New York City students applying to high school next year will encounter a new system with waitlists instead of a second round, the first significant change to high school admissions in 16 years.

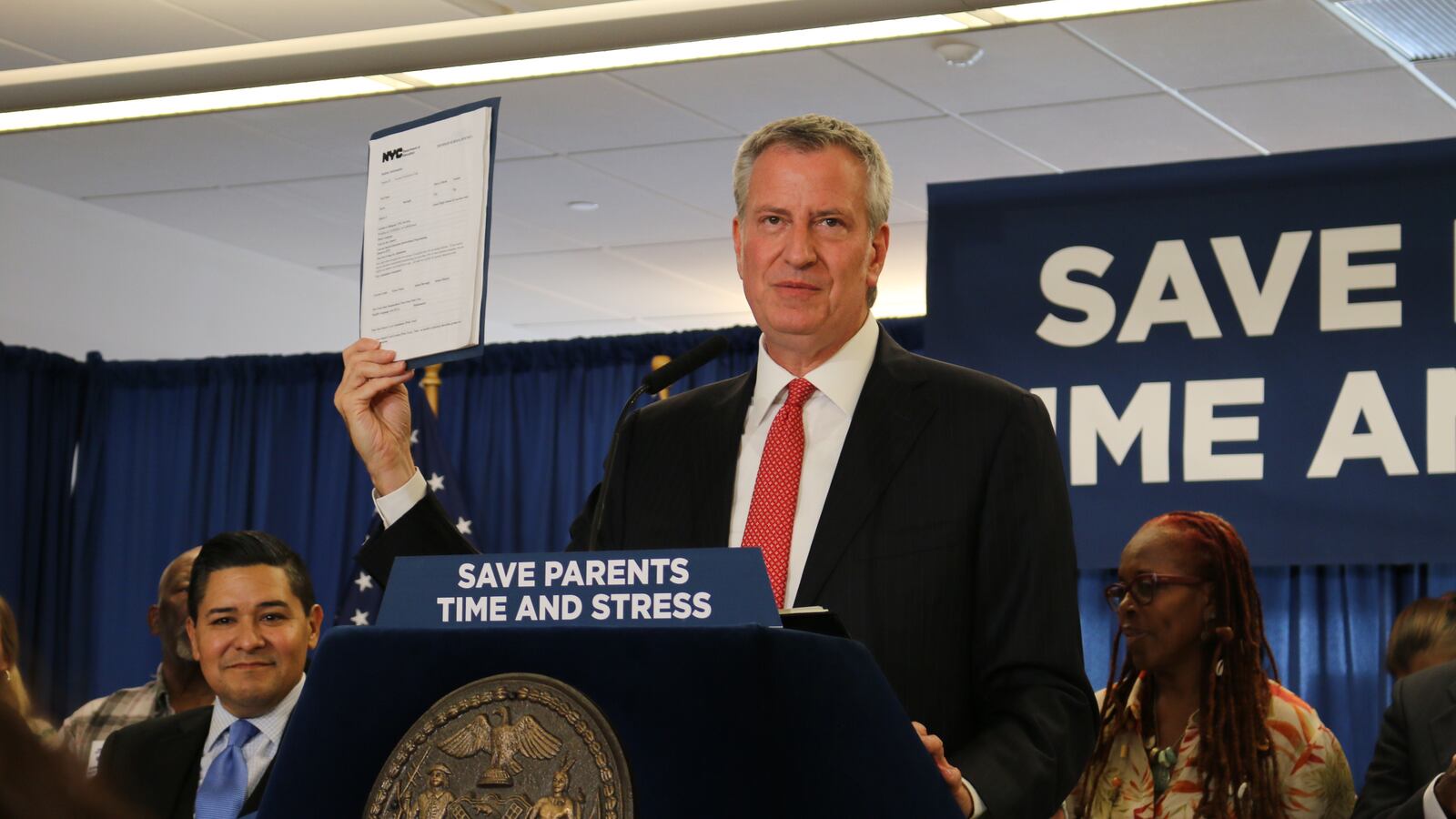

Mayor Bill de Blasio said the overhaul is meant to streamline admissions, but it’s far from clear whether the changes will have the intended effect.

“It’s actually going to be simple to apply to schools for your kids for the first time in a long time,” de Blasio said, standing at a podium emblazoned with the words “Save Parents Time and Stress.” “Obviously these are things that should have been done a long time ago.”

Starting next year, the city will allow students to sit on waiting lists for schools they wanted to attend, but didn’t get into. The city is also eliminating the second round of admissions, which it now uses to for students who aren’t matched to a school they applied to during the typical process.

