Months after top officials said they were ending Mayor Bill de Blasio’s controversial, $773 million Renewal school turnaround program, school leaders, union officials, and even the people responsible for supporting schools on the ground are still in the dark about what to expect next.

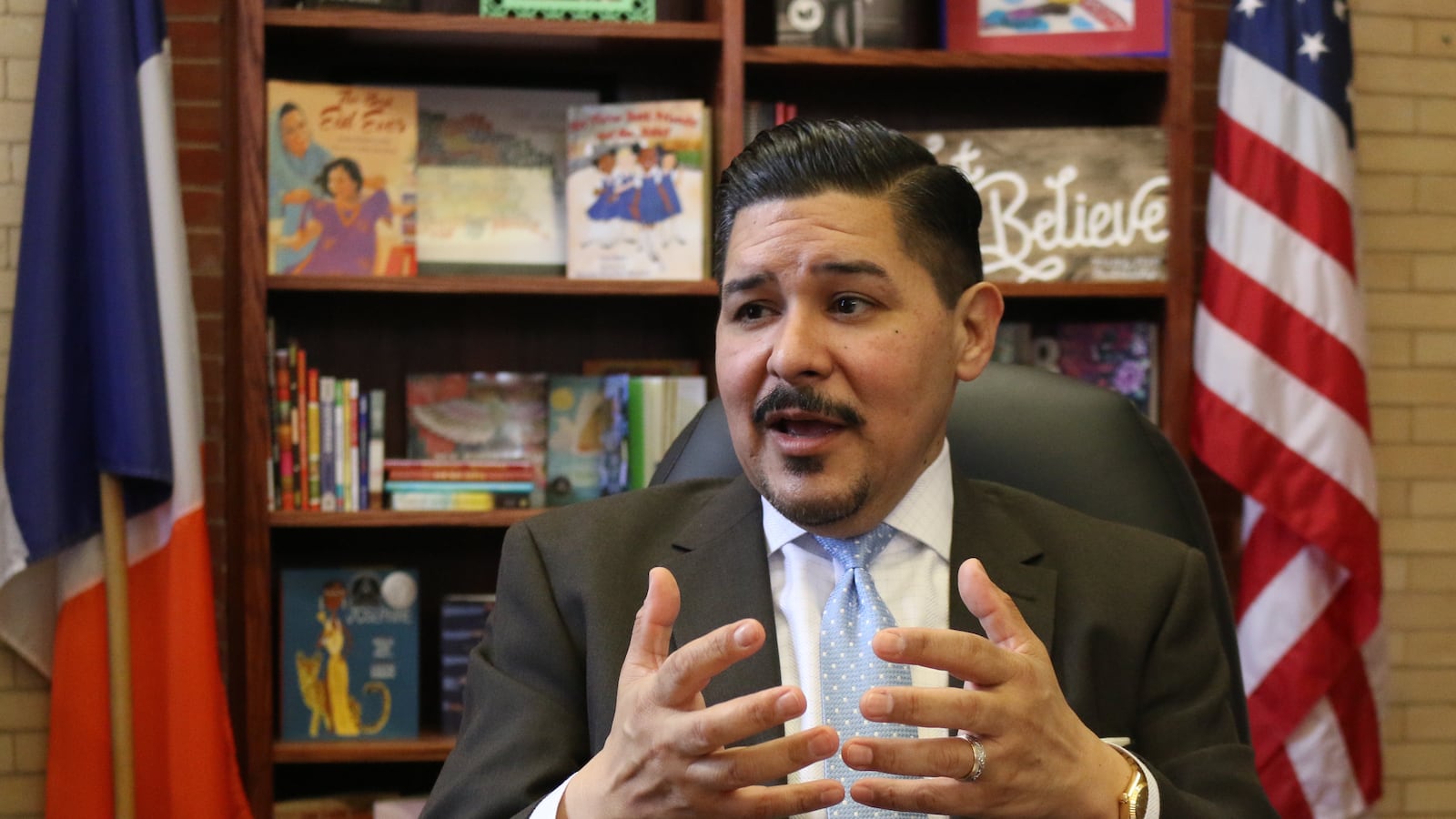

In February, de Blasio and schools Chancellor Richard Carranza promised a new framework for school improvement, one that doesn’t focus only on the lowest-performing schools and would not hinge on a rigid set of interventions.

But interviews with principals across the city, both inside and out of the city’s now-shuttered Renewal program, suggest schools lack precise details about what type of support they will receive, creating uncertainty for the coming school year. And the senior official responsible for overseeing “continuous school improvement” abruptly resigned this month, potentially complicating the education department’s efforts.

“We’ve gotten no instruction or guidance on what will be provided,” said one administrator at a former Renewal school in Brooklyn, who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity because this individual wasn’t authorized to talk to the press. “There’s just a general lack of information about what the borough offices are doing, how they’re structured, how they’re staffed, and what they’re doing to support schools.”

Carranza’s new improvement effort, called “Comprehensive School Support,” is based on the idea that every school in the system should receive different types of help based on their individual needs. That is a big departure from Renewal, which was designed to rapidly improve just 94 of the city’s lowest-performing schools with a fixed menu of interventions, such as partnerships with social service organizations, changes to curriculum, longer school days, and access to leadership coaches.

After four years, more than three-quarters of a billion dollars, and limited evidence of meaningful improvements at most schools, officials announced they would phase out Renewal at the end of last school year. They promised schools wouldn’t lose many key pieces of the program — such as nonprofit partnerships that offer everything from dental clinics to mental health counseling — or funding increases they received. But the education department ultimately rolled back other features, such as lengthening the school day by an hour.

