in any other borough, indicate records obtained by Measure of America/THE CITY from the state’s Department of Health.

In interviews, exasperated parents told of a system that has failed to meet their children’s needs: Therapists arrive late or miss appointments altogether. Non-English speakers get placed on waiting lists because too few therapists speak their languages. Program coordinators say they can’t arrange for certain services because of a lack of providers in a child’s zip code.

“That is patently unfair,” said Kaiesha Scarbrough, who was told no respite care workers were available to come to her East Bronx home to help her care for her partially paralyzed daughter.

“We are one city and we don’t have unified access or unified services,” said Scarbrough, a lawyer for a city civil service union. “The families that need this the most are disadvantaged because of the zip code they live in. That is a type of zip code Jim Crow.”

The city budgeted $218.8 million for the Early Intervention Program this year, with more than half of that coming from state funds. Now a scrambled system is about to lose longtime anchors — five borough centers that help direct families to Early Intervention and other early-childhood services. Those centers will close June 30, on the order of state officials.

A ‘Disheartening’ System

The stakes are high for in a city where more than 71,000 referrals were submitted to the program on behalf of children between 2016 and September 2018.

Nearly 9,500 of those children were not evaluated, according to data the city Department of Health presented to the Early Intervention Council, an advisory group of advocates, parents, academics and service providers.

“That is really disheartening, to say the least,” said Chris Treiber, who used to chair the council and remains on its board as a representative of the Interagency Council of Developmental Disability Agencies. “When you have children who have been identified at such a young age to receive care, and they can’t access it, that is a failure.”

Congress added the Early Intervention Program to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in 1986 in recognition of “an urgent and substantial need” to bolster the development of children with delays and assist their families. The goal is to “reduce the educational costs to our society” by decreasing reliance on pricier government services later in life.

“If you intervene early and give kids experiences that will strengthen the brain circuits when they are forming, you can form pathways in the brain that will be usable for children throughout their lives,” said Judy Cameron, a psychiatrist who directs a neuroscience lab that examines brain development at the University of Pittsburgh.

Lucas got further with Early Intervention than many kids, some of whom never get to an evaluation — and whose caregivers never even hear from the service coordinators paid to make sure children connect with the help they need. The state Department of Health reimburses agencies just $18 an hour for the coordinators’ services.

Katie Keown, a pediatrician with Columbia University who works at a clinic in West Harlem, says her office sends about two or three referrals a week on behalf of patients. Program staff are then supposed to forward the referral to one of the Health Department’s contracted private agencies, so that a service coordinator can set up an evaluation.

Yet a couple of times a month, either Keown or her staff hear from a patient who was never contacted by a coordinator. One pediatrician observed this often happens with referrals submitted on behalf of children who are older than two-and-a-half and speak Spanish.

Lidiya Lednyak, senior director of quality assurance and policy for Early Intervention at the city Department of Health, said she is not aware of parents or caregivers failing to hear back from the program but is familiar with families choosing not to move forward with the program.

“If pediatricians are seeing that there are any problems or barriers in getting an early intervention evaluation, we need to know about that immediately and they need to contact us,” she said.

Even when caregivers do connect with a service coordinator, they may struggle to find the time and place to make an appointment. Households where parents work multiple jobs, live in crowded home or are moving constantly are at a disadvantage. A lack of trust in government systems, particularly acute for undocumented caregivers, also discourages participation.

Come June 30, each borough will be losing its Early Childhood Direction Center, where for the last four decades experts have been helping families navigate day care, preschool and other services and connect to resources, including evaluations.

The state Department of Education announced last year that it would be terminating contracts with the centers. While the state is now soliciting new groups to help families navigate options, and a state law requires the centers to identify children to refer to the program, Early Intervention is not named in connection with deliverables. “It’s really not clear who is going to fill that void,” said Treiber.

Concerns About Stigma

Early Intervention officials at the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene say they are well aware of the barriers children face in accessing the free help they’re entitled to.

Staff have launched radio campaigns to encourage enrollment and created toolkits for people referring children to the program, among other outreach efforts. “Really, the effort is to address the stigma … with developmental delays and disabilities,” said Lednyak.

The department’s Center for Health Equity analyzed Early Intervention data and recognized the disparities among the thousands of children not receiving evaluations. “We started to ask questions about why black children were utilizing free, eligible services at a lower rate,” Aletha Maybank, the former director of the center, said in testimony last year to the City Council committee on health.

A central reason, they concluded, were fears surrounding how a government agency labeling a child as impaired might limit opportunities later in life. In reality, the program is prohibited from passing along information about the child or family to any other government agency unless the parent requests it or approves.

“The program is now building demand by getting out the news about these free services, and educating providers in prioritized neighborhoods,” Maybank testified. At an Early Intervention Council meeting last April, a Health Department employee discussed projects taking place in southwest Queens and Jamaica, according to meeting minutes.

