Back in 2015, when DUMBO parents were making news for opposing a plan to change the zone lines for a local school, Max Freedman was a relative newcomer to another Brooklyn neighborhood undergoing rapid change.

A resident of Bedford-Stuyvesant who was eyeing a career in urban planning, Freedman was intrigued by the issues of race and class wrapped up in the divisive rezoning debate. So he went to a public hearing about the proposed changes.

“I saw a postcard from the future of Bed-Stuy,” he recalled recently. “I wanted to look at where Bed-Stuy is now and see those pieces moving into place, to see whether we can be in public dialogue before there is a crisis.”

So Freedman turned to the Brooklyn Movement Center, a community organizing group aimed at empowering black residents of Central Brooklyn, where he connected with the group’s executive director, Mark Winston Griffith.

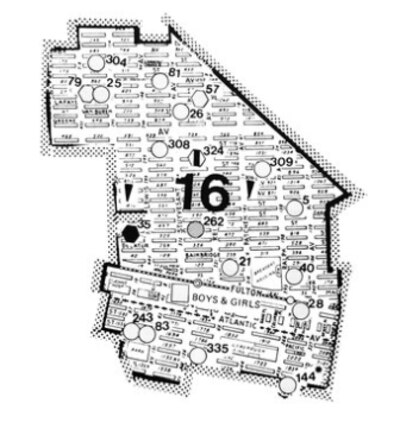

At the time, Griffith was working through what to do with the center’s 2013 report about the challenges facing the area’s schools. District 16 had become known for its segregated, struggling schools. The report had urged involving local families, educators, and community groups in an effort to turn them around.

“So much was wrapped up in history, but parents were not involved, and there was no sense of organizational power among parents,” Griffith said. “It was really striking at a moment when white parents were reconsidering coming into the neighborhood.”

Four years later, Freedman and Griffith’s collaboration has yielded an eight-part podcast series, “School Colors,” that looks at the past, present, and future of schools in District 16. The first installment of this Brooklyn Deep podcast series launches Sept. 20, and the second episode, out on Sept. 27, offers a fresh look at the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville conflict over community control that led to a citywide teacher strike and ultimately reshaped the school system.

Later, the podcast will take on what happened in the district after the city’s schools shifted to mayoral control, the complicated role of charter schools in the neighborhood and, finally, the issues presented by the current wave of affluent, often white families moving to the area. The Brooklyn Movement Center will host a discussion group, and Chalkbeat will update you when new episodes drop.

We spoke with Freedman and Griffith about what they learned reporting the podcast, what they hope readers will take away, and how they think School Colors can inform the mounting debate about integration New York City schools. Here’s the interview, condensed and edited for clarity.

How did you come to tackle this topic on a podcast together? And why this podcast about District 16 now?

Freedman: I moved to Bed-Stuy in 2012. I looked around and I thought, “Something’s happening here and I don’t understand it, but I am a part of it.’ I knew I wanted to do work in a community where I live and in partnership with an organization that was already established. That brought me to the Brooklyn Movement Center.

Griffith: The Brooklyn Movement Center is a black-led, direct-action community organizing group, working against the backdrop of gentrification, neighborhood change, displacement — these are themes in our work. [In our 2013 report], we found striking things: This district which was predominantly black was severely underenrolled, it was not a cohesive district, everyone was doing their own thing. So much was wrapped up in history, but parents were not involved, and there was no sense of organization power among parents. It was really striking at a moment when white parents were reconsidering coming into the neighborhood.

Freedman: I went to a public hearing [about the DUMBO rezoning]. It was very clear to me that the [city] was prepared for there to be pushback from wealthier families … but that they were not prepared for pushback from parents from the underenrolled school, who actually were not thrilled … even though it would mean the school would be quote-unquote integrated.

Whatever you want to say about gentrification — the good, the bad and the ugly — it certainly makes people feel like they don’t have any power to determine the direction of their community. And it often comes from ideology that says there was nothing good here before. There’s a lot of pride in this place and a rich history of parent power. We wanted to find out: Where did that go and what does it mean now that parents are trying to change that, from a few different directions?

The series takes listeners to the present day and into recent conversations about whether and how District 16 schools should be racially integrated. How would you say the podcast will be relevant to the renewed debate over segregation and the recommendations the city recently received about how to reduce it?

Griffith: We’re very aware of the timing of this podcast. It’s coming at a moment when integration and desegregation are coming to the fore. These issues have been simmering for a while. We have felt them as an organization. I have felt them personally. As a parent who lives in District 17 whose kids went to school in District 15, constantly having to navigate the racial dynamics of these districts, it was clear to me that New York had a racial problem in its schools. We see these battlefronts opening up in different places.

Part of the point of the podcast is to say we didn’t land here out of nowhere — that these issues have been going back decades or even centuries. We want to give people a better understanding of how points of view have evolved — and calcified, in some ways.

We want this not only to be something to listen to but also to sit down and talk about. How do we navigate this moment we’re in right now?