The shift in philosophies — from a defined set of interventions to more fluid support — has left some principals feeling a sense of limbo. One Renewal school leader said it is still unclear whether schools will receive coaches, who train teacher leaders how to help their peers improve instruction and how to use student performance data to make tweaks to their teaching practices over time.

“We’ve been waiting to find out whether there’s going to be any coaching support through the borough offices,” the administrator said, making it difficult to know how to budget for the coming school year, since the school would have to find a way to pay for coaches once provided through Renewal.

But some leaders welcomed aspects of the change. Ronald Saltz, who runs Replications, a non-profit that has worked in a handful of Renewal schools, said he is optimistic that school communities will have flexibility to participate in decisions about what they need.

“That sense of, ‘build the collective from the school-level up’ rather than ‘do it my way from the district level down’ is a very different feeling,” he said. “The lines of communication feel clearer and more coherent now than they did at the beginning of the Renewal work.”

Ben Honoroff, the principal of Brooklyn’s M.S. 50, said he was glad the city is keeping many elements of the Renewal program even as it officially ends. The school will continue its partnership with a nonprofit organization that helps with everything from after-school activities to home visits where staff distribute information about the high school admissions process. It will also continue to receive the funding boost it got through the initiative.

“I’ve always been a big supporter of Renewal [and the] support that we got,” Honoroff said.

There are other areas, however, where Honoroff has been less enthusiastic about the city’s strategy. Along with every other Renewal school, he extended the school day by an hour, time filled with enrichment activities including his school’s hugely successful debate program, volleyball, and a class dissecting biases embedded in Disney movies.

Citing budget pressures, city officials cut funding for the extended school days, which has infuriated the principal’s union and has left school leaders like Honoroff scrambling to figure out how to fill the gap out of their own budgets or scale back activities if necessary. “We are hopeful that [extended learning time] will be funded,” Honoroff said.

A Manhattan principal, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said it was a relief to be out from some of the pressures of the Renewal program, which included lots of extra mandates that didn’t feel directly connected to improving instruction.

This principal said there were repeated requests to fill out paperwork offering a “root cause analysis” of everything from low test scores to attendance issues. “It would eat a day of my life,” the principal said. “Then I would never see it ever again.”

Still, there are downsides to being on the outside of the city’s improvement efforts. Teachers at the same school received training from Teachers College to improve writing instruction, which the principal linked to gains in student performance. But it’s unlikely, the principal said, that the school will continue the training for new teachers without the financial support of Renewal given other competing demands on the school’s budget.

Uncertainty about the next phase of school improvement isn’t limited to principals: Even borough-level staff members responsible for working directly with schools said there has not yet been clear guidance.

“There’s a lot less structure for the work,” said one staffer who works directly with schools, and spoke on condition of anonymity because the person was not authorized to speak publicly. “The criticism of Renewal is that it was too targeted, too specific, too top down,” the staffer said. But with the new framework, “You’re kind of left with, ‘What does this look like?’”

The borough-level staffer said they have been asked to focus on schools designated in January as low-performing by the state, first by helping them conduct annual comprehensive education plans required of every school.

City officials said they have “revamped” this planning process, which will help determine what kinds of help schools receive, and now includes “quarterly checkpoints” on how schools are progressing on individual goals including test scores, graduation information, and rates of chronic absenteeism. A spokeswoman added that superintendents and borough office members will reveal more about what help schools can expect at a back-to-school event in August.

“We have been working for months to revamp existing systems and develop new ones that will allow us to provide tailored support for every school, and we’re excited to hit the ground running in September,” education department spokeswoman Miranda Barbot said in a statement.

Mark Cannizzaro, head of the city’s principal union said it could be difficult for school leaders to move at full-steam next year given that they don’t yet know exactly what kinds of help they will receive and haven’t had time to communicate plans to educators across the school.

“Things that are going to be rolled out [next] school year are not going to have any opportunity to take root until the following school year,” he said.

Adding to some of the uncertainty about the next phase of school improvement, Abram Jimenez, whom Carranza hired to help oversee school improvement efforts, resigned after the New York Post reported on elements of his employment history, including that he left from a previous school after a probe into misused school money. The Post reported that there was not a competitive process for his hiring; a spokeswoman for the city’s Special Commissioner of Investigation confirmed that they have opened an investigation into Jimenez.

A department spokeswoman emphasized that the chancellor’s school improvement efforts weren’t solely assigned to Jimenez, and that senior officials including deputy chancellors and executive superintendents are also spearheading the effort. Officials said Cheryl Watson-Harris, Carranza’s second-in-command, will oversee much of Jimenez’s school improvement portfolio.

A spokeswoman added that the department plans to hire a “chief strategy officer” under Watson-Harris, who will take over Jimenez’s efforts to launch a new data system called EduStat. That system will give senior department leaders up-to-date information about school performance, partly so they can figure out which schools need extra training, coaches, or other services throughout the year.

Still, big questions remain: Unlike the Renewal program, top officials have declined to offer any details about how much money will be devoted to their improvement efforts, or even the criteria they will use to determine whether the investment is paying off.

Priscilla Wohlstetter, a Teachers College professor who has studied school improvement, said there are advantages to a strategy that is less rigid because there aren’t many surefire methods to quickly turn around schools.

But, she added, the lack of details about elements of the department’s latest improvement efforts could reflect an unwillingness to face accountability if the results are disappointing — especially after the mayor took political hits for the Renewal program’s shortcomings.

If they offer specific benchmarks, “they’re going to be held accountable for it,” she said. “They’re not ready for that.”