More New York City students in grades 3 to 8 passed their state exams this year than last, slightly edging out students statewide on English tests but lagging just behind in math scores, according to results released Thursday.

In New York City, 47.4% of students scored proficient in reading, compared to 46.7% last year, while 45.6% passed math, compared to 42.7% last year. City students again significantly outperformed New York’s four other big districts of Buffalo, Syracuse, Rochester, and Yonkers.

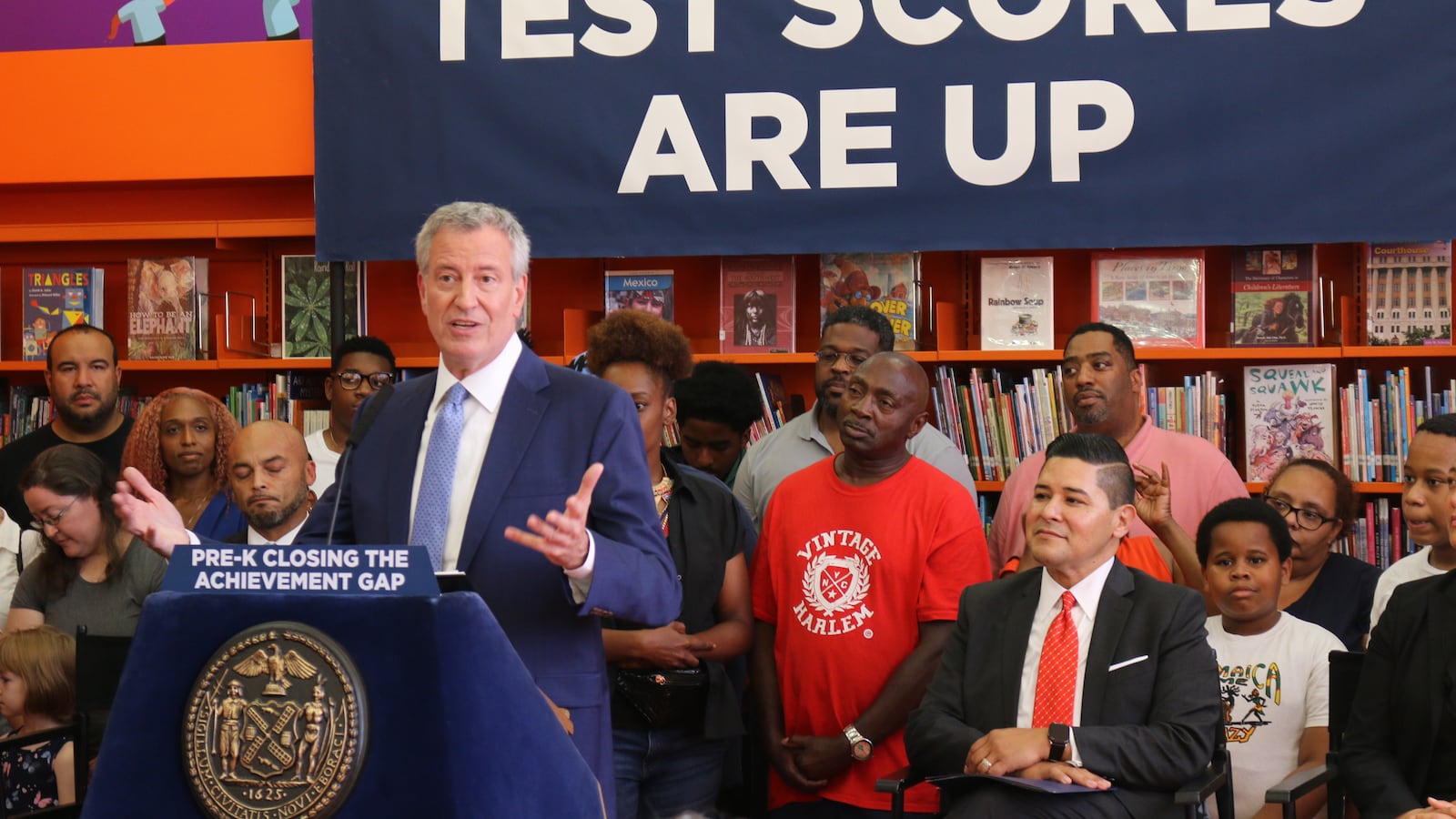

This year’s results are notable because they reflect the test scores for the inaugural class of students enrolled in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s universal pre-K program, and provide a glimpse into how Chancellor Richard Carranza’s first full year of leadership is impacting learning. This year’s scores are the first since 2017 that year-over-year comparisons can be made, since changes to the tests in previous years made such comparisons unreliable.

But disparities stubbornly persisted: 35% of the city’s black students passed reading exams, and 28.3% were proficient in math. For Hispanic students, 36.5% were proficient in reading and 33.2% passed their math exams.

On the other hand, 66.6% of white students passed reading exams, and the same percentage passed math.

“Troubling gaps persist,” state Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia told reporters. “Though we’re on the path, our goal of equity has not been achieved.”

Just 9.3% and 18.9% of children learning English as a new language passed their reading exams and math exams, respectively, far below their English-speaking peers. For students who have ever been classified as English language learners — known as “Ever ELLs” – 59.3% scored proficient on English exams and more than 61% earned passing math scores. About 16% of students with disabilities were proficient in English, and 17.5% were in math.

Changing political winds in New York have swept in more opposition to using standardized tests to hold schools and teachers accountable. Even so, the assessments still carry weight. The state adopted a new plan, based on federal education law, on how it grades individual schools, and test scores still have significant influence on whether they’re labeled struggling. A state law passed this year no longer requires school districts to consider state test scores when evaluating teachers, but those districts can still choose to include them or swap them out for other assessments, subject to collective bargaining.

New York City has already moved away from using the tests to evaluate teachers. But a lot of nervousness revolves around admissions — the city’s most competitive middle and high schools consider students’ scores when deciding who should get a seat.

Initial reactions to this year’s results were muted, perhaps a reflection of the state’s complicated relationship with testing.

“Assessments are a part of the larger picture that we look at when we examine performance levels across the state. This year’s test scores are a positive sign that we are making progress,” Elia said in a statement.

This year’s third-grade test-takers include students from the first expansion wave of the mayor’s signature universal pre-K program, which offered free pre-K to 33,000 more children at the time. Last year, de Blasio signaled that 2019 test scores could be an early indicator of how well pre-K is preparing students for the future, while acknowledging that multiple measures should be examined.

Compared to 2018, the share of third-graders passing reading exams went up more than 3 percentage points this year, and math scores stayed relatively flat, inching up just one percentage point. Those gains were comparable from 2016 to 2017, when 2% more third-graders passed the reading and math exams (2017 was the last time state test scores could be compared year-over-year).

It’s not clear, though, how many third graders who took state tests were also part of the first class of universal pre-K.

New York parents continued to be concerned this year over how state education officials would use test refusals when using a new framework to identify struggling schools. The number of test refusals is not the only factor officials use, but Carranza asserted this year that two city schools were labeled struggling because of how many families opted their students out of exams, which state officials disputed.

Statewide, the percentage of test refusals dipped two percentage points to 16%. The share of New York City students opting out was significantly lower than that: 7.6% and 8.3% refused English and math tests, respectively.

Charter schools in New York City continued to outperform district-run schools. In reading, 57.3% of students in charters were rated proficient, and in math, 63.2% passed.