At home, fifth-grader Aileen Shao usually speaks Mandarin with her family. So when she heads to the hallways of P.S. 1 in Brooklyn for summer school, she helps her classmates connect to one another.

“Most of the time I need to translate for my friends,” Shao said of her peers who speak Mandarin and want to talk with students who are also learning English.

Shao is among the roughly 7,500 New York City children who attended free summer programs that are designed to help multilingual students — children who are learning English as a new language — build skills in core subjects, such as math, while developing their language skills. Depending on the program, there’s also lighter summer fare, such as field trips and cooking classes.

Students can lose their grasp of a new language over the summer because they might only be speaking it in a limited capacity, if at all, educators say. There’s not a lot of research around summer learning loss among English language learners, but one 2012 study found that students from non-English speaking homes experienced a bigger loss of English vocabulary while school was out compared to students from homes where English is spoken.

Even as the city has added new programs, the demand continues to grow. Compared to last year, about 1,000 additional students took part this summer as the city added options for current first-graders, an education department spokeswoman said. Still, some school leaders who tout the program’s benefits would like to see the program expanded further in years to come.

While New York City has mandated summer programs for students it identified as being at risk of falling behind, the program Shao attends is voluntary. Families can choose to send their children to one of the city’s 99 summer programs for English learners.

Getting the word out about free programs can be challenging in immigrant communities. For some parents, a language barrier keeps them from understanding the promotional materials and, for others, there’s a distrust of who’s actually running the show. But P.S. 1’s principal, Arlene Ramos said she has the opposite problem, noting, “The challenge is not having enough classes to offer.”

The demand was so high at P.S. 1, which welcomed students who attend four schools in the neighborhood, that they doubled the number of seats for first through fifth-grade classes. That program served a total of about 200 students, which still left about 60 to 70 families on the waitlist, Ramos said.

The education department added 11 multilingual learner summer programs this year and for the first time offered seats for first-graders, according to Danielle Filson, an education department spokeswoman.

Waitlists are managed at each school so it’s not clear how many of the nearly 100 programs were oversubscribed. The department said it works with schools to monitor demand. Multilingual learners in K-8 can choose to attend any program in their district, and a spokeswoman said they had enough seats to meet the demand citywide this year. But some families may not want to travel beyond their neighborhood to where there were open seats.

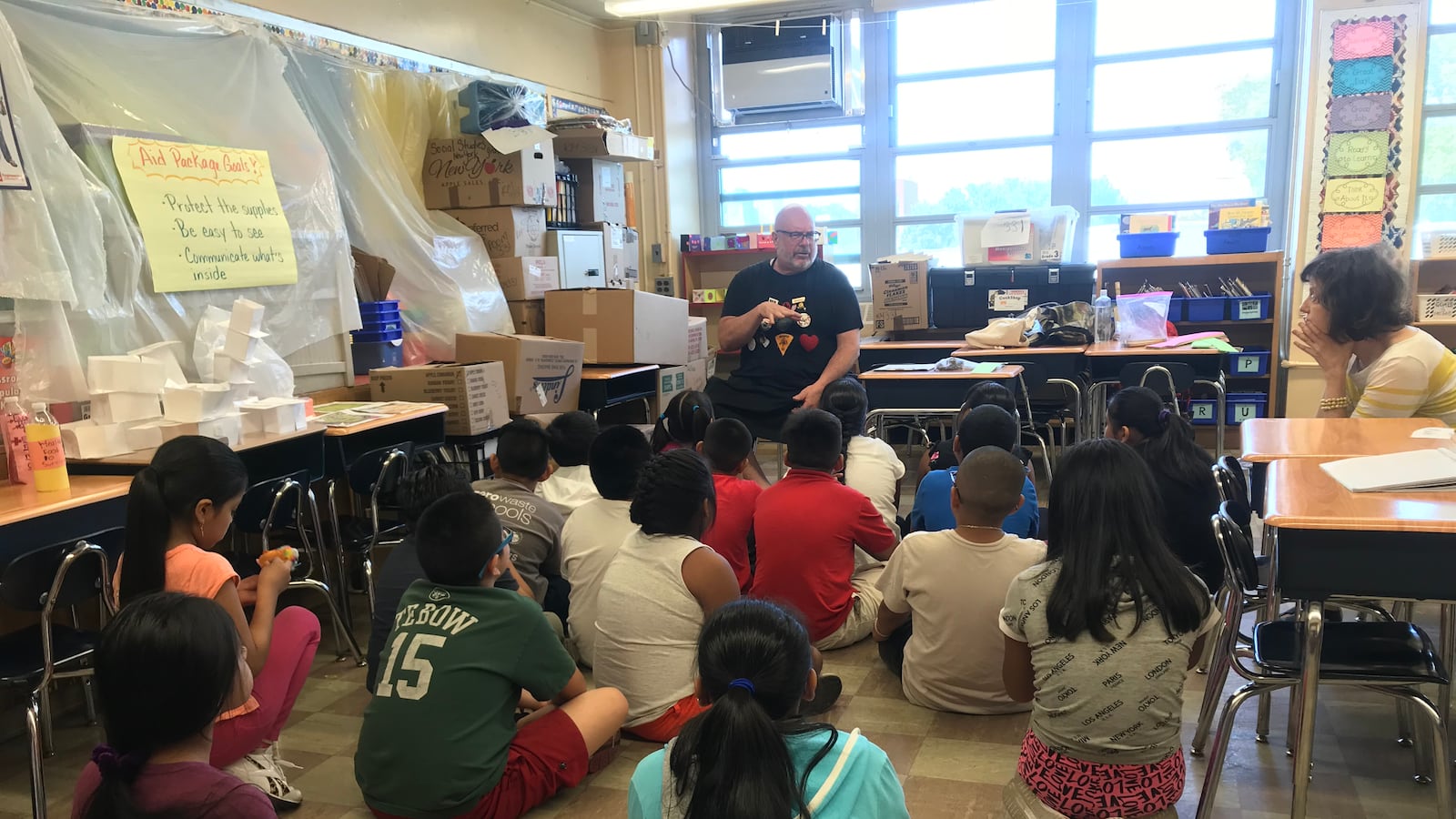

At P.S.1’s program — during the school year, the student population is 43 percent multilingual — there are STEM classes like the one Shao was in, a popular cooking class called “Small Bites,” and an arts course.

Students also go on multiple field trips, including one to the Prospect Park Zoo. One of the goals of these off-sites: to encourage English use in social, out-of-school settings.

When students talk about the program, their grasp of English is not top-of-mind. Instead, like other 9-year-olds, they discuss their initial nervousness about meeting students from different schools, say, or how much fun they are having in their cooking class.

Olga Islas, who like Shao is a fifth-grade English language learner, was looking forward to more math lessons. “I was excited because I knew I’ll learn more,” Islas said, while taking a quick break from her STEM lesson.

But the language benefits are real and noticeable when the school year starts, said Jessica Knudson, principal of P.S. 516, one of the schools whose students attend P.S. 1’s program. She and Ramos are hoping the school can offer even more seats next summer, noting that it’s apparent that “parents really want these programs.”

“Being able to offer this to all our language learners would be wonderful,” Knudson said.