And yet the rates of black and Latino children who are not getting help after being identified as potentially in need remain stubbornly high. “In communities where it is more difficult to get to, where there is less access to public transportation, where therapists might not be able to access so quickly, those are the ones that are not receiving all the services they should be,” said Treiber.

Nowhere to Turn in The Bronx

Kaiesha Scarbrough can’t shake the response she got when she sought a day care center in the East Bronx that could accommodate her daughter, who’s now about three and a half and has an autoimmune disease that left one of her legs paralyzed and the other weak.

Their Early Intervention coordinator sent Scarbrough an email listing locations, and told her to contact the schools, even though the city’s program manual says making these arrangements is the coordinator’s responsibility. None of the 15 centers in the area could accommodate her daughter. So Scarbrough requested respite care.

The service coordinator said she couldn’t find any service providers that delivered that type of care in Scarbrough’s zip code.

“If you lived in Manhattan or even Brooklyn, I could get you more,” she remembers the coordinator telling her.

The manager who oversaw the service coordinator for Scarbrough’s daughter said that while confidentiality prevented her from talking about the case, it’s common to come up empty in seeking therapists to go to some neighborhoods.

One reason, providers say, is paltry state pay for therapists, reducing the incentive to travel. A 5% bump in this year’s state budget isn’t changing that, they say.

“If your offices are in midtown, you might have to travel an hour to get to the home, and then if the person isn’t there and you don’t provide the service, you’ve lost out on billable hours,” said Romina Borsani, who owns and oversees an early intervention program and used to work for the city’s early intervention team.

Concerns about safety can also come into play. Borsani said she once called in for re-assignment because she was worried about her safety. Eight providers interviewed for the story say this hasn’t changed. “There are certain neighborhoods where therapists just don’t want to go,” Treiber said.

The pressures have taken their toll. After the state cut funding in 2010 and 2011, dozens of providers shuttered across the state and city. Public Health Solutions, which had been operating since 1994 and administered the city’s largest service coordination program, closed in June 2017 after running up a deficit exceeding $1 million, said Lisa David, who was the organization’s president and CEO.

As she struggled to retain staff, the timeliness of care suffered, she said — falling heavily on children who could most benefit. “The sort of barriers low-income and immigrant people face across all the services, that’s a structural problem that we have,” said David.

The Department of Health notes it has increased the number of Early Intervention providers it contracts with, from 88 in 2013 to 165 this year.

Providers said that doesn’t represent an increase in capacity to serve children. In 2013, the state started authorizing individual therapists to treat children on their own, instead of having to be affiliated with an agency. “Just because there is an increase in providers does not translate into additional services or guaranteed services in all locations across the five boroughs of New York City,” Treiber said.

The Early Intervention Council tried a few years ago to establish a subcommittee to examine why service lags so severely in The Bronx, but the effort fizzled after a few sessions.

The city has been in talks with the state to mandate that service providers cover certain geographic areas, Lednyak said. Another idea is creating catchment areas to ensure each neighborhood gets equal access — a goal that City Councilmember Daniel Dromm (D-Queens) hopes to further with a bill that would require the city Department of Health to publish key Early Intervention data annually, broken down by zip code.

After Measure of America/THE CITY shared Scarbrough’s experience with Lednyak, she said she was surprised and planned to reach out to Achieve Beyond, the agency that employed the coordinator, to ensure staff are aware that it is their responsibility to facilitate this care to all families, no matter their zip code.

The coordinator’s manager, though, told Measure of America/THE CITY they are unable to find providers who have both the time and willingness to serve the region.

Lednyak urged anyone enduring similar situations to call the bureau’s Office of Consumer Affairs.

Lucas Still Needs Help

During the two months when Lucas was getting full therapy services, his mother noticed improvements in his speech and behavior almost immediately. He began gesturing to food he wanted. He spoke more.

For the moments when Lucas experienced fear, moments that could quickly turn into tantrums, the behavioral therapist taught Ureña techniques she still uses today to help calm him.

Meanwhile, Lucas has aged out of Early Intervention — a door that closes when kids turn 3.

Now 4 and a half, Lucas rarely speaks. Ureña thinks about how frustrating it must be to be hungry but unable to say so, or be unable to express if something hurts.

On a recent Saturday, Lucas wailed when Ureña dropped him off at a new day care center she had spent months trying to get him into. Two days later, she received an email saying they were “unable to manage him,” and would help her look for other arrangements.

As Ureña read the email, she wondered how life would be different if Lucas had the tools to communicate like others his age.

“I feel like if he would have had all the services, and they would have helped him the way they were supposed to, he would be more advanced right now, and he would be talking more than he is,” she said.

Maya Miller is a data and health journalist with Measure of America, a program of the Social Science Research Council.

This story was originally published by THE CITY, an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.