Freedman: Since we started doing this work the way we talk about integration in this city has evolved considerably. For most of history the conversation has revolved around the feelings of white people: A lot of the conversation is, ‘We can’t do this, white people and people with money will run away. And then the schools will be more segregated, not less.’ So much of our policy-making is based on the fear that people with money will take their money out. It’s not 1975 anymore. Part of the focus was to reorient the conversation about school integration — to look through the perspective of nonwhite people.

One of the main characters is the president of the [Community Education Council] for District 16 NeQuan McLean. One of the great things about doing this over a long period of time is that we’ve been able to see people evolve. In 2017, he said, integration is not the concern — we’re thinking about school quality. But he became a member of the School Diversity Advisory Group and now believes that G&T, which he fought to come back [to the district] under Bloomberg, is a problem and now is on board with these recommendations [to phase out gifted programs]. To have a voice from District 16 at the center of the conversation at all is dramatic, because this is a district that was forgotten for many years. Then to have him evolve on this issue … We’re very much in conversation with the recent developments.

Griffith: What’s hitting the headlines is being told through policy conversations. And I think that one of the things we want to do through the podcast is to make those policy conversations more human. If you live in New York or anywhere in this country, if you’re a parent, if you have had to confront issues of race, if you’re a breathing human being, it’s going to be hard to not hear yourself or identify with any of the struggles you’re going to hear about. We’re trying to help people make connections between what they’re feeling every day to the policy debates.

What do you think New Yorkers need to know about the history of schools in District 16? And what will listeners who already know a lot about the history of schools in New York City learn by listening?

Freedman: You can’t understand what happens now in the city without understanding Ocean Hill-Brownsville. It’s something people are afraid to talk about. So we’re going to talk about it.

Griffith: It ripped people apart. … It’s a part of history that I don’t think people are entirely prepared to own up to or be accountable for. It also integrates this tension between integration and self-determination, which is something that we want to deal with head on.

Freedman: I don’t think it’s a totally new version: Charlie Isaacs, a JHS 271 teacher who published a memoir about his experiences five years ago, had a big impact on how we shaped the story. But we also interviewed kids who were students at JHS 271 at the time whose voices haven’t been heard before. And there was a short version in “Eyes on the Prize” [a late-1980s miniseries about the Civil Rights Movement] — we licensed the original interviews, so tape that has never before been heard from them will be heard in the podcast.

Griffith: Everyone has a perspective and so do we. We’re trying to tell it in a way that will be fresh in the ways Max described, and centering it in the conversation about where we are today. You don’t hear much that traces community control, decentralization, mayoral control, to where we are today. That, I think, will be new.

Freedman: We focused on the community. That’s not to say we don’t talk to the teachers or to the union, but that’s our orientation. We want to talk about the aspirations of this community, and what they achieved. That’s really what gets lost: what they achieved, which was a lot.

Griffith: I’m a 56-year-old black man. Max is a 31-year-old white, Jewish guy. We found our own connections. My uncle was a teacher and later a principal …

Freedman: And my mom’s cousin was a teacher in Brooklyn and he was on the other side of the picket line.

Griffith: We infuse our personal stories that make the narrative so much richer.

What was most surprising to you during the reporting process? Any moments where you laughed or cried? Or a story from the reporting process that could get readers excited to listen?

Griffith: When we go back literally 150 years or go back 50 years, it sounds like you’re talking about 2019. That’ ‘s what we didn’t fully anticipate, and there’s so much drama, that we’ve discovered here, not just in the history but in what’s happening today. The characters — well, we’re not saying characters — they are 3-D people who exude all of this humanity, who are really striking and interesting people that people are going to be fascinated to listen to.

Freedman: What we did find here in the present is a lot of people trying to do the right thing and butting heads in the process. Here’s one example: Later in the series, we’re going to talk about the conflict on the PTA at one particular school. Every single person we talked to about it started crying or very nearly started crying — and it happened three years ago! It was incredibly emotional. We’re sitting on top of this deep and rich and complicated history of this country and it manifests as drama on a PTA.

Griffith: We were struck by the extent to which this is centered on schools and issues of gentrification, yet the extent to which these institutions are proxies for much broader issues that go far beyond education and in some cases have very little to do with what’s happening in the classroom. It is about the children but it’s not at the same time.

Freedman: Teachers might be frustrated listening to it, honestly. We’re talking very little about instruction or pedagogy.

Griffith: Hopefully we’re creating the context for some kind of policy change, but we’re almost at the end here but some of that is still evolving. I thought we would have been closer to solutions that we actually are.

Freedman: My naive hope is that listening to this will help people have dialogue across difference.

Griffith: None of us sees ourselves in the business of conflict resolution. Still there is some level of hope and expectation that listening — this is going to sound mad hokey — you are going to see the humanity in people you didn’t see the humanity in before. It could be a potential big gift to people in this neighborhood and this city and this country.