It’s unlikely the changes will make the application process less burdensome, as de Blasio suggested. The crux of the admissions system will remain the same, requiring families to invest time and resources into researching and applying for schools in a process that is often difficult to track.

Now, thousands of students will be placed on waitlists that didn’t previously exist, leaving families to wonder through September whether they’ll get a more desirable assignment. Last year, only 34,000 students received their top school pick — meaning another 44,000 would have ended up on at least one waitlist.

Though the city and mayor are under heightened pressure to address persistent school segregation, which many say is fueled by the complicated admissions process, the changes aren’t designed to alter those patterns. New York City schools are among the most segregated in the country but de Blasio has been reluctant to make systemic changes, largely leaving integration efforts up to motivated local communities.

What’s changing: New waiting lists for schools

In New York City, students must apply to high school, a rite of passage for nearly 80,000 students a year. Students list up to 12 schools they want to attend, and a complicated algorithm matches each student with a single high school. (Students can also be accepted to one of the city’s specialized high schools, like Stuyvesant, outside of this process.)

That algorithm is not changing. But until now, a student matched with his third-choice school, for example, would simply have been assigned there. Now, the student will be assigned to that third-choice school, but also put on a waiting list for their first and second choices. Students can also add themselves to additional waitlists, even among schools they didn’t list on their initial application.

The city says students will be told their place on each waiting list and can track updates in real time. Students on waitlists will be offered seats as soon as they become available. Still, a spokesman said, “We don’t expect a dramatic increase in students getting a higher choice” as a result of the waitlist process.

“It’s like going to a store and getting the ticket, you know what number you are, and you know how many folks are ahead of you, and you’ll be able to watch the process go,” said Deputy Chancellor Josh Wallack. “You’ll also be able to talk with an administrator in a school who can give you a sense of how much waitlists move each year and that varies a bit by school.”

City officials said they would provide training to school officials to help them manage their waitlists, suggesting that schools will have new authority over the admissions process. That’s likely to raise concerns about whether savvy families will be able to influence their place on that list, or their movement off of it.

Other big questions remain about how this will work. How much oversight will there be regarding how students are called off of the waitlists? Will in-demand schools receive any extra support for managing those lists? When, exactly, will those waitlists close?

One Brooklyn high school principal said students moving off of waiting lists could create a domino effect, making it harder to create student schedules or finalize the budget.

“It’s definitely extra work for the schools, but to me it’s more about the uncertainty of knowing that any kid who’s on your roster might just disappear to another school at any time because they got in somewhere else,” said the principal, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Robin Broshi, a parent on the Community Education Council in Manhattan’s District 2, said knowing your child’s rank on a waiting list brings more transparency to an opaque process. Still, the changes will not do much to make the system easier to understand or more fair, she said.

“To me, this is a logical way this should work,” she said. “We’ve gone from really cumbersome, to a little less cumbersome.”

What’s changing: No second round of admissions

The other big shift will be what happens to students who aren’t matched to a school they listed on their application.

For years, students who didn’t receive a match — because they listed few schools on their application, didn’t meet the entrance criteria for their choices, or the schools they applied to were simply oversubscribed — would enter a second application round. That allowed the students to rank schools again, choosing among those with open seats.

This year, the city began assigning those unmatched students to a school, while still allowing the students to enter a second round. Now, the city is eliminating round two altogether — a move that may be welcomed by schools that dedicated staff time to information fairs.

“It will make principals’ in schools jobs easier because they will no longer have to do recruitment for the second round,” said John Wenk, former longtime principal of Lower Manhattan Arts Academy. “Going back to the recruiting fairs is a pain in the butt.”

Families “will be able to access in-person support at Family Welcome Centers, rather than wait to participate in a second process,” the city said in a statement.

Doing away with the additional admissions round could also save families time by eliminating the need to explore other options. But that process affected relatively few families. Laura Zingmond, an editor with the review site Insideschools, said only about 7% of students weren’t matched to a school they chose every year.

On the other hand, the second round gave families more choices about where to apply — a process that now will now go away.

Some principals said doing away with the second round of admissions could complicate their efforts to recruit families who may not have initially considered them.

“We think it’s a time to shine because they’re looking beyond their first choices — they’re looking at the schools with the less established reputations,” said an administrator who oversees a grade 6-12 school in Brooklyn that typically does not fill all of its open seats. “I would want to read through the details to find out: Where’s our chance to fight for those kids?”

What’s changing: Middle and elementary school admissions

In middle and elementary school, parents will also be able to see and track their position on school waiting lists online.

What’s not changing

The admissions timeline will be unchanged, the city says, with applications opening in October, a December submission deadlines, and offers sent in March.

Reema Amin contributed to